Advance Praise

With sensitivity, love, and humor, Emanuel Rosen tells the story of his Yekke grandparents, their immigration and difficulties in the homeland of the Jewish people, and their journey in search of their roots and identity in Germany. An important and fascinating book that awakened in me deep feelings and a longing for a generation that is no more.

Gabriela Shalev: former Israels Ambassador to the U.N.; Professor (Emeritus) the Hebrew University of Jerusalem

I thought Id take a quick look at this book, but then I kept reading all of it in a day and a half.

W. Michael Blumenthal: Former U.S. Secretary of the Treasury and director of the Jewish Museum Berlin (1997-2014)

From generation to generation, it becomes more difficult to write about the persecution of Jews before and during WWII as ones personal past. Too much has been lost, and precisely because of that one wants to write about what can still be found. I respect what Emanuel Rosen did in this book, patiently and carefully exploring the past and guiding us through his findings about the story of his family.

Bernhard Schlink: Author of The Reader

This is a gripping and engaging exploration of a family whose lives were indelibly changed by Nazi restrictions, by immigrant life in Israel, and by a grandsons search for missing parts of the stories.

Martha Minow: Harvard Law School

The mystery of why Emanuel Rosens grandfather killed himself haunts this book and keeps the reader gripped until the secrets of the past are ultimately uncovered and revealed. Suicide leaves a legacy of silence for those of us who are left behind and works such as this allows us to begin to understand how we are affected and start to heal. This book will greatly help survivors of suicide loss on their own personal journeys of discovery and hope.

Carla Fine: Author of No Time to Say Goodbye: Surviving the Suicide of a Loved One

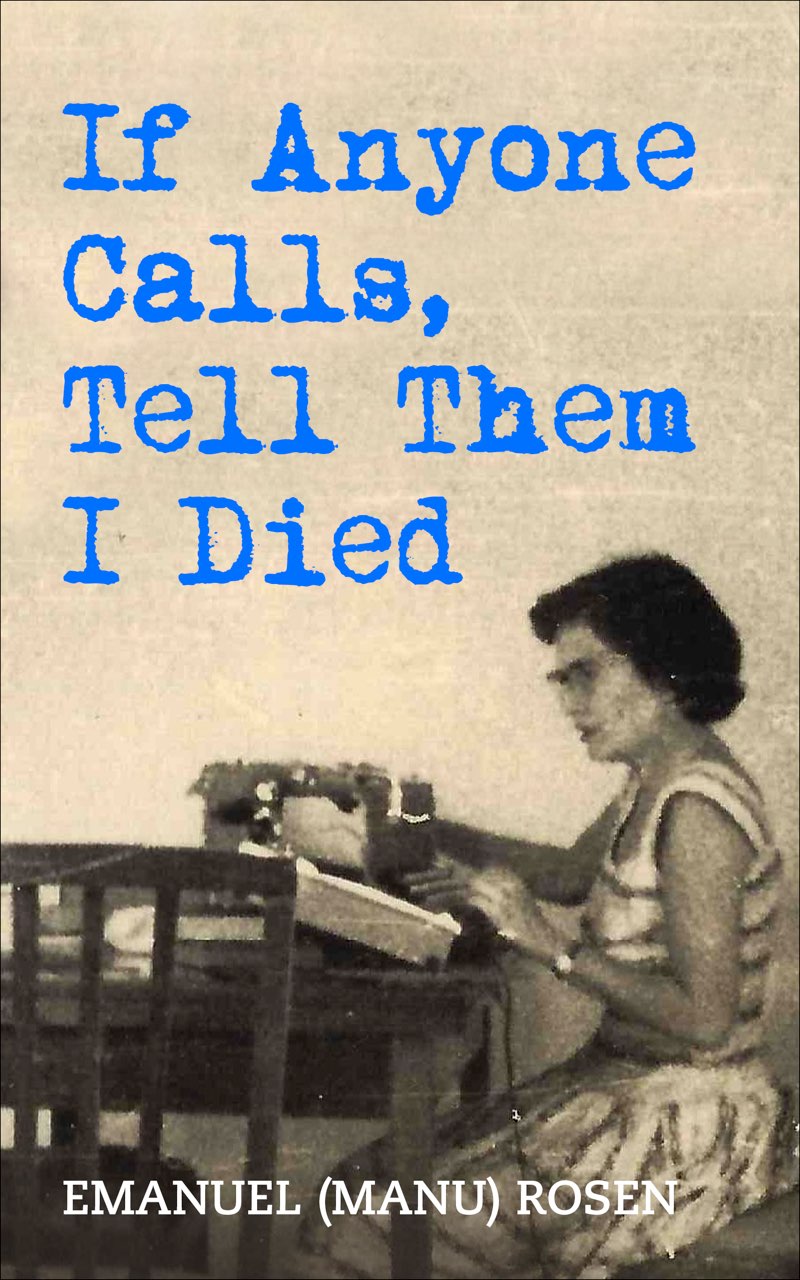

If Anyone Calls, Tell Them I Died

A Memoir

Emanuel (Manu) Rosen

ISBN: 9789493231146 (ebook)

