First published in Great Britain in 2021 by

Pen & Sword Military

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

Yorkshire Philadelphia

Copyright Adrian Greaves 2021

ISBN 978 1 39900 953 9

eISBN 978 1 39900 954 6

Mobi ISBN 978 1 39900 955 3

The right of Adrian Greaves to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Limited incorporates the imprints of Atlas, Archaeology, Aviation, Discovery, Family History, Fiction, History, Maritime, Military, Military Classics, Politics, Select, Transport, True Crime, Air World, Frontline Publishing, Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing, The Praetorian Press, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe Transport, Wharncliffe True Crime and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Or

PEN AND SWORD BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

E-mail:

Website: www.penandswordbooks.com

Introduction

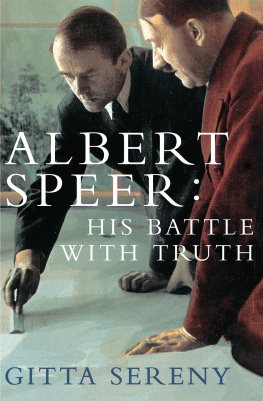

Meeting Albert Speer

More beguiling and dangerous than Hitler who had died before in the ruins of Berlin.

O n the night of 10 May 1941, Hitlers deputy, Rudolf Hess, made a remarkable solo flight from Augsburg in southern Germany to Scotland in a misguided personal attempt to seek peace between Germany and Britain. At the time, the German High Command was under serious pressure from having to fight on two fronts, the British in the west, the Russians to the east. Hesss logic was to arrange peace with Britain to enable German forces to be concentrated on the Russian Eastern Front. His flight was undertaken in complete secrecy and without the knowledge or authority of Hitler. In total darkness he parachuted from his plane leaving it to crash near Glasgow and on landing in a field he was immediately detained by local farmers pending the arrival of police. Within hours his true identity was revealed whereupon Churchill ordered that he was not to be pandered to, but to be deliberately treated as a prisoner of war. He was initially taken to the Tower of London then, for the duration of the war, he was held prisoner in Wales. Hitler declared Hess insane.

A year later, my recently married father-to-be, an officer in the Royal Artillery Regiment, was on a course in Wales before being posted to India; my mother worked as a typist in one of the government ministries in London. One weekend my father was unexpectedly detailed to command an escort that took Hess to Surrey, believed by my father for medical reasons. That weekend, my parents somehow managed to meet in London, and nine months later I was born in the middle of an air raid, I suppose, courtesy of Rudolf Hess.

Eighteen years later (1961), I was commissioned into the army and posted to the Welch Regiment then serving in West Berlin, a divided city more than 100 miles behind the then Iron Curtain dividing the Allied West Germany and the Soviet occupied East Germany. My arrival there coincided with the construction of the Berlin Wall and a seriously worsening Cold War situation. During the two exciting years that followed, I was regularly detailed as the duty guard commander at Spandau Prison which housed the three most senior surviving Second World War Nazi war criminals, Rudolf Hess, Baldur von Schirach and Albert Speer. All three had narrowly escaped execution on the gallows following their trials at the 1946 International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg and were part-way through long prison sentences. While performing this duty for the first time, a regular task for junior officers, and knowing of my fathers brief time escorting him, I hoped for a sight of Rudolf Hess. Instead I unexpectedly found myself standing next to Hess outside his cell in the prison corridor. As his flight to Scotland had brought about my very existence, and in very shaky German, I thanked him; he ignored me and walked away.

However, Albert Speer overheard my words and quietly asked for an explanation. Unsure of prison protocol I stepped back but the governor accompanying me indicated I could speak to Speer who then invited me to join him in the prison garden. Naturally I accepted, after all, Speer had been Hitlers longtime friend and Reich armaments minister. We had a friendly chat, the first of many such discreet but unofficial meetings. Thereafter I was regularly able to meet with him, and, with his full co-operation, and even enthusiasm, over the next two years we amicably discussed an array of subjects, including the delicate question of his and German guilt for war crimes. At his trial Speer had successfully protested his personal innocence of, or participation in, war crimes against humanity, but accepted vicarious responsibility having been a senior minister of Hitler, for which he was sentenced to twenty years imprisonment in Spandau. Our highly unofficial discussions were a remarkable opportunity for a young army officer to acquire a singular and in-depth insight into this influential mans memories of Hitler and of his thoughts during his fifteen years as a Nazi minister. Our conversations were especially unique because Speer was still serving his sentence and, apart from his co-defendants, Schirach and the delusional Hess, he was completely isolated from the outside world or any press media. Despite our disparate ages and rank differences, he clearly enjoyed our many conversations, which I noted at the time, and his attitude to me was always friendly and courteous, and he spoke excellent English. Conversely, neither Hess nor Schirach would ever speak with me.

Following his much publicized release from Spandau in 1966, I watched Speer manipulate the enthusiastic media to perpetuate and develop his original not me defence which had saved him from the Nuremberg gallows. This line of defence, and by sticking to his story, was necessary for him to re-establish himself among post-war Germans. By the time of his release, his fellow countrymen were steadily progressing towards international acceptance, from being a nation of shattered war-weary people to being desperately in need of a good German to help repair the terrible reputation of their deeply shamed country. Speer soon succeeded beyond all expectations and almost became an elder statesman, much respected in Germany and internationally, and sought out by the media and politicians who all treated him with reverence. But was Speer as innocent as he portrayed himself, or was he the master of the ultimate confidence trick?