for Dick, as always

CONTENTS

Praise for

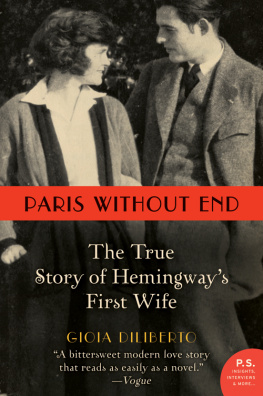

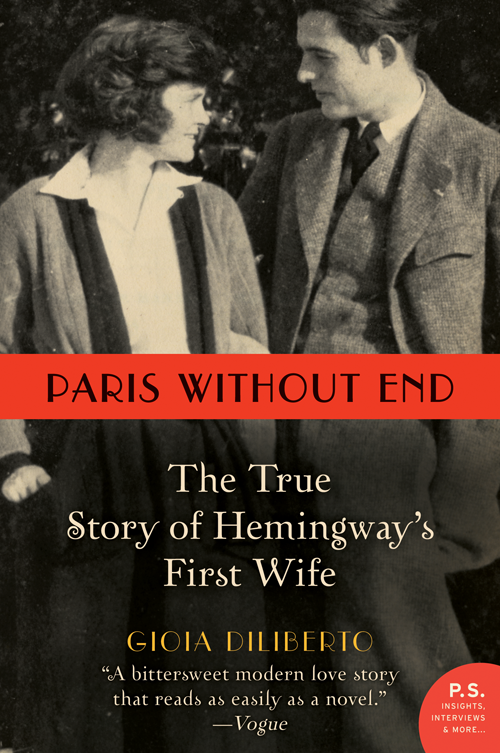

Paris Without End

PREFACE

TO THE 2011 EDITION

One warm July evening in 1992, I gave a talk to agroup of Hemingway fans whod gathered to celebrate the authors birthday at theHemingway Museum in Oak Park, Illinois. As I stood at the podium looking out atthe crowd of mostly men, some of whom resembled stage-three Hemingways withwhite beards and big bellies straining against the buttons of safari jackets, Ifelt a bit out of place. I wasnt a Hemingway scholar or biographer. My onlyclaim to Hemingway expertise was that I had written a book about HadleyRichardson, the writers first and most beloved wife. Judging by the peevishglare of the Papa lookalike in the front row, however, that didnt countfor much here.

Wives had it hard in those days. In most Hemingwaybiographiesa shelf-full appeared in the mid-1980s, following the openingof Hemingways papers at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum inBostonHadley, and Hemingways three subsequent wives, are shadowy figures,characters not fully realized in their own right. Hadley, in particular, isoften portrayed as a supplicant, even a doormat, a picture that fits nicely withthe popular myth of Hemingway as a he-man writer, adventurer, carouser, andlover.

Yet all that goes against what I discovered whilewriting this book. Hadley was far more complex than the biographies would haveus believe. Much the same could be said for the other Hemingway wives, too.

When I began work on Hadley in the late 1980s, a flurry of books about iconic womensuchas Amelia Earhart, Marie Curie, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Harriet BeecherStowehad been recently published, sparked by the womens movement of thesixties and seventies. Still, the perceived role of women in America was in suchflux that to write about a woman whose only career was marriage seemed, at thetime, well, antifeminist.

Today, a generation later, almost the opposite istrue, and as the place of women in the world of achievement is widelyrecognized, wives are being considered anew. Fresh insights into creative geniusare revealed when explored through the eyes of those whove nurtured it, andweve seen a spate of books that illuminate the crucial role of women in theirhusbands careers. On television, too, wives are enjoying a golden moment: The Good Wife, Big Love, Desperate Housewives, ArmyWives, and the Real Housewives series might be frivolousentertainment, but on a deeper level these shows appeal to the same yearning fordomestic tenderness that pervades much of Hemingways work.

For all his macho posturing, Hemingway at his bestwrote love stories that brilliantly charted the emotional nuances inrelationships between men and women. His great talent was in evoking the mostintimate moments of longing, and all his fictional love stories flow from thecentral love story in his own lifehis marriage to Hadley. She is chieflyremembered, of course, for her portrayal in Hemingways poignant memoir of hisyouth in Paris, A Moveable Feast, where his remorsefor leaving her can be felt on every page.

