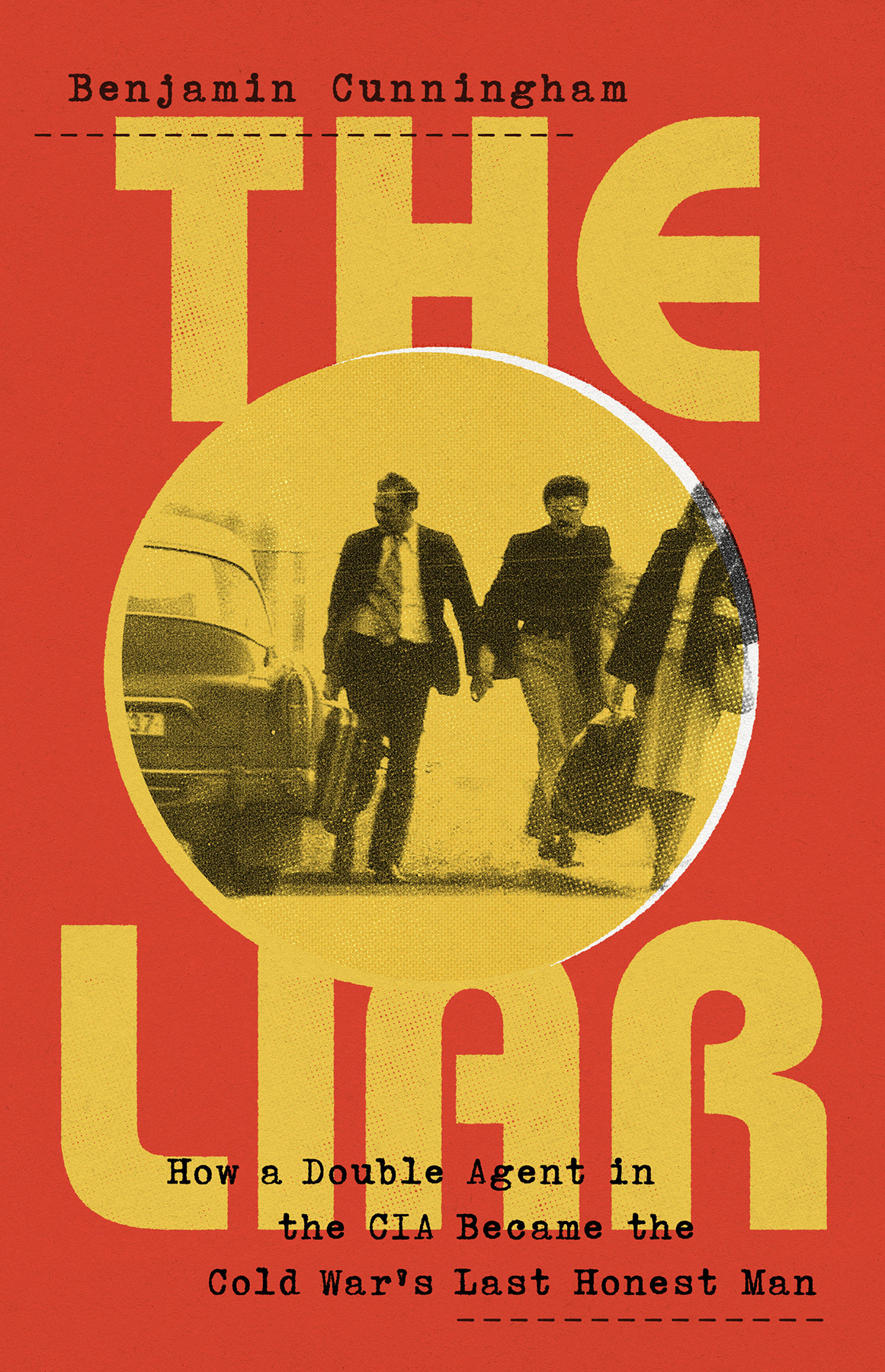

Copyright 2022 by Benjamin Cunningham

Cover design by Pete Garceau

Cover image from Security Services Archives

Cover copyright 2022 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

PublicAffairs

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

www.publicaffairsbooks.com

@Public_Affairs

First Edition: August 2022

Published by PublicAffairs, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The PublicAffairs name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022937759

ISBNs: 9781541700796 (hardcover), 9781541700819 (ebook)

E3-20220720-JV-NF-ORI

To Bibi, for meeting me halfway

A man who lies to himself, and believes his own lies becomes unable to recognize truth, either in himself or in anyone else, and he ends up losing respect for himself and others. When he has no respect for anyone, he can no longer love, and in him, he yields to his impulses, indulges in the lowest form of pleasure, and behaves in the end like an animal in satisfying his vices. And it all comes from lyingto others and to yourself.

