Table of Contents

Guide

Also by Lorna Gibb

LADY HESTER

Copyright 2014 by Lorna Gibb

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

The picture credits on page 321 constitute an extension of this copyright page. Every effort has been made to contact the copyright holders of the material reproduced in this book. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publisher will be pleased to make restitution as the earliest opportunity.

First published in Great Britain in 2013 by Macmillan

Typeset by SetSystems Ltd, Saffron Walden, Essex

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

ISBN 978-1-61902-374-1

COUNTERPOINT

1919 Fifth Street

Berkeley, CA 94710

www.counterpointpress.com

Distributed by Publishers Group West

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

In memory of my beloved dad,

IAN GIBB

19372011

And for our dearest friend,

PAUL COOMBS

19532007

Contents

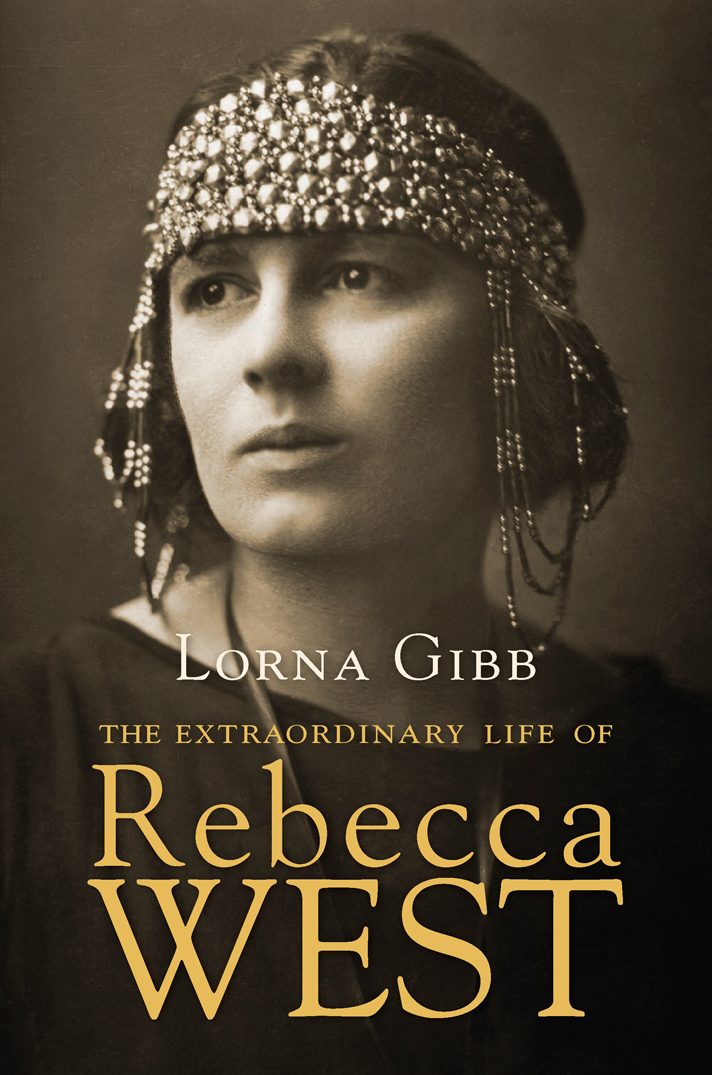

A woman of surprising contradictions, socialist and Thatcherite, a defender of womens suffrage, a disciple of St Augustine and lover of H.G. Wells, successful novelist and astute, prophetic chronicler of the Near East: Dame Rebecca West was all of these, and more, much more. She engaged passionately with the events of almost a century. A uniquely talented personality, West was showered with rewards and tributes for her novels and journalism during her lifetime. Sadly her eclecticism was her undoing; her writing could not be categorized into those pigeon holes so beloved of the literati and her literary status was never as secure as that of contemporaries like Virginia Woolf.

