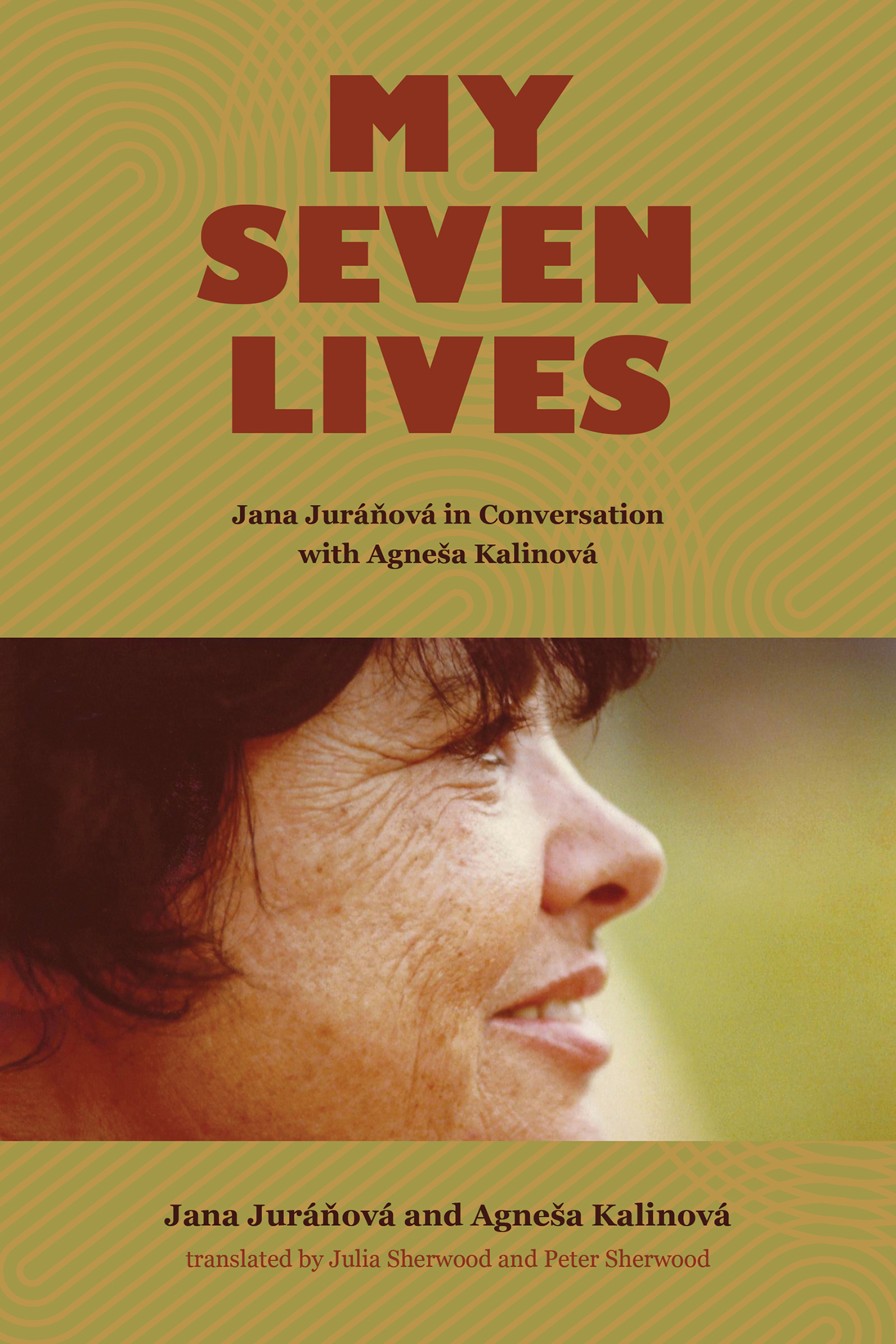

MY SEVEN LIVES

MY SEVEN LIVES

Jana Jurov in Conversation with Agnea Kalinov

Jana Jurov and Agnea Kalinov

translated by Julia Sherwood and Peter Sherwood

Purdue University Press | West Lafayette, Indiana

Copyright 2021 by Jana Jurov and Julia Sherwood. All rights reserved.

Translation copyright 2021 by Julia and Peter Sherwood.

Printed in the United States of America.

Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available at the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-1-61249-719-8 (hardback)

ISBN 978-1-61249-720-4 (paperback)

ISBN 978-1-61249-721-1 (epub)

ISBN 978-1-61249-722-8 (epdf)

Cover image: Courtesy of the estate of Karol Skipsk

This book was published with financial support from SLOLIA, Centre for Information on Literature, Bratislava.

This project has been supported using public funds provided by Slovak Arts Council. This publication reflects the views only of the author, and the Council cannot be held responsible for the information contained therein. | |

To the generation that, after the horrors of World War II and the Holocaust, placed their hopes in the more humane world promised by socialism, and found themselves suffering for their beliefs, yet never gave up the fight for justice and human rights.

