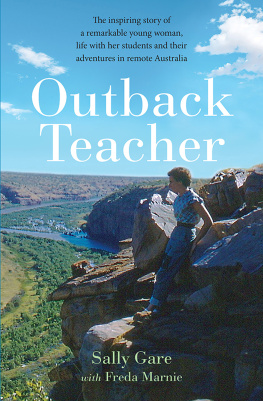

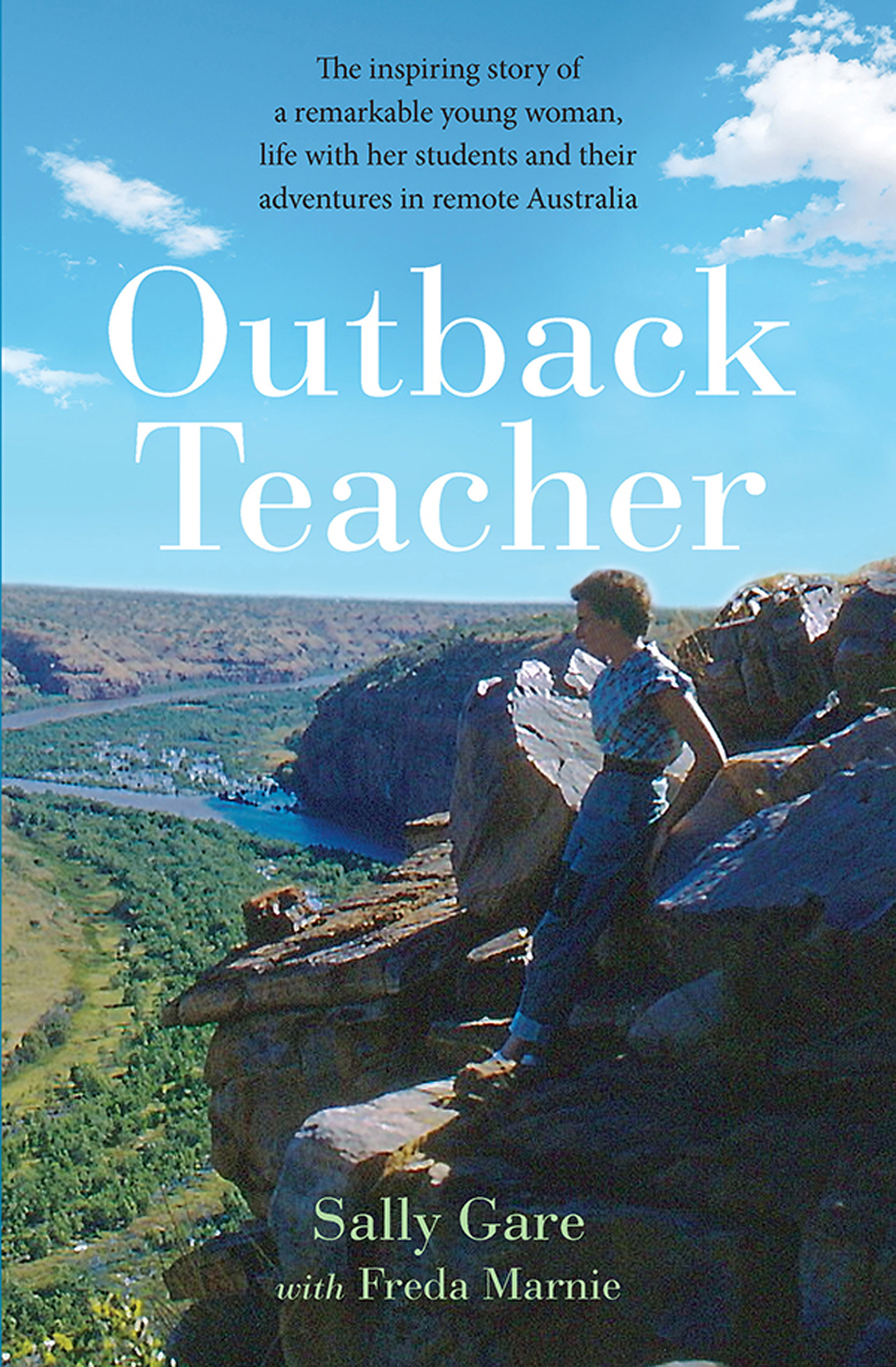

All photographs are from Sally Gares personal collection.