Her success also brought domestic disharmony. Her son, the writer Anthony West, thought her a terrible mother, and the kind of familial disagreements normally played out within the family became a very public and acrimonious row, observed by hundreds, a kind of reality TV acted out by correspondence, the effects continuing even after Rebeccas death.

Wests troubles were universal and timeless. The conflicting demands of motherhood and career, the longing for love and companionship tempered by the need for independence, were spelled out in letters and diaries, articles and books, while the world changed, bringing new dilemmas and consequences. Her struggles are as pertinent now as they have always been. Wests private life was entwined with political events, the unfolding history of a century symbiotically related to the mundane and the personal, the minutiae of her life. Her diary entries and notebooks present something more than pictures from a lost age; they form a map showing the places we have come from.

When travelling in a region I always ask friends who have been there before me for advice on a book to take that will aptly capture or add to my experience. During such a trip in Eastern Europe Black Lamb and Grey Falcon was my introduction to Rebecca West. The friend who recommended it was a diplomat. He had been told to read this very large tome for a prior posting and had begun to do so somewhat reluctantly. It was the 1980s. Following Titos death, Yugoslavia was faced with an economic crisis; Serbian nationalism, with Kosovo as its symbol, was growing rapidly. Some way into Wests book, my friend, caught up in the local unrest, was hooked, finding answers to, and questions about, the things he was witnessing some fifty years after she had written it.

My own experience was the same, except my friend, like so many men enchanted by Rebeccas words, fell a little in love with the author too. This is part of Wests skill, an ability to act as a social commentator on a period that was yet to come, and, while doing so, to beguile and enchant her reader.

Looking at my book collection, it seems that, of those books by West that I have acquired over the years, a disproportionate number were gifts. Three of her novels as well as The Meaning of Treason, Henry James and St Augustine were all delightful presents. For me, as for so many of my peers, West is a shared pleasure, passed on, read, then later discussed in dingy student Soho coffee shops in the eighties, or more recently, over wine at a picnic in a garden. Perhaps the most wonderful thing of all is that, because of the eclectic nature of Wests writing, these exchanges could be on so many topics: literature, espionage, travel, the role of women, all originating from a book or article by a single author. West dealt with big topics, many of which still reverberate today, such as the integration of Eastern and Western religious faiths, the contradictions of femininity and power, the causes and effects of wars. Yet, in her considerations, she did not lose sight of the domestic concerns, those personal and intimate stories taking place against the backdrop of social change and unrest. As she once stated in an article for The New Yorker, she did not wish to write history as Gibbon liked to record it, but a history of the endless troubles of everyday life.

In a letter to V.S. Pritchett, written in July 1941, West lamented our curious national habit of writing monographs in one subject without looking into its context. In Wests own biographies she was careful not to make this mistake. Bernard Levin, in a 1981 Radio broadcast for the BBC, praised the astonishing world view of her writing. The extraordinarily rapid developments of the twentieth century were a mirror to Wests remarkable life. They were also the cause of many of that lifes difficulties.

Rebecca West was a pseudonym, a moniker chosen hastily from an Ibsen play, because Rebecca didnt want her mother to see the family name displayed on a poster about an article she had written in support of womens suffrage. West was born Cicely Isabel Fairfield, in 1892; it was, she said, a Mary Pickford of a name for someone blonde and pretty and wouldnt have suited a professional writer through life at all. For Wells and for her son, she was Panther; for one of her lovers, Tommy, she was a firefly; and to her husband, Henry Andrews, she was both Cicely Andrews and Rebecca.

These many names came to represent different aspects of her personality. Rebecca West was a successful, feted writer and a shining success, loved by her friends and admirers. Rebecca once wrote to one of her closest confidantes, Emanie Arling, that she loved her most, of all her friends, because she called her Rebecca and never anything else. But Cicely Andrews was a lonely wife who felt that many of her friends pitied her for Henrys infidelities and laughed at her behind her back.