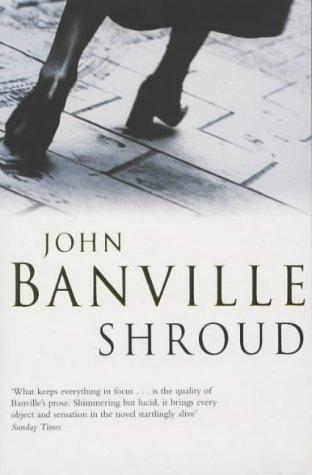

One part Nietzsche, one part Humbert Humbert, and a soupcon of Milton's Lucifer, Axel Vander, the dizzyingly unreliable narrator of John Banville's masterful new novel, is very old, recently widowed, and the bearer of a fearsome reputation as a literary dandy and bully. A product of the Old World, he is also an escapee from its conflagrations, with the wounds to prove it. And everything about him is a lie.

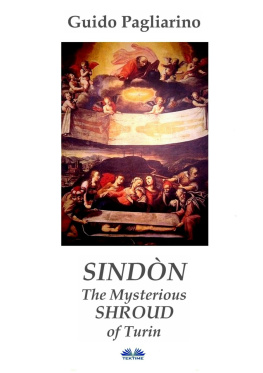

Now those lies have been unraveled by a mysterious young woman whom Vander calls "Miss Nemesis." They are to meet in Turin, a city best known for its enigmatic shroud. Is her purpose to destroy Vander or to save him-or simply to show him what lies beneath the shroud in which he has wrapped his life? A splendidly moving exploration of identity, duplicity, and desire, Shroud is Banville's most rapturous performance to date.

Alex Vander is a fraud, big-time. An elderly professor of literature and a scholarly writer with an international reputation, he has neither the education nor the petit bourgeois family in Antwerp that he has claimed. As the splenetic narrator of this searching novel by Banville (Eclipse), he admits early on that he has lied about everything in his life, including his identity, which he stole from a friend of his youth whose mysterious death will resonate as the narrator reflects on his past. Having fled Belgium during WWII, he established himself in Arcady, Calif., with his long-suffering wife, whose recent death has unleashed new waves of guilt in the curmudgeonly old man. Guilt and fear have long since turned Vander into a monster of rudeness, violent temper, ugly excess, alcoholism and self-destructiveness. His web of falsehoods has become an anguishing burden, and his sense of displacement ("I am myself and also someone else") threatens to unhinge him altogether. Then comes a letter from a young woman, Cass Cleave, who claims to know all the secrets of his past. Determined to destroy her, an infuriated Vander meets Cass in Turin and discovers she is slightly mad. Even so, he begins to hope that Cass, his nemesis, could be the instrument of his redemption. Banville's lyrical prose, taut with intelligence, explores the issues of identity and morality with which the novel reverberates. At the end, Vander understands that some people in his life had noble motives for keeping secrets, and their sacrifices make the enormity of his deception even more shameful. This bravura performance will stand as one of Banville's best works.

A scholar and born liar, the elderly but still contentious Axel Vander is about to have his cover blown when an equally contentious young woman enters his life. Banville's lucky 13th novel.

We set up a word at the point at which our ignorance begins, at which we can see no further, e.g., the word "I," the word "do," the word "suffer": - these are perhaps the horizon of our knowledge, but not"truths."

ONE

Who speaks? It is her voice, in my head. I fear it will not stop until I stop. It talks to me as I haul myself along these cobbled streets, telling me things I do not want to hear. Sometimes I answer, protest aloud, demanding to be left in peace. Yesterday in the baker's shop that I frequent on the Via San Tommaso I must have shouted out something, her name, perhaps, for suddenly everyone in the crowded place was looking at me, as they do here, not in alarm or disapproval but simple curiosity. They all know me by now, the baker and the butcher and the fellow at the vegetable stall, and their customers, too, hennaed housewives, mostly, plump as pigeons, with their perfume and ugly jewellery and great, dark, disappointed eyes. I note their remarkably slender legs; they age from the top down, for these are still the legs, suggestively a little bowed, that they must have had in their twenties or even earlier. Clearly I interest them. Perhaps what appeals to them is the suggestion of the commedia dell'arte in my appearance, the one-eyed glare and comically spavined gait, the stick and hat in place of Harlequin's club and mask. They do not seem to mind if I am mad. But I am not mad, really, only very, very old. I feel I have been alive for aeons. When I look back I see what seems a primordial darkness, scattered with points of cold, hard light, immensely distant, each from each, and from me. Soon, in a few months, we shall enter the final decade of this millennium; I will not live to see the next one, a matter of some regret, the previous two having generated such glories, such delights.

Yes, I have returned to this arcaded city, unwisely, it may be. I rented a place in one of the little alleyways hard by the Duomo, I shall not say which one, for reasons that are not entirely clear to me, although I confess I worry intermittently about the possibility of a visit from the police. It is not much, my bolt-hole, a couple of rooms, low-ceilinged, dank; the windows are so narrow and dirty I have to keep a table lamp burning all day for fear of falling over something in the half dark. I would not wish to be found dead here, the door broken down, my landlady screaming, and I in who knows what mode of disarray. She is, my landlady quella strega! a widow, and of a decidedly histrionic bent. She tells me this used to be the city's red light district, and gives me a look the import of which I do not care to speculate upon, widening her eyes and holding her head far back, affording me an unpleasant view into the caverns of her nostrils. I always suspected I would end up like this, an outcast, stumping the back streets of some anonymous city, talking to myself and being stared at by passers-by. Yet I chose to come back here, though not out of fondness, certainly. Turin resembles nothing so much as a vast, grandiose cemetery, with all this marble, these monuments, these gesturing statues; it is no wonder poor N. went off his head here, thinking himself a king and the father of kings and stopping in the street to embrace a cabman's nag. They lost his luggage, too, as once they did mine, sent it to Sampierdarena when he was headed in the opposite direction; forever after he could not hear that melodious place-name without a snarl of rage.

Enough of these vagaries. I am going to explain myself, to myself, and to you, my dear, for if you can talk to me then surely you can hear me, too. Calmly, quietly, eschewing my accustomed gaudiness of tone and gesture, I shall speak only of what I know, of what I can vouch for. At once the polyp doubt rears its blunt and ugly head: what do I know? for what can I vouch? There exists neither "spirit," nor reason, nor thinking, nor consciousness, nor soul, nor will, nor truth: all are fictions So the crazed philosopher declares, swinging his mighty hammer. Yet the notion haunts me that I am being given one last chance to redeem something of myself. I am not speaking of the soul, I am not that far gone in my dotage. But there may be some small, precious thing that I can buy back, as once I bought back Mama Vander's silver pill-box from the pawnbroker's. It occurs to me to wonder if that might have been your real purpose, not to expose me and make a name for yourself at all, but rather to offer me the possibility of redemption. If so, you have already had an effect: redemption is not a word that up to now has figured prominently in my vocabulary. But then your motives were never clear to me, no more, I suspect, than they were to you. Perhaps you did indeed betray me, and someday soon a publication will pop up from the presses in an obscure corner of academe with a posthumous essay in it, by you, on me, and I shall be disgraced, laughed at, hooted out of the lecture hall. Well, no matter.