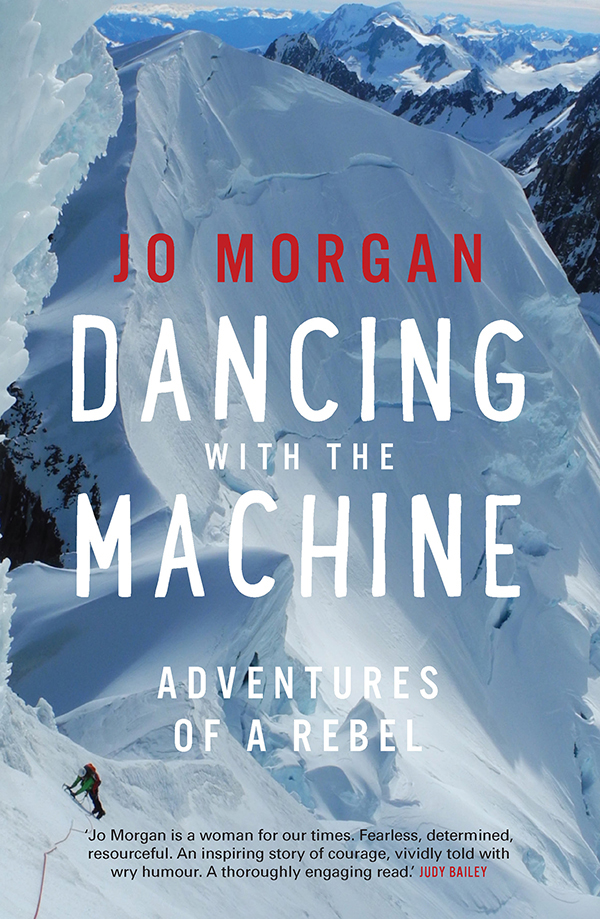

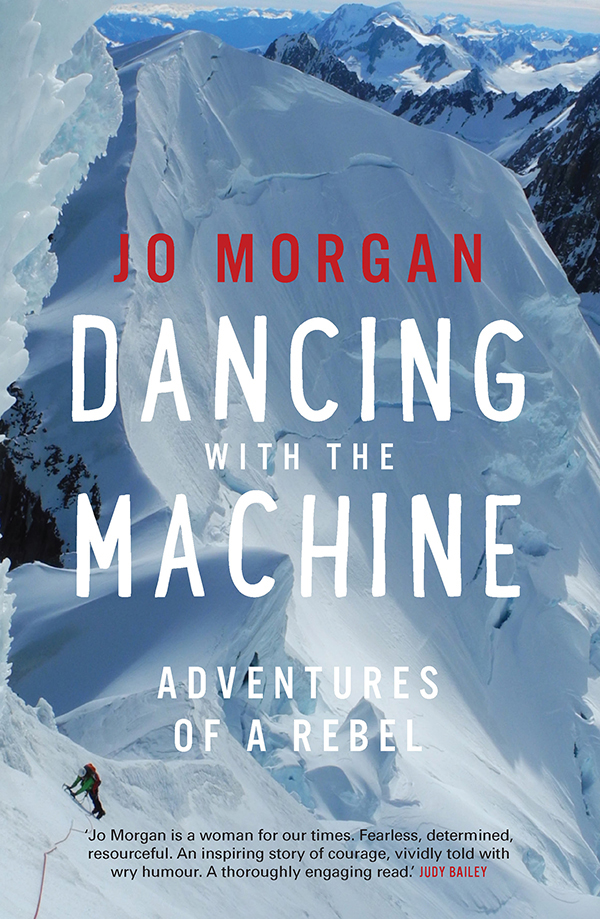

First published in 2022

Copyright Jo Morgan, 2022

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

The cover photographs and the images featured in the picture section are from the authors private collection, unless otherwise credited.

Allen & Unwin

Level 2, 10 College Hill, Freemans Bay

Auckland 1011, New Zealand

Phone: (64 9) 377 3800

Email:

Web: www.allenandunwin.co.nz

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065, Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of New Zealand.

ISBN 978 1 98854 774 9

eISBN 978 1 76106 271 1

Design by Kate Barraclough

To friends and friendship

Live every day

MUSIC.

Swirling, electronic music that makes you think of yoga mats and Lycra. It builds from quiet to semi-loud, but then theres a sigh and a thump and it stops. Theres the sound of a long zipper, the rustle of nylon, and then the wooden floor creaks under Wolfgangs tread. Water gurgles into the kettle and the gas cooker starts with a roar.

What is it with that music? Ive taken Wolfgang to task about it before, and hes been mildly evasive. He liked to wake up to soothing sounds, he said, rather than anything too abrupt. But I suspect its something Tracey has set up for him. It doesnt seem manly enough for Wolfgang.