F YODOR D OSTOYEVSKY

This is a true story. Names, places, and incidents are real. Some of the interpretation is my own.

Quotations from secondary sources are cited in endnotes, and the texts are compiled in the bibliography. Quotations that do not come with a specific citation either came from interviews (also listed in the bibliography) or from archival documents from the Czech Republics State Security Archives.

Quotations from those archival documents are translated into English, but the original material consisted generally of Czech (occasionally Slovak, and very occasionally German or Russian) language documents. On occasion, juggling multiple languages presented some special challenges.

For example, the dialogue that appears in the prologue originally occurred in a variety of languages. There are, amazingly, actual audio recordings of this encounter. However, much of thisas might be expected of reel-to-reel recording tape stored with little care by the Communist regimeis of low quality. There are transcripts of the discussion translated into Czech. I reviewed both, but the dialogue presented here comes primarily from Czech transcripts translated into English. They were, by necessity, edited for context and clarity but with every intention of keeping the original meaning intact. Other similar small challenges arose throughout the writing process.

In my view, a good many Cold War stories fall into lazy binary narratives, and twentieth-century history is often projected through caricatures of famous people. This book does its best to avoid both.

Heroes dont exist, only cattle for the slaughter and the butchers in the general staffs.

J AROSLAV H AEK

SEPTEMBER 10, 1976

tykoly, Czechoslovakia

About twenty miles outside Prague, in a riverside village of little distinction, Karel finds himself in a room with dull walls and a cold, dead fireplace. He doesnt know why he is there.

The unexceptional-looking house sits empty most of the time, but the neighbors tend to stay away anyway. Occasionally they see people milling about the cottage; the black government-issued Tatra 603s parked outside signal they arent up to anything good. Best to go the long way around when walking the dog or heading out for a beer. Across the river, theres a pub with outdoor tables. Like something out of Greek mythology, a boatman with a pole can take you across.

The cool and breezy September day offers a welcome respite from New Yorks scalding August. But as Karel smooths the collar on his Brooks Brothers jacket, it strikes him that he hasnt seen his passport since they crossed the border. That cannot be good.

Karel is making small talk when another well-dressed man enters the room. His suit is darknot exactly stylish, but well cut, tie in a full Windsor knot. Old-fashioned looking, to be sure, but clean, serious. No doubt official. The mans receding hair is slicked back with pomade. Like Karel, he looks to be in his early fortiesprodigiously young for a KGB general. His name is Oleg Kalugin. He is a spy, and hes arrived to interrogate another spy.

Sorry I am late; do you speak Russian? Kalugin asks as he enters the room.

I understand it fine, but I dont speak all that well, Karel says. In America, theres no one to speak Russian with.

Kalugin stops on Karels side of the table and turns to look him in the face. Karel Koecher stays seated but sizes up Kalugins thick silhouette framed in the light of an open window. Karel doesnt know it, but Kalugin has defied Moscow Center orders to be here today. As far as KGB chief Yuri Andropov is concerned, Czechoslovak intelligence is conducting this interview on their own.

Standing up straight, chest out, looking confidentcocky, evenKalugin gives no impression hes worried about the consequences of his insubordination. In fact, it stands to reason that Kalugin has his own reasons for being there, but they are not obvious, and he does not reveal them.

Like Karel, Kalugin is fluent in a gaggle of languages. As he continues in English, his nondescript patrician lilt sounds a bit like Cary Grantbut heavy, pedantic, and stripped of bounce. Kalugin pulls a chair from the table, rotates it to face Karel, takes a seat, and begins a stiff greeting that answers a few questions before he raises a host of new ones.

I am glad to welcome you in the name of Soviet-Czechoslovakian friendship. I am a guest here on invitation of our Czechoslovak friends, and I have to say, as a representative of a friendly service and collaborator, I am glad to meet you, Kalugin says. I have heard and read a lot about you. And now I hope my company is going to be useful for clearing up the doubts we share, as well as our common interests. I have some questions related to your personal security. Because the top priority for us is always the success of our people, no matter where they work.

Karel looks over Kalugins shoulder again, to the open window. Its now drizzling outside. Karel adjusts his stainless-steel glasses. His light-gray suit with flared slacks and his vibrant extra-wide tie look alien amid the humorless monochromes. Kalugins eyes are captivated by the stripes on Karels tie, as if they havent seen color in a decade or so. A bunch of Philistines, Karel thinks as he turns his chair, brushing his fingers through his salt-and-pepper mustache. He makes eye contact with Kalugin but stays quiet.

I might be repeating some things because I came in late, Kalugin continues. Well, thats okay; hopefully its not going to be too unpleasant. How are you? How is your health?

Good, a wary Karel says. Lets see in the evening.