First published in 2022

Copyright Sally Gare and Freda Marnie 2022

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone:(61 2) 8425 0100

Email:

Web:www.allenandunwin.com

ISBN 978 1 76106 534 7

eISBN 978 1 76106 425 8

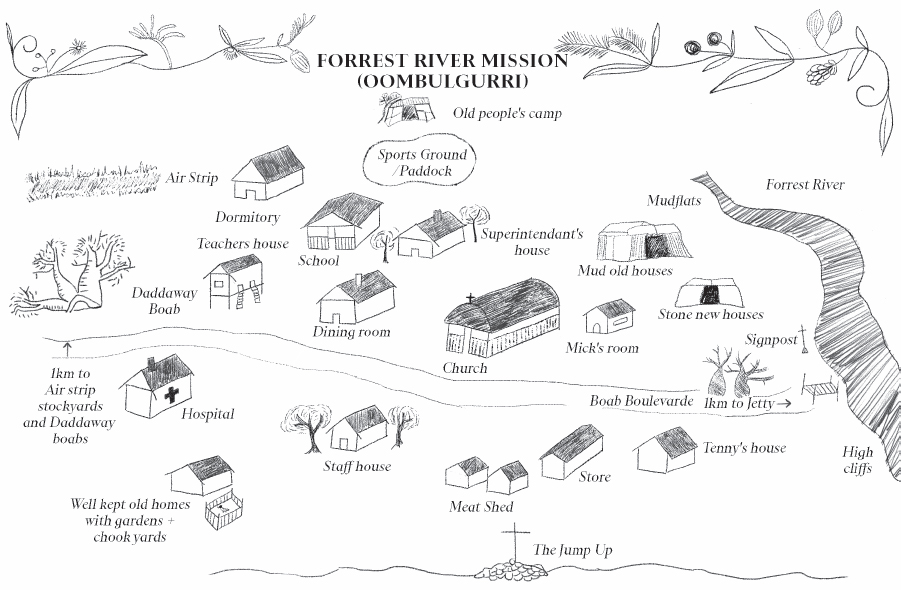

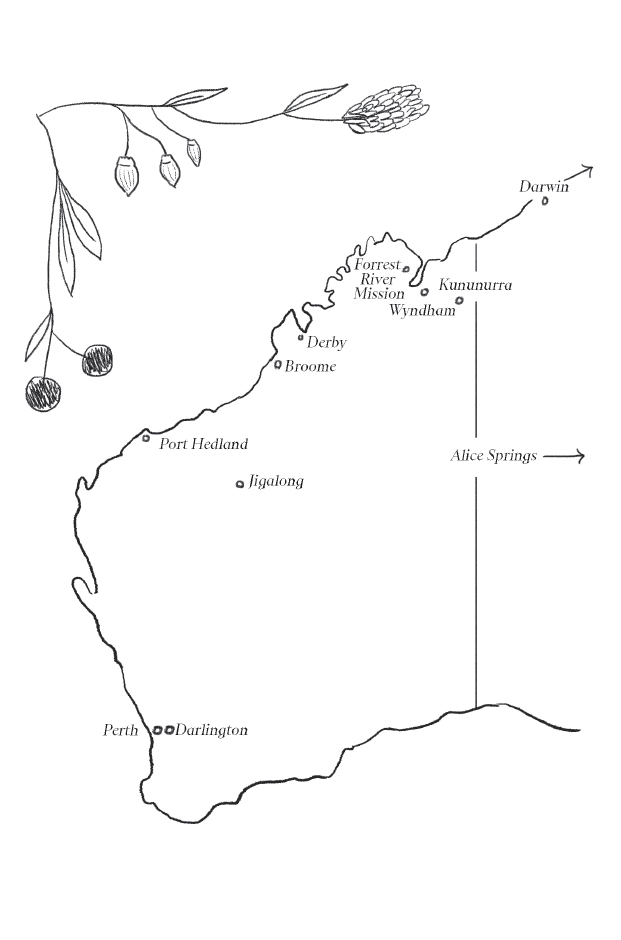

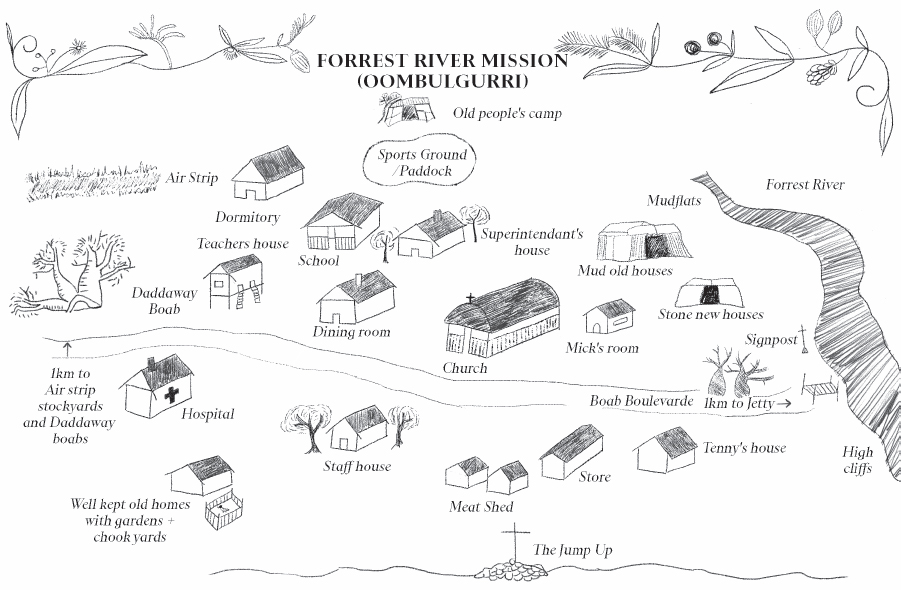

