Table of Contents

Chapter 1

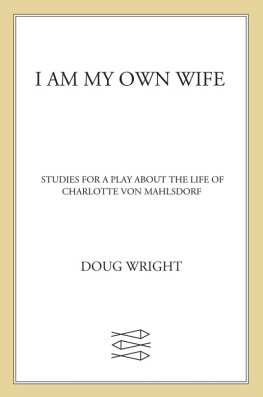

THIRTY SKINHEADS were descending on Mahlsdorf brandishing iron bars, starter pistols, and torn-out fence slats.

I had been looking at the garden from one of the windows of the Grnderzeit Museum. The paper moons we had hung from the clotheslines were tossing in the wind. The eighty or so guests still there were lightheartedly celebrating the coming of spring. The Tina Turner look-alike had already removed her make-up. The belly dancer no longer gyrated for the guests, but was mingling with them at the cocktail bar. Sausages sizzled on the grill. Gays and lesbians were dancing, and the moon shone through the trees of the park like a scene from a kitchy picture postcard.

It was May Day 1991. My co-worker Beate and I had been kept busy the whole evening showing guests from near and far through the museum every half hour. I decided to put out the lights and have a quick look outside.

I had barely extinguished the last lamp when I heard the sharp sound of splintering glass, a noise I have been allergic to for over fifty-four years. A young man, pale as a corpse, burst into the museum, Call the cops!

The Neo-Nazis were flailing away at the guests. Everything was happening with terrific speed. From close range with a flare gun, one particularly brave guy shot my second co-worker Sylvia in the face, right near the eye. A young woman from Munich wasnt so lucky: he managed to hit her eye, badly damaging the retina. Then someone smashed a fence slat over the head of an eighteen-year-old girl.

Screams and groans mixed with the crash of the bandstand being attacked by the rabble and the wrecking of the info-stalls the gay group from East Berlin had erected.

Now the bomber-jackets were storming the dance floor. There, like a lighthouse, stood a transvestite, wearing a fancy dress and a huge red hat. They were going to beat him up, but hesitated, like the cowards they were, because he too had armed himself with a fence slat. Enveloped by a stream of floodlights, he called out to the rabble, Why are you such animals? He said it twice, and suddenly, they stopped and looked at each other in bewilderment. Somebody yelled, Here come the cops! and the young Nazis took off like a stampeding herd of cattle, emptying their ammunition into the neighboring recycling dump. A thousand tons of old paper went up in flames. Everybody was screaming and getting in each others way. The fire brigade drove up with fifty men, put the fire out and took the wounded to the hospitalit was chaos.

I had run out, hatchet in hand. Sylvia and Beate stopped me and told me it was all over. They grabbed me and dragged me back inside. They knew that if I had gotten my hands on someone, I would have hauled off without considering the consequences.

An hour later, I went into the garden with a flashlight. I looked at the wrecked stands, the shattered bottles, the demolished phonograph, and the smashed juke box. As I swept broken glass from the cellar door panes off the road, I was reminded of another scene so very much like this one.

I was on the streetcar going through Mahlsdorf-Sd in the direction of Kpenick. Looking out the window, I saw that Egonas grocery store and the soap shop owned by Wasservogel, the Jew, had both been wrecked. Cohns shop in Kpenick no longer had window panes. The streetcar stopped in the old part of town, right across from a fabric shop. The young owner, tears streaming down her face, was gathering together the remnants of her goods. Three SA men, legs spread apart, were standing by, You Jewish sow, now youre finally gonna learn to work! I was so angry, I clenched my hands around the safety pole. The men kicked the womans hip with their heavy boots. She fell on the broken glass. The trolley went on. By the time I got home from school, all the stores were boarded up. It was the morning of the tenth of November, 1938.

