Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

Copyright 2019 by Gerald C. Van Dusen

All rights reserved

First published 2019

ISBN 978.1.43966.698.2

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019935342

print edition ISBN 978.1.46714.201.4

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

Detroit is an iconic American city with a rich and storied past. When the final history of Detroit is written, whole chapters will be devoted to how the Motor City put the nation on wheels and how the Arsenal of Democracy helped win World War II. Yet another chapter will explore the citys rich musical heritage, including its contribution to twentieth-century popular music as the home of the Motown Sound.

If the history is to be comprehensive, it must include certain darker realities as well. Rioting at the Sojourner Truth Housing Project in 1942 on the citys northeast side, on the Belle Isle Bridge in 1943 and on Twelfth Street in 1967 reveal the depth of racial discrimination woven into the fabric of life for many residents of Detroit.

And, of course, there will be a chapter on Detroit filing for Chapter 9 bankruptcy in 2013, the largest such municipal filing in U.S. history both by debt ($18 billion to $20 billion) and by population (700,000-plus).

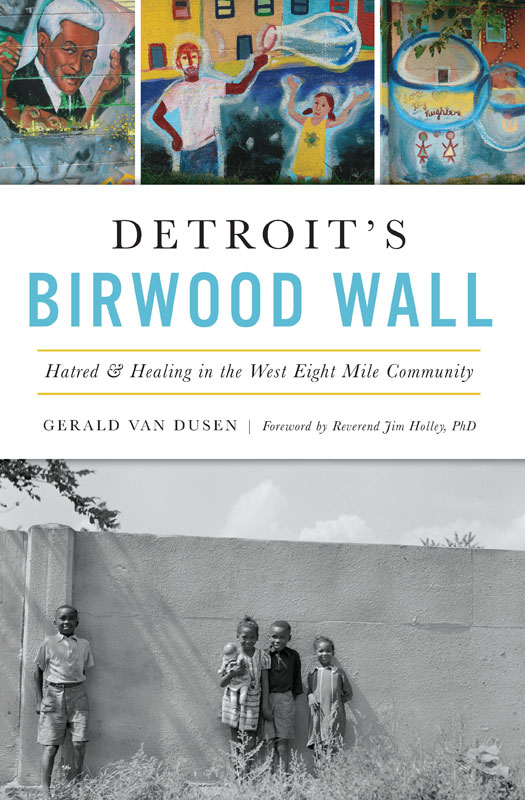

One chapter that needs to be included in any comprehensive account of Detroit would be the story of a small community in northwest Detroit that fought to overcome an egregious series of barriers, most dramatically symbolized by the infamous Birwood Wall, constructed in 1941 to even further isolate them from white Detroit.

The present volume, written ably and compassionately by Gerald Van Dusen, reveals perhaps for the first time how this isolated enclave of early settlers along Eight Mile Road chose the path of constructive engagement in the face of discrimination rather than the path of rioting and destruction.

Their story of overcoming obstacles is not over, for new and insidious barriers continue to be erected (think car insurance, banking and real estate redlining, as well as low broadband competition and deployment within communities of color and so forth).

Van Dusens book will make you think. And maybe it will help each of us step out of our tightly circumscribed localities and confront the bigger world.

REVEREND JIM HOLLEY, PHD

Senior Pastor

The Historic Little Rock Baptist Church

Detroit, Michigan

PREFACE

I learned of the Wall when I was sixteen years old. Although I grew up on the far west side of Detroit, I attended an all-boys parochial high school located on Seven Mile Road on Detroits northwest side. One day, a friend and classmate invited me to his house after school to work together on Latin and geometry homework. His house on Pinehurst was just a city block south of Eight Mile Road. After we finished our homework, we walked the neighborhood, and when we came across this long monolith of concrete on Mendota Street, my friend challenged me to scale the wall and walk its lengthwithout falling. I followed his lead, although I was not as adept as him negotiating obstacles such as overhanging tree branches and tall shrubs abutting the Wall. As we walked slowly, he informed me that he had walked atop the Wall several times, as it was a sort of neighborhood initiation. Kids had actually injured themselves falling and landing awkwardly. As luck would have it, just before we reached Norfolk, the first completed section of the Wall, I stumbled over a tree branch, fell into a backyard of soft grass and lay unhurt.

I recall asking my friend, Why exactly would anyone go to the time and expense of erecting such a formidable barrier to separate one neighborhood from another? Why not a simple chain link fence? My friend simply replied, It was built to keep people like me away from people like you. I dont remember anything else from that conversation or from that day, but Ive never forgotten my friends words.

A few years later, during the sweltering summer of 1967, I worked at a bank branch located in Detroits inner city. In late July, black residents of Twelfth Street rebelled openly and violently against pervasive police harassment and neighborhood neglect by city hall, leading to the most horrific weeklong loss of life and destruction of property in the citys history. Kathryn Bigelows evocative film Detroit chronicled but one aspect of the police brutality of the period. My bank manager notified each of us that it was business as usual, so we opened at 10:00 a.m. each morning of that week so that customers would have access to their accounts in those trying summer days. Customer after customer expressed the view that the violence and destruction of that week were only a matter of time. Overcrowding caused by an urban renewal policy that wiped out the large segregated neighborhoods of Detroits lower east side, Black Bottom, coupled by police harassment by a largely white police force that targeted young black males, had come home to roost.

I immediately thought of the various efforts to isolate and denigrate the black residents east of the Wall along Eight Mile Road, and I wondered how and why that section of the city escaped similar violence and rebellion. I had studied both the Sojourner Truth Riot of 1942 on the northeast side and the 1943 riot downtown in my Social Psychology class in college. But there was no mention in any of my texts or in any class discussion of the Birwood Wall or the community that the Wall was intended to isolate.

This book describes how the residents of a one-square-mile area of northwest Detroit adapted to life in relative isolation from the more affluent, white neighborhoods encircling them. The Birwood Wall, constructed in 1941 to satisfy the Federal Housing Authoritys requirement that the proposed new subdivision of middle-class homes not directly abut the principally black and substandard homes east of the Wall, seemed the perfect solution to both federal authorities and local real estate developers. Never considered in the equation was the effect the Wall would have on the black community, which for years had tried and failed to obtain financing of its own for standard housing construction. Residents continued to adapt, without violence, to the world around them, assisting one another in constructing makeshift abodes as well as supporting black-owned businesses, volunteering their time at the local, segregated schools and worshiping in the many exclusively black churches that had sprung up in the community.

Stepping outside the community was always a challenge, and the various barriers erected to exclude African Americans from equal access to essential city services, not to mention participation in Detroits rich cultural life, only made them appreciate the support and sense of community they enjoyed upon returning home. The two riots that would occur in other parts of the city in successive years would serve to underscore the resilience of the West Eight Mile community. They were determined to work within the system to effect changes that would preserve and protect the community they loved. For nearly one hundred years, they have scaled every barrier designed to frustrate their progress.