Maps by Mika Tabata

Set by Midland Typesetters, Australia

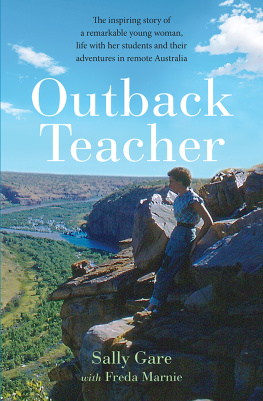

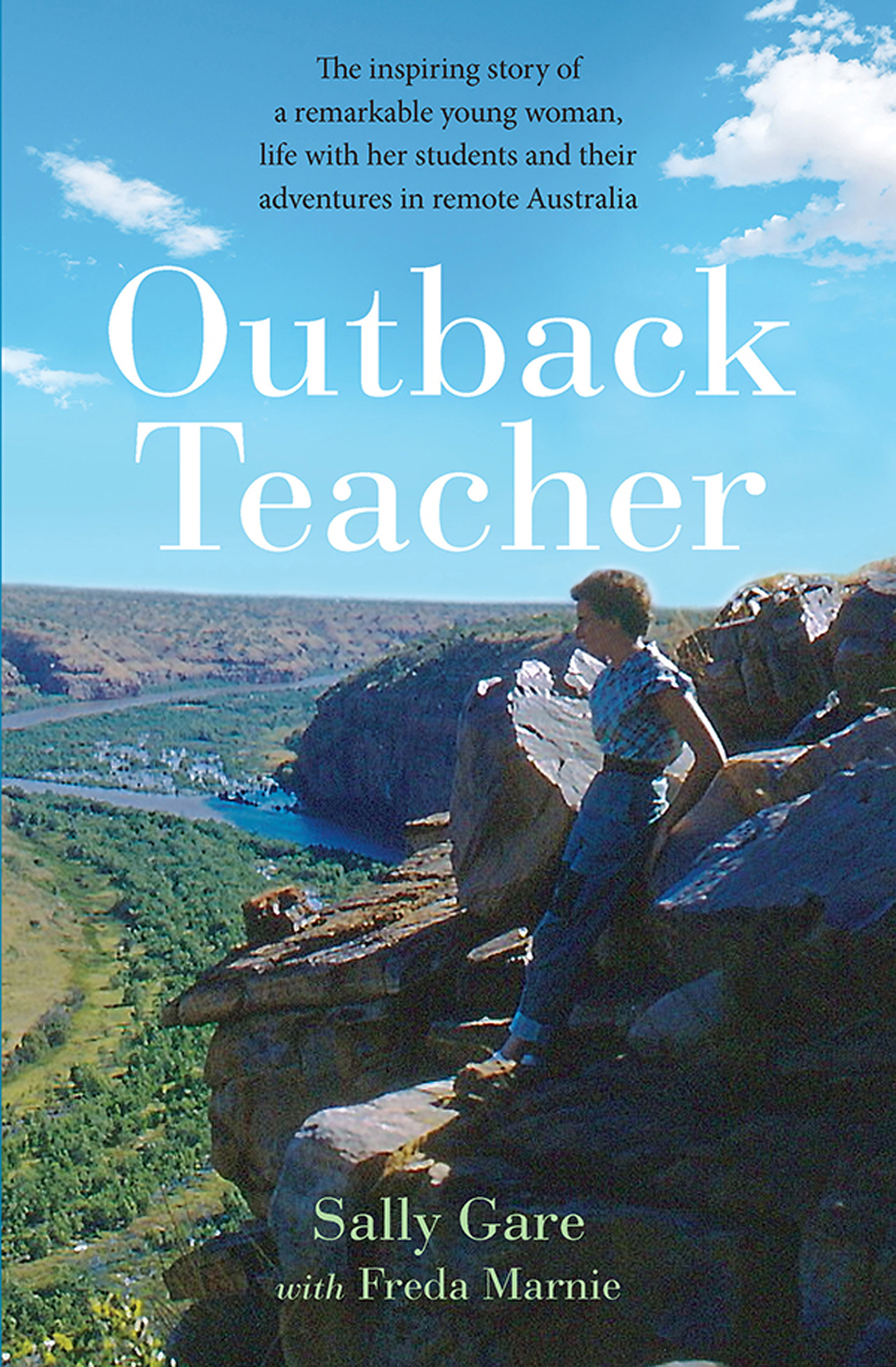

Cover design: Mika Tabata

Cover photographs: Sally Gare

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are advised that this work contains the names and images of individuals who may have passed away and that some historical language has been used.

We acknowledge the traditional owners of Country throughout Australia and their connections to land, sea and community. We pay our respects to their Elders past and present and extend that respect to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