ISBN: 9789493231139 (paperback)

ISBN: 9789493231283 (hardcover)

Cover: Mirjam Rosen typing at home in summer 1957.

Copyright 2021 Emanuel (Manu) Rosen

Publisher: Amsterdam Publishers

info@amsterdampublishers.com

If Anyone Calls, Tell Them I Died. A Memoir, is Book 9 of the Series: Holocaust Survivor True Stories WWII

All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any other information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Contents

To immigrants and the uprooted

Tel Aviv

Its not funny to me.

My mom hardly ever told a joke, but she had one-liners ready for any occasion. If you told her that somebody was getting married, she would shoot back, Against whom? Before she would take her afternoon nap, she would order, If anyone calls, tell them I died. If we saw an ugly piece of art in a shopping window, she would warn my sister and me, If you dont behave, Ill buy this one for you! And if she talked about us with a neighbor or a relative, she would sum it up, Theyre good kids. And after a well-timed two-second pause shed add, Especially when theyre asleep.

As opposed to her pre-packaged humor, I loved telling new jokes, and growing up, she participatedpatiently, I should sayin the different phases of joke telling I experimented with. When I was a teenager in the 1960s, my friends and I were obsessed for a while with what we called horror jokes, and I would get special pleasure telling these jokes to my mom because of the mix of laughter and moaning they would invoke in her. Jokes such as Did you hear about the blind man who bled to death trying to read a cheese grater? She would put her hands over her glasses, shake her head, and say, This is awful! or Enough! But she would still be laughing.

One day, another boy at school told me a new joke, You know that falling from a tall building wont kill you?

This sounded promising. I waited for the punch line.

Its the contact with the sidewalk that does the trick.

I thought it was hilarious. Back from school, I couldnt wait to tell my mom the new joke. When I heard her car approaching, I waited for her in the hall, a pretentious name for the little corridor that connected the three rooms of the house. When she came in, I told her I had a new joke, You know that falling from a tall building wont kill you?

My mom froze. Her lips twitched for a second, and her grey eyes didnt move.

Its the contact with the sidewalk that does the trick.

She turned away. Its not funny, she said, her gaze fixated on the blue armchair by the phone.

I insisted that it was a funny joke. A very funny joke. How couldnt she see that it was funny?

Its not funny to me.

Menlo Park

This is not for the car.

I found a bunch of letters in an old box that I had brought from my moms house in Tel Aviv after she had died. A bunch of letters that had survived decades of clean-ups had to be important, but between my poor German and the old-fashioned handwriting they were written in, I couldnt figure out why. Now I was a man with a family, older than my mom was when I was a stupid teenager. I was busy living life, yet once in a while, I would open up that box and give it another try. Something pulled me to these letters that held the answer to a question I didnt know I had.

They were written by my grandparents, Dr. Hugo Mendel, whom we called Opa (grandpa in German) and Lucie Mendel, whom we called Oma (grandma), on a trip they had taken to Germany in 1956, and most were addressed to Mirjam or Mirjmchen, a term of endearment they used to call my mom. And then one day, the question that these letters could answer became clear. My grandparents separated after that trip, and I realized that these letters could explain why. By separated, I dont mean that they divorced but that each went his and her own way. My grandma decided to live, and my grandpa decided to die.

Their return to Israel from this trip to Germany is one of my first memories. It was in October 1956, I was three and a half, and I remember standing by the table we called the short table, which at the time stood at my eye level. Except for the table itself, I remember two things: A few blurred figures in the background and one present they had brought back from Germanya green bath sponge in the shape of an elephant. I dont think Ive ever been happier with a present. It thrilled me beyond measurea sponge thats also an elephant! In Tel Aviv of the 1950s, things did not tend to be in the shape of other thingsa sponge was a sponge, and an elephant was an elephant, and suddenly this? I vaguely remember the blurred figures laughing at my uncontrolled excitement.