At home, the maid was describing how the Nazis wreaked havoc in other stores owned by Jews. Mr. Brauner, she said to my great-uncle in a voice shaking with anger, you have no idea how Tietzs and Wertheims and Brandmanns shops were wrecked. At Brandmanns, they threw all the big clocks through the display windows out into the street. And the SA men went at the glass cases with their boots and threw the weightsthose heavy weightson top of the dials, and filled their pockets with gold and jewels! What a disgrace!

Could that be true? The firm of Brandmann, famous throughout Berlin, destroyed? I had always listened to their advertisements on the radio with such pleasure. First you heard ding! dong! followed by the ad for Brandmann clocks in Mnzstrasse. My uncle and I had often gone past their shop. How I loved seeing those beautiful clocks in the window!

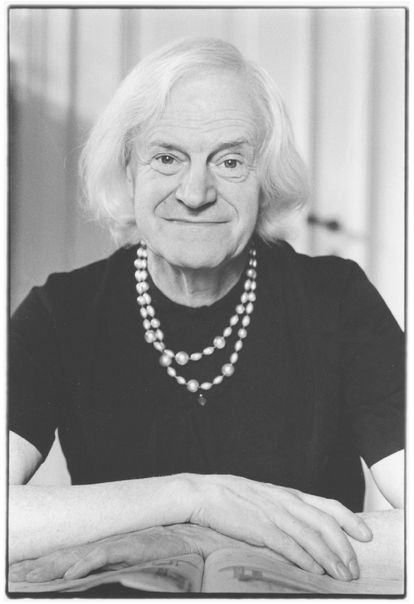

Instinctively, my uncle began to whisper, Emmi, keep all that to yourself, we have to be careful. Who knows whats still to come. Yes, my great-uncle was wise to say that. I owe him a great deal. Ten years before, in Mahlsdorf, a dreamy village at the eastern edge of Berlin, on Sunday, March 18, 1928, I first saw the light of day. I, Lothar Berfelde.

Chapter 2

THE BERFELDE FAMILY is descended from an old Markish aristocratic line first mentioned in a 1285 chronicle as the founders of the village of Berfelde, today called Beerfelde, near Frstenwalde. With the passing centuries, the spelling of our name changed from Berfelde to Beerfeld, Baerfelde, Berfeldt, and finally, Beerfeldt. The family crest, however, remained unchanged: a shield divided in the center, with one star against a blue background, the other against a silver one.

My genealogy resulted from a misalliance in the middle of the eighteenth century. One of my ancestors, an officer in the Prussian army, had married the daughter of a fisherman, something simply not done at the time. As dimmed nobility, we kept our crest, but lost our von.

The descendants of the aristocratic branch of the von Beerfelde line, to whom Im only distantly related, were in possession of the castle and manor house Zuchen near Zanow, in the area of Kslin in Pomerania, until 1907.

Bertha von Beerfelde, the head of this family and mother of nine children, had a hard time of it. Her husband, Rittmeister Rudolf von Beerfelde, a Schwedter dragoon, was thrown and crushed by his horse during maneuvers. After a fire in 1905, followed by loss of livestock and bad crops the next year, Bertha von Beerfelde decided to sell her holdings and to divide the proceeds among her nine children. The buyer, a mill-owner from Zanow, brought the money in cashtwo and a half million goldmarks! Mother and children, buyer, and the messengers with the money were all seated in the ballroom of the palace. The forester had also been invited. He stood with loaded gun at the ready in case something should go wrong.

Two-hundred and fifty thousand goldmarks each, dealt out by the accountants, were placed on the table in front of every one of the nine children, as well as the mother. Then she stood up and said, Be frugal and increase your share.

One of her sons, a captain in the Alexander regiment and a Prussian Officer, Hans-Georg von Beerfelde, filled with burning patriotism and love for the Kaiser, had enlisted in the First World War. Courageous and fanatically devoted to truth, he saw the light after a few years when that hopeless war, getting more and more hopeless each day, was taken over by Hindenburg, the hero of Tannenberg, and the power-serving First Quartermaster General Ludendorff.