Contents

Preface

My Twentieth Century With Agnea Kalinov

I first met Agnea Kalinov more or less by chance at the Karlovy Vary festival, in the early 1990s. The friend who introduced us had sung her praises: You really must meet her, she has this beautiful, sunny face. Although Agnea knew nothing about me, she was warm and very kind to me. And so, when I found myself in Munich in 1992 taking up a new position at the Czechoslovak service of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, I already had a friend there. Nearly two decades have passed since, and we have kept in touch.

Sometime in 2010 the writer and theater maker Anka Gruskov mentioned casually over a cup of coffee that it would be a great idea for someone to conduct a book-length interview with Agnea. Neither of us had the capacity to take it on at the time and the idea fell off my radar, but I revived it some time later as I became increasingly aware that there were major gaps and flaws in my own knowledge of the history of my part of the world. The older I am, the more I feel the need to fill these gaps. Thus the idea of conducting this interview coincided with my need to revise my knowledge of the past century, supposedly so short but all the more harrowing.

Agnea was born at the time of the first Czechoslovak Republic, to parents still bearing traces of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy in their hearts. She grew up between two world wars, in a period that included both the emergence of cultural and political avant-gardes as well as of fascism. World War II and the Holocaust left their cruel mark on her familys fate. In the late 1940s she was among those for whom the new era opened new opportunities. But soon, by the early 1950s, the totalitarian regime showed its true colors, afflicting many around her. As a staff writer for Kultrny ivot (Cultural Life), one of the key opinion-forming periodicals of the period, Agnea was involved in the endeavor to liberalize the Czechoslovak variety of totalitarianism. The all-too-brief period of the Prague Spring was followed by a harsh period of normalization, which brought persecution upon many of her friends and her loved ones as well as herself, culminating in her imprisonment. By the late 1970s life in Czechoslovakia had become untenable, compelling her and her family to emigrate to Munich, where she went on to work for Radio Free Europe and continued to live after her retirement, visiting Slovakia often and with much pleasure.

While planning the interview I came to realize that it would be a real shame not to make use of her phenomenal memory, openness, and gift for storytelling. My friends and colleagues at the publishing house ASPEKT loved the idea as well. We just had to hope that Agnea would agree to our proposal. After thinking about it for a while, she sent me all sorts of material, press clippings, and articles. Preparing for a conversation covering several historical periods was a daunting, but also fascinating, task. I reread a thesis on Agnea by a student of journalism, all four volumes of the autobiography of her husband, Ladislav Jn Kalina, published in the 1990s by Marenin PT, and the memoirs of many others who had lived through those years, as well listening to the recording of a video interview with Agnea conducted by the Milan imeka Foundation as part of their oral history project on Holocaust survivors. Having done my homework, I set out for Munich.

In the summer of 2011, I twice spent several days at Agneas Munich home, recording forty-four hours of conversation. While transcribing the tapes, I searched for the best way of capturing my interviewees unique personality, and I found feminist research on the theory and practice of oral history extremely helpful. Our lives play out in the public as well as the private space, which are inseparable, and the more complex their intermingling, the more seamless is the picture that emerges. This also proved to be the case with My Seven Lives.

The final shape of this book is the result of some nine months of focused and intensive work by myself and Agnea, and my colleagues at ASPEKT.

The resulting lesson in twentieth-century history ended up being a gripping and stirring experience for me and will also be, I hope, for those who pick up this book.

Jana Jurov, 2012

1

Childhood and Adolescence

19241942

You were born ten years after the outbreak of the Great War.

Believe it or not, Ive never thought of it in that way! To me the Great War was something ancient, even if not antediluvian. I saw no direct link between it and my own life, even though all the grown-ups around me had lived through the war and kept telling stories about it. Austria-Hungary, the old monarchy, seemed like some distant memory, a totally different world. It wasnt until much later that I realized what a deep mark it had left on the people around me and my own childhood. In fact, theres something thats been a lifelong motif for me, something Central European: discontinuity. Theres a sudden upheaval, brought on by outside circumstances, unwarranted interference by external forces, which wipes out everything, or at least much of what we have taken for granted, and you have to start again from scratch. And each time its like the beginning of a new era.

You grew up in Preov but you were actually born in Koice, is that right?

From my first days at high school, or gymnzium as it was called, I felt a bit awkward about the fact that I was born in Koice. Or rather, that Koice had been recorded as my birthplace only because my mother went there to give birth because at the time there wasnt yet a maternity clinic in Preov. So out of embarrassment I resorted to a half-truth and pointed out that my parents began their married life in Koice, as it was my fathers hometown. But the truth is that they moved to Preov at least two years before I was born, when he was appointed director of the Preov branch of the Slovensk veobecn verov banka (the Slovak General Credit Bank). In every other respect, I identified completely with Preov and was a local patriot, just like many of our friends.