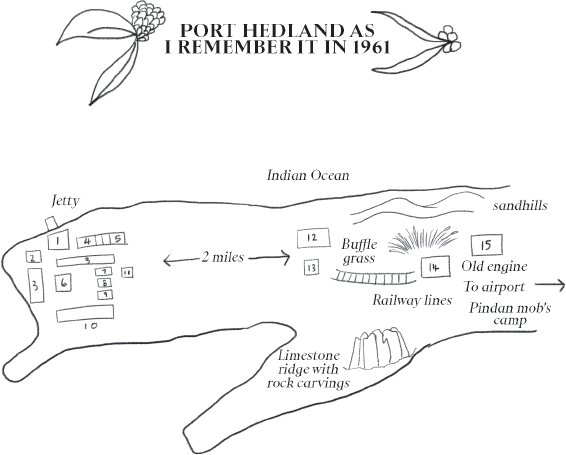

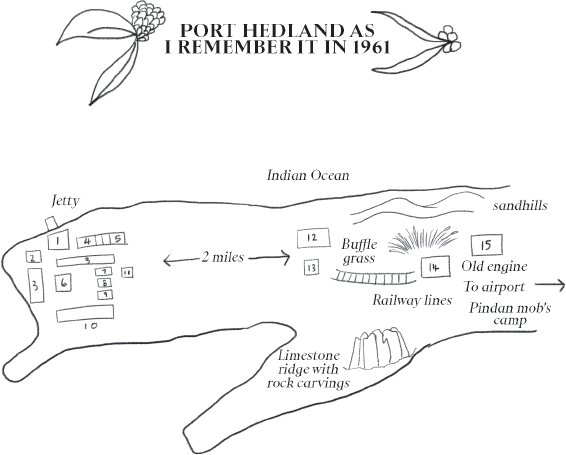

1Tennis and Basketball Courts

2Pier Hotel

3Shops & Offices

4Esplanade Hotel

5Elders Shop

6Open Air Picture Gardens

7Catholic School

8Glasses Home

9Anglican Church

10Offices & Homes

11United Church

12New School on the Hill

13Nuns House

14Loco School

15Native Hospital

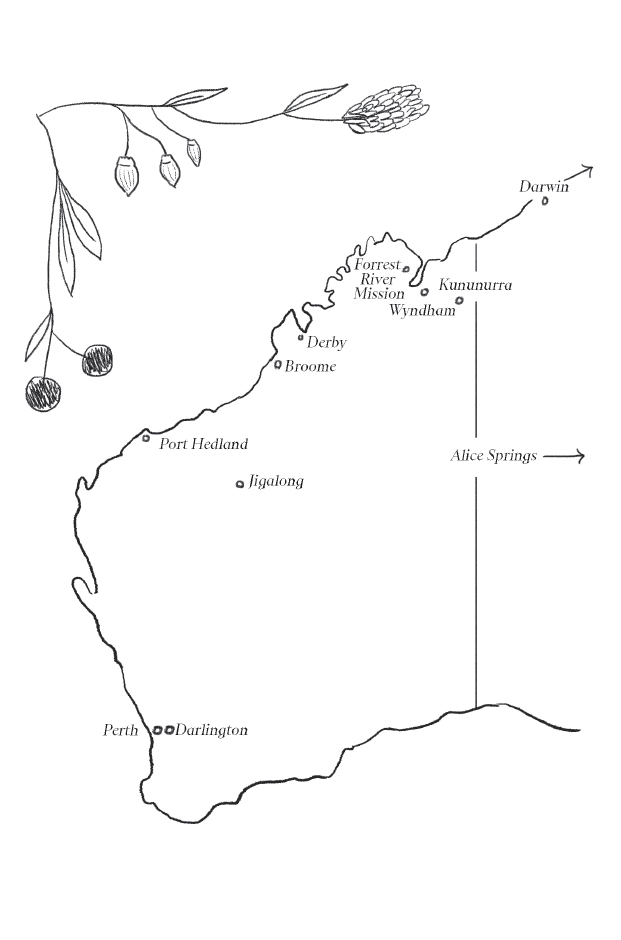

With the threat of a cyclone imminent, we were having a cloudy, wet and bumpy trip in the Douglas DC-3. It was February 1956 and I was just out of teachers college, heading to my first posting, an Aboriginal mission run by the Church of England. Forrest River Mission, or FRM as it was sometimes known, was outside Wyndham, near the Western Australian and Northern Territory border.

