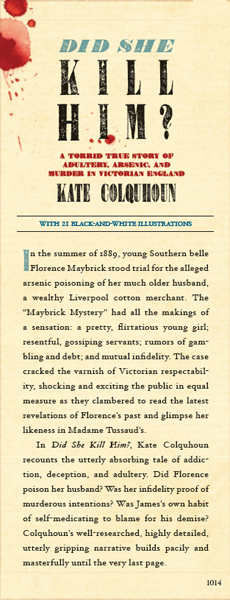

Also by Kate Colquhoun

available from The Overlook Press

Murder in the First-Class Carriage

This edition first published in hardcover in the United States in 2014 by

The Overlook Press, Peter Mayer Publishers, Inc.

141 Wooster Street

New York, NY 10012

www.overlookpress.com

For bulk and special sales, please contact ,

or write us at the above address.

Copyright 2014 by Kate Colquhoun

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast.

ISBN 978-1-4683-1034-4

it is too painful to think that she is a woman, with a womans destiny before her a woman spinning in young ignorance a light web of folly and vain hopes which may one day close round her and press upon her, a rancorous poisoned garment, changing all at once into a life of deep human anguish.

George Eliot, Adam Bede (1859)

I want a happiness without a hole in it The golden bowl the bowl without the crack.

Henry James, The Golden Bowl (1904)

The detail of this story and all italicised speech is taken from primary record, including Home Office documents, contemporary newspaper accounts, American archives, court transcripts and Florence Maybricks emotionally charged memoir.

I have chosen to quote sparingly from a number of letters written by Florence and printed in earlier books about the case despite the fact that the originals have since been lost; there is no reason to believe they were not accurately quoted and they give us rare glimpses into her state of mind. Endnotes indicate where this is the case.

Although I have stuck rigorously to contemporary sources, the reconstruction of history inevitably remains to some extent a work of imagination.

She had not expected them to be so quick and when the call came her pulse was still fast, her mouth dry.

She heard the key turn in the lock. Felt, rather than saw, the door swing open. Gathering her black skirts in one gloved hand and rising uncertainly from the wooden bench, she stepped out into the corridor, turning towards the stone staircase, ignoring the wardresss offer of support.

She can hear, now, the murmur of many voices from above, the shuffling of feet, throats being cleared. The very air seems to shiver with significance. Taking each step slowly, she fights to compose her features and to calm her breathing.

Five feet, three inches tall, alabaster pale beneath a fine black veil, the slender young widow has never seemed more fragile as she emerges into the open body of a packed courtroom. Turning through a hip-height gate to her right she enters the dock, taking her seat once again towards the railings at its front. Her small hands rest deliberately in her lap. Two female prison guards are close behind, one on either side.

She woke at dawn and it is now almost ten to four in the afternoon. The stooping judge re-enters through a door directly in front of her. She is the focus of the rooms attention as she looks up at him, her eyes fixed and unflinching. To Judge Stephens left a dark curtain ripples before being drawn to one side. Twelve black-coated men file into the jury box. It has taken them just forty-three minutes. She wonders whether any of them will dare to turn towards her. She is determined not to look away.

Dust motes dance in the light slanting from the windows before a cloud blots out the rays. Blown by a sharp wind, raindrops scatter against the glass skylight above her. There are seconds, then, of silence.

She hears the clerk ask his final question.

She straightens her back in the chair, feels the bare board beneath her feet, tries to raise her chin.

It is time.

Whenever the doorbell rings I feel ready to faint for fear it is someone coming to have an account paid.

The pen had hovered for a moment above the letter while she considered.

home at night she continued in her neat cursive script it is with fear and trembling that I look into his face to see whether anyone has been to the office about my bills.

*

In one of Liverpools best suburban addresses, was lost in thought as she sat in a silk-covered chair before the wide bay window. The parlour was almost perfect: embossed wallpapers offset red plush drapes lined with pale blue satin; several small tables, including one with negro supports, displayed shiny ornaments. A thick Persian carpet deadened the tread of restless feet.

A letter recently addressed to her mother in Paris lay beside her. It contained little of the chatter of the old days the reports of balls and dinners, of new dresses, of renewed acquaintances or the children. Instead, despite her effort to alight on a defiantly insouciant tone, it charted a newer reality of arguments, accusations and continuing financial anxiety.

In a while she would call Bessie to take it to the post. For the present her tapering fingers remained idle in the lap from which one of her three cats had lately jumped, bored by her failure to show it affection.

Today, the twenty-six-year-old was wonderfully put together, her clothes painstakingly considered if a little over-fussed. Loose curls, dark blonde with a hint of auburn, were bundled up at the back of her head and fashionably frizzed across her full forehead. Slim at the waist, wrists and ankles, but with softly voluptuous bust and hips, she was all sensuousness, with large blue-violet eyes that made her irresistibly charming and aroused in men. Yet a lack of angle in the line of her jaw conspired against Florence being a beauty, and a careful observer might even have noticed a peculiar detachment about her, for the young American was impressionable and egotistical, worldly but not wise.

Her glance lingered on the Viennese clock on the mantelpiece and slid across the cool lustre of the pair of Canton porcelain vases. Through the broad archway, early spring blossoms had been gathered into cut-glass vases and set on the Collard & Collard piano. Further down was the dining room with its Turkey carpet, leather-seated Chippendale chairs and sturdy oak dining table spacious enough for forty guests.

Each of these formal public rooms opened on to a broad hall where double doors led to steps and a gravel sweep that snaked out towards substantial gates set into walls draped with ivy. At the back of the hall a dark-wood staircase rose to a half-landing where a stained-glass window scattered coloured drops of light about the walls and floors. A narrower set of stone steps went down to the flagged kitchen, servants dining room, scullery, pantry, china and coal stores and the washroom with its large copper tub.

The parlour fire smouldered. Occasionally a log resettled with a gentle plume of ash.

Outside, beyond lace-draped French windows, lawns reached down towards the river, covered by a layer of thick snow that muffled the memory of happier summers. A pair of peacocks high-stepped screaming at the cartwheeling flakes past shrubberies, flowerbeds and summerhouses, round a large pond and through the thickest drifts lumped over the long grass in the orchard. The chickens ruffled their feathers against the cold; in the kennels and stables the dogs and horses breathed white into the cold air. A fashionable three-seated phaeton was locked away in its shed, protected from the encroaching white.