That is, on every page of the books original 1964edition. In 2009, a restored edition was published, and it included materialthat had been rejected by A Moveable Feast s firsteditor, Mary Hemingway, the writers fourth and final wife. The tale of the twoeditions, it turns out, is the story of a battle among Hemingways heirs overhow his marriage to Hadley should be remembered.

A Moveable Feast wasthe last thing Hemingway worked on, and it was unfinished at his death. MaryHemingway prepared the manuscript for publication, leaving out materialsympathetic to Pauline, Hemingways second wife. Paulines son Patrickspeculated in the New York Times that Mary wanted tocourt favor with Hadley, who owned the rights to TheFarm, a valuable painting by Mir, that had been in Marys possessionfor years.

In Marys version, Pauline, a wealthy Vogue editor, is portrayed as a conniving homewrecker, the snake who destroyed the Hemingways Garden of Eden. The restoredversion contains material cut by Mary that mentions the unbelievable happinessHemingway enjoyed for a time with Pauline and his acceptance of blame in thebreakup of his first marriage. In reconstructing the Hemingways lives, I drewheavily on these then-unpublished outtakes.

There Is Never Any End to Paris, the wrenchinglast chapter in Marys version, concludes with the abandonment of Hadley, whichwas not the ending Hemingway intended, according to Paulines grandson Sean,who, in editing the restored edition, moved this chapter to an appendix.Hemingway did not want an ending that left Hadley forlorn and alone, Sean said.The new edition closes with Hemingway reminiscing about war and writing with hisfriend, poet and sportswriter Evan Shipman .

Ultimately, I prefer the first version, which isnot only a smoother, more coherent read but also more powerfully expresses theregret Hemingway felt for betraying Hadley. It is this mournful regret, afterall, that gives the memoir its heart-stopping force. In the books last lines,Hemingway evokes the eternal Paris of his imagination, where his love for Hadleyand their life together lives on: There is never anyending to Paris and the memory of each person who has lived in it differsfrom that of any other. We always returned to it no matter who we were orhow it changed or with what difficulties, or ease, it could be reached.Paris was always worth it and you received return for whatever you broughtto it. But this was how Paris was in the early days when we were very poorand very happy.

I first read A MoveableFeast on my honeymoon in Paris in 1980, and I remember my chesttightening at the sentence I wish I had died before I loved anyone but her.Like Hadley, I was a young wife besotted with a man and a city, and I foundHemingways description of the death of love disturbing. How could he leavesomeone so seemingly perfect as Hadley? Why didnt he see through Paulinesscheming? And why didnt Hadley fight harder for her marriage?

These questions obsessed me, though it wasnt untilyears later that I finally set out to tell Hadleys story. One of the firstthings I did was contact Alice Sokoloff, a musician and writer who played pianoduets with Hadley in the 1970s, when the two women were neighbors in Chocorua,New Hampshire. Alice, a vibrant, cultured grandmother then in her seventies,invited me to visit her in Katonah, New York, and we spent several hours talkingover cups of tea in her small apartment. When I got up to leave, she amazedme by handing over a box of tapes with a wry smile, saying, I think youllfind these very interesting.

I slept little the next few days as I transcribedthe tapes, all conversations between Alice and Hadley in the early seventies.They were scratchy with age and in some places difficult to understand; still, Icouldnt stop listening. Here was the real Hadleywittier and more astringentthan the Hadley of A Moveable Feast, but also justas warm, melancholy, and intelligent. Hadley spoke frankly about her life withHemingway, and Alice felt much of it was too intimate to include in her ownshort book, The First Mrs. Hemingway, published in1973 when Hadley was still alive. (She died in 1979.) The tapes gave me not onlya wealth of rich, new material to draw on, but also the rare opportunity tolisten to a subject talk about her life from beyond the grave. I heard Hadleysvoice, her laugh, her sighs, her manner of expression, and all the clues tocharacter these things provide.

I was immensely lucky, too, in having access tomore than one thousand pages of Hadleys letters to Hemingway, which he hadsaved throughout his life. With these letters, Alices tapes, and the scores ofinterviews I conducted, I was able to bring Hadleys interior world tolife, to probe her emotions and re-create her personality and character.