Shadows dance around the interior of the hut. By now, Martins up, too. Theres the sound of him using the metal pee bucket. I lie in my bag, waiting for my turn. When Martin walks back to the top bunk where his clothes are piled, because Im in the bunk below I cant help but see theres a dark drip mark on the front of his long underwear. Hes not at all self-conscious about it. Once upon a time, I might have shuddered at the intimacy of the cramped space were sharing. Over the years, Ive learned how not to be fully there.

Its my turn on the pee bucket. Its cold out of my sleeping bag. The insides of the windows are feathered with ice from our breath, and now the steam from the kettle and its still pitch-black outside. Its one in the morning, 31 October 2018.

Wolfgang is eating the muesli I made for the trip. Hes emptied a whole bag, and I wonder, not for the first time, how someone can eat so much muesli. I could live for a week on what hes eaten this morning. I help myself to some, and make myself a coffee, whitened with milk powder and sweetened with honey. I sit to eat and Wolfgang casts a critical eye over my bowl.

Eat more, Jo, he says.

I tsk, but add a bit more to my bowl.

After breakfast, we get dressed, layer upon layer. I wear underpants, long johns and overtrousers. I wear three merino layers and a windbreaker. I have inner gloves and gloves. I have a bandanna to keep my hair out of my face and my trusty red beanie under my helmet. I wear thick socks in my climbing boots. I know that after weve been walking for half an hour Ill be taking layers off, but were in for a cold start.

We pack food a few muesli bars each and fill our aluminium bottles with hot water. Martin puts some extra rations in his pack, along with a bit of chocolate for a treat.

One of the last items I pack zipping it into a breast pocket of my jacket is a personal locator beacon. We had a discussion only last night about the importance of keeping these handy. It turned out Martin didnt have one, but I offered him a spare. Now I see without really noticing that he puts it in his pack.

Theres a soft curse in German as Wolfgang checks the battery on the satellite phone and finds it low, even though he charged it only the day before yesterday. I feel a slight pang of guilt. The satphone is mine: its the one that I used to take on motorbike trips. Its getting on a bit, and perhaps its not holding a charge like it used to. I hope we dont need it, because if we do Wolfgang will growl at me.

Wolfgang shrugs and puts it in his pack, along with an extra rope in anticipation of the long abseils well be doing on the way down from the summit. The other rope is out, in readiness for us all to rope up before we set off.

As we leave the hut, Wolfgang in front, Martin next and me on the end of the rope, Martin checks his watch and nods with Teutonic satisfaction.

Two, he says precisely the time we were aiming to leave.

THE WEATHER IS HOLDING. The snowfields are lit by the stars. The night has been cold enough to freeze the surface of the snow into a hard crust, through which your crampons break with each fall of your foot. I notice the consistency of the snow. Its very dry, not the wet, even slushy stuff Im used to.

We climb in an arc, curving round the bad ground at the top of the Sheila Glacier. Even so, there are a few crevasses visible as dark slots in the snow. Im careful to place my feet where the boys place theirs, except where the step is a hole that might well punch clean through to the centre of the earth for all I can see down it. Only then do I make footholes of my own.

After half an hour or so, we pause to shed a layer or two with the mountain looming above us, a jumble of snow and ice fields silvered by the starlight and blackness that is rock faces. My breath is coming a bit short, which is usual for me at the start of a climb. Its a combination of my metabolism slowly getting up to speed, the altitude and a measure of fear. Even now, with over twenty major peaks in the bag, theres always a bit of fear.

We march on, picking our way up a steep slope towards the point where the snow slope meets the face of the mountain. Here, theres a bergschrund, a chasm between the rock and the ice. Yesterdays reconnaissance from the hut suggested that the best route past this difficulty is a snow bridge at the far right of the schrund. Then its the wall. We climbed this same piece of terrain the previous season, when we attempted La Perouse. It was a relatively easy proposition then, because it was covered in consolidated snow that offered firm footing. This year theres very little snow. Instead its jumbled rocks covered with what climbers know as verglas, a very thin coating of ice, barely enough for the points of your crampons to get purchase.

Before we tackle the slope, we stop to adjust the roping. Martin clips on closer to me to give a decent span to Wolfgang, who will lead-climb the wall to put some protection in for us. We watch as he starts across the steep snow bridge, the darkness of the schrund on either side of him. Just before he reaches the end, there is a sharp crack, so loud it makes me jump. He flings his hands over his head and drops along with the shattered bridge into the schrund. The piece of ice he is standing on wedges in the narrow slot and he is buried to his knees by snow pouring in.

For a moment, no one moves or says anything.

If youre OK, Martin says quietly to Wolfgang, then it might be worth trying here.

He points with an axe to a steep, rocky outcrop at the very end of the bergschrund. My spirits plunge as I look where he is indicating. It looks difficult, and I think I might secretly have been hoping that the collapse of the snow bridge would convince Wolfgang that it was too hard to keep trying today. We only have a narrow weather window, and any unnecessary difficulty is going to cut into our safety margin.

But Wolfgang agrees with Martin. He frees himself from the ruins of the snow bridge and then picks his way up to the rock, his headlamp casting a pool of light on the snow.

Next page