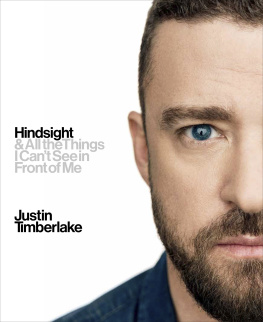

Justin Webb

THE GIFT OF A RADIO

My Childhood and other Train Wrecks

Contents

About the Author

JUSTIN WEBB is the longest-serving presenter of BBC Radio 4s flagship news and current affairs programme Today. For the best part of four decades, he has been a voice on the airwaves or a presence on our TV screens. He joined the BBC in 1984 as a trainee, and has reported from around the world, as a war correspondent in the Gulf and in Bosnia, on the break-up of the former Soviet Union and on the first democratic elections in South Africa. He was Europe Correspondent when the Euro was introduced, and for eight years he was the chief correspondent in Washington DC. Among his awards is Political Journalist of the Year, which he won for his coverage of the Obama presidential campaign. Hes a regular columnist in The Times and for the Unherd website. He lives with his family in South London.

To Mum and Charles

If others examined themselves attentively, as I do, they would find themselves, as I do, full of inanity and nonsense. Get rid of it I cannot without getting rid of myself. We are all steeped in it, one as much as another, but those who are aware of it are a little better off though I dont know.

Michel de Montaigne

1

All at Sea

A week after her wedding day, Mum made an appointment with our GP, rumpled, ginger-haired, stethoscope-wearing Dr Neil, because Charles, her new life partner, my new stepfather, had poured all the milk down the sink. Charles told her that he thought it had been tampered with and Mum felt this might be something that a doctor needed to hear about. Dr Neil was on it: his response perfectly caught the tone of the times.

Mrs Webb: I regret to inform you that your husband is stark staring mad.

And so it all began. For her, for him, for me. No one is to blame for what followed. Far from it. Coping is an underpraised virtue. And coping in the 1970s deserves special recognition. I look back not in anger but in amazement. Each decade has its challenges and there have been far tougher, odder childhoods than mine. But for confusion, for angst, for the clash of tidal forces ready to knock you off your feet, no postwar decade comes close. We were all at sea in the seventies. Often out of our depth, bobbing around, going under.

So its fitting, I suppose, that my own memories start at the waters edge. Its a few years after Dr Neils diagnosis. Im six, maybe seven years old. My stepfather has announced that he is to bathe before we go home from our day trip to the beach. Bathe. Not swim. We live in a world of distressed gentlefolk pretension. He gets up from his towel and pushes back his hair. He is a handsome man of medium build; he has longish hair that needs to be pushed back frequently or oiled and parted vigorously with a plastic comb before he goes to work. Today it sticks up and gives him a Viking swagger.

He strides to the shoreline and stops, as strong swimmers sometimes do, to contemplate the waves. Then he walks, then he dives. Now hes resurfaced and his arms begin their lazy loops through the water. A bit of crawl. On to the back. A couple of powerful butterfly strokes. Hes out to sea. Deep into Lulworth Cove. He seems further out than the rock. Within minutes hes a pinprick. If I hold my finger at arms length from my eye he disappears. Mums next to me. My spade is at rest and the sandcastle abandoned. (Something was always missing that would have made sandcastle-building fun. I did it out of duty. Mum inspected them perfunctorily, not knowing what she was looking for.) We are both squinting into the sun, looking at my stepfather swimming further and further out. The water is flat-calm but deep where he is now. There will be currents, rip tides. Out and out he goes.

And then he comes back.

Many decades have passed but I remember the feeling I had at that moment with vividness undimmed. I was disappointed. Theres no other word. It wasnt hatred or anger or petulance. I was too young to think about the consequences, good or bad, of the actual body being dragged out of the waves and worked on and declared dead. But I formed in that instant the considered opinion that it would have been better if he had drowned. Better for me. Better for her. Better for us. We were together, Mum and I, but we had been joined by him. He was never Dad except in formal letters home from school. At home he was Charles. Mummy, I had asked her once, when I was small: Where did we get Charles? I suggested she went to the pub and got another, superior man. The idea made her laugh. She repeated it often. Inside, though, I think it made her cry. And she was never able to answer my question. It hung there like so much else hung over us through my childhood.

Of course, I didnt actually think of killing him myself that day and he did not actually die. But the disappointment felt like a wet little crime of its own. A slithery thing that only I could feel, like seaweed in the bathing trunks. Could others see it? Could they sense me moving oddly, shifting uncomfortably? Perhaps. It was an ongoing crime: I had the feeling for years to come. People can commit adultery in their minds, and murder, too. You dont have to act on it to feel the guilt.

On the journey home to Bath, in the Hillman Minx with no radio, the three of us were silent. We always travelled in silence but this was deeper. I sat in the back, digging out sand from under my fingernails. The normal tension of the car journey had another layer: I knew what I had thought. And I didnt mind that I had thought it.

That tension in the car was always overlaid with fear. Charles couldnt stand driving behind anyone and overtook constantly, dangerously. What is this man doing? he asked through clenched teeth as we lurched, gears crunching, into the centre of the road for an engine-gunning, flat-out, whites-of-their-eyes race into the path of an oncoming lorry, before pulling back into our lane, just in time. I knew what Id thought. Acknowledging it brought an odd kind of peace.

Charles didnt deserve to die. I dont think he contemplated murdering me or my mother or anyone else. The impact of mental distress is often oblique, not direct. It saps and undermines. It didnt hit me or chase me (and he never did, either) but it lived with me, in my head as much as in his. Charles was a damaged man living with a damaged woman and a damaged child in an era when all mental illness was regarded with a mixture of fear and hilarity. As a reaction to this and with still more ghastly results it was being reinvented as mundane, even, ironically, normal. Maybe it didnt even exist, chirruped those who claimed to be liberated. This was, after all, the era of anti-psychiatry, in which madness was going to be magically reduced to nothing much to worry about. So-called psychiatric survivor movements sought to vindicate those who might think of themselves as justified in their choice of thoughts; any thoughts, whatever they were, could be valid, welcome at the table.

Some of the arguments of the anti-psychiatrists were highly seductive. Schizophrenia in those days a blanket term that had little real meaning did not involve any obvious physical changes to the brain. So was it real? Was it in the minds of those diagnosing it as much as the alleged sufferers from the condition? When the Scottish psychoanalyst R. D. Laing told us that schizophrenia was a sane reaction to an insane world, many people were hearing something they wanted to believe. It seemed to be a liberation to go alongside the burning of bras or the refusal to serve in Vietnam.

Next page