The trip by plane to Wyndham from Perth was a 3200-kilometre journey up the west coast of the vast state of Western Australia. With stops at Geraldton, Carnarvon, Port Hedland, Broome, Derby and finally Wyndham, the flight could take up to thirteen hours, depending on loading and unloading of people and supplies at each airport. The DC-3 we were flying up in was an unpressurised twin-propeller plane that could carry up to twenty-eight passengers, and we were bounced around through the hot, rough air of the tropical north for literally hours on end. Two of my travelling companions on that first trip north were the missions new matron, Mrs OReilly, and her young son Mick. We hadnt talked much on the way up as the poor matron was unwell from the turbulent weather.

People used to say if you lived in Wyndham you didnt go to hell when you died; youd already been there. It was hot and, in February, extremely humid, a far cry from Perths dry heat. After we arrived, the unsteady matron, her son and I caught the airline bus from the airport to town. I was quite concerned about her; she didnt look well.

In my first glimpse of the norwest town, as we headed down the main street leading to the port, I was amazed at the strange bulbous bottle-shaped trunks of the large boab trees that were dotted along the street. Nearly all the buildings in the main streeta two-storey pub, one cafe and a few shopswere made out of corrugated iron.

I later learnt that the twenty-bed hospital had only one permanent doctor, and that any serious cases had to be flown to Derby with the Royal Flying Doctor Service (RFDS). The meat works was the biggest employer, but it only operated between July and September, the coolest time to be there.

The population of Wyndham at this time numbered about four hundred white people living in town and two hundred Aboriginal people living out in two camps, Three Mile and Six Mile, named for their distance from the centre of town. We called people black and white back then and, even with the work I do today, my Aboriginal friends dont mind me saying black or white to describe ourselves.

The missions handyman, Bob Morrow, met us in town. He too was concerned about the matrons health and tried to get us accommodation in town at the pub for the night so she could rest up. When he found there wasnt a spare room, he decided wed go out on the late afternoon tide. I had no idea what that would entail but was about to find out.

There was a huge difference in the water levels between high and low tide at Wyndham. That day in early February, the incoming tide would be at 9 p.m. and 3 a.m., and we aimed to be at the mouth of the Forrest River for the 9 p.m. change to make it all the way up the river to the mission. When the tide was on its way out in Wyndham, as it was on this occasion, we were forced to walk out for about fifty metres over wet rocks and broken glass.

With Bob leading the way, we waded out to the little open four-metre launch, holding our luggage over our heads. When we finally clambered in over its side, we found it was already full, occupied by the local Oombulgurri people and mission supplies. So, we squeezed in where we could just as night fell. It was only when we were on the boat that I learnt we had been lucky not to see any saltwater crocodiles!

The dirt road to Oombulgurri from Wyndham was yet to be fully constructed. It would ultimately be about 210 kilometres long, but it was pretty much a rough, uncharted track back then, prone to washouts from the summer Wet Season. To get safely to the mission, you basically needed to go by either boat or plane.

It felt like quite an adventure as we putted out into the West Arm of the Cambridge Gulf and then waited at the mouth of the Forrest River for the tide to change from outgoing to incoming, to take us all the way to the upper reaches of the river, and on to the mission. Despite having left Perth at five that morning, and with night upon us, we still had a long way to go. Bob told us that it could take anything from eight hours to thirteen hours to travel the sixty miles (one hundred kilometres) from Wyndham to the mission along the windy Forrest River, more if you became stuck in the mud. In the time ahead, I was to find that this happened quite often.

Bob expertly brewed us a cup of tea to while away the time as we waited for the tide to change. When young Mick OReilly complained to his mother that he was hungry, I heard her tell him, Youre in the bush now. What you cant do today, theres always tomorrowthat includes eating. I nodded silently to myself in agreement. I was expecting a very basic, isolated time ahead, but I was determined to do it.

Next page