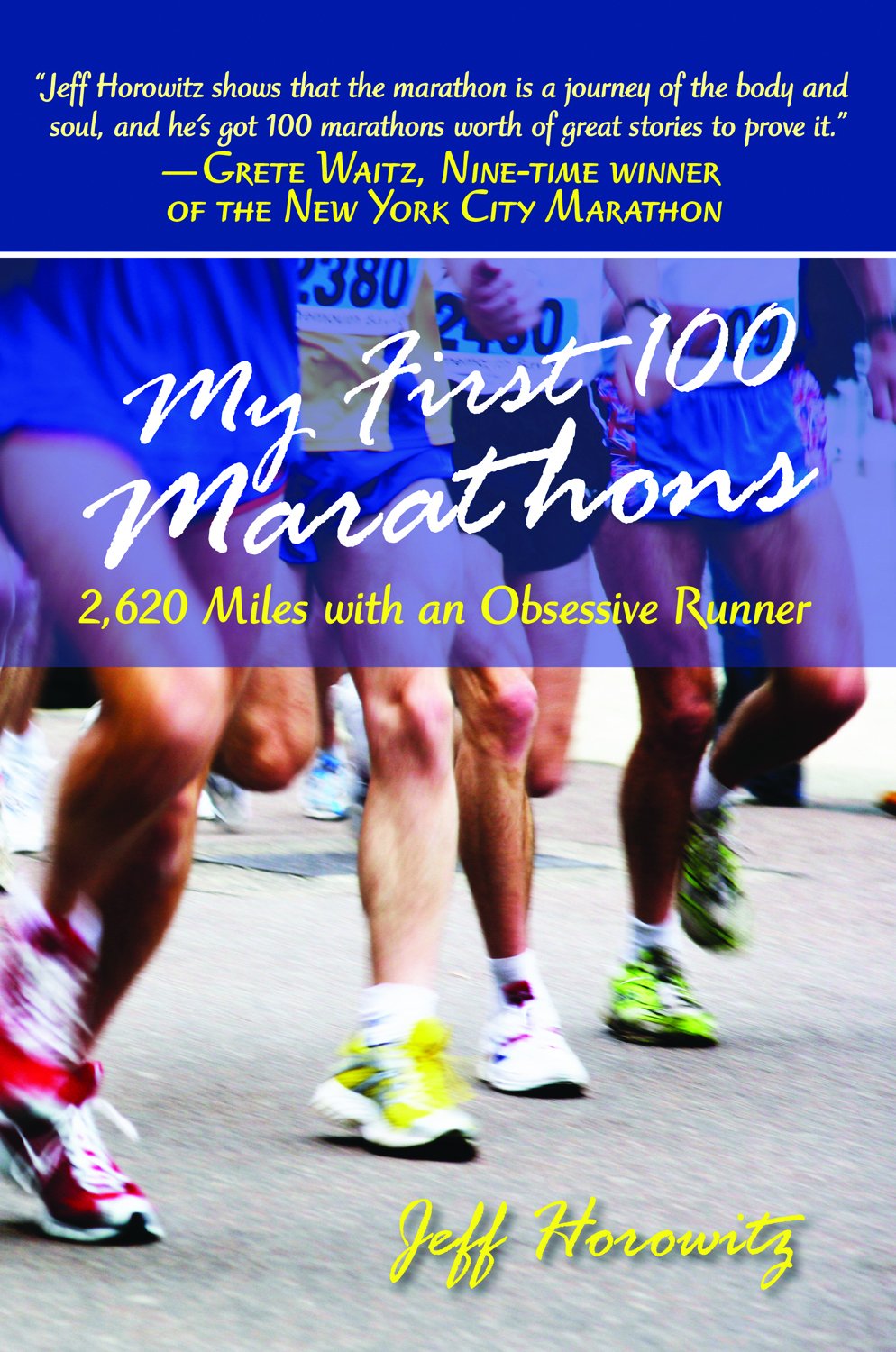

JEFF HOROWITZ is a certified personal trainer and running coach, living in Washington, D.C. He got hooked on marathoning in 1987, and in addition to his own running, he has coached hundreds of others to run their first marathon while raising money for various charities. When hes not busy doing these things, hes also an attorney, columnist, husband, and father to little Alex Michael, who pleased his daddy by quickly learning how to say, Look, Im running! Visit Jeff at www.runtothefinishline.com .

Epilogue: Bumps in the Endless Road

I n November 2004, a story was reported in the back pages of The New York Times that was of great interest to me. Dr. Dennis M. Bramble of the University of Utah and Dr. Daniel E. Lieberman of Harvard had published a paper hypothesizing that ancient humans were physiologically predisposed to be long-distance runners.

The scientists had begun by analyzing the evolution of our physique. As early as two million years ago, humans developed an upright posture, long legs, shorter arms and a narrower ribcage and pelvis. We also lost our fur, which allowed us to develop sweat glands and prevent overheating during intense exertion. We developed a ligament network to keep our heads steady while running, and a muscle and tendon network along the back of our legs, including an Achilles tendon, to store and release great amounts of energyenough to propel our bodies forward quickly with power. And then theres our highly-developed backside, which stabilizes our midsection during running.

All of these traits are conducive not just to walking, but to long distance running, and apes dont share any of them. Bramble and Lieberman speculated that running would have increased the early humans chances of survival, as they could cover large areas of African grassland in pursuit of food.

Apparently, then, we are all born to run.

Of course, I knew that already. I was once told that theres a German word, tatesfruedig, which roughly means the joy of doing that which you can do well. A cheetah loves to sprint because it is built to sprint, and a monkey loves to climb because it is built to climb. My running wasnt an aberration; it was an expression of my genetic heritage. It was something I was born to do.

So I kept on running. I ran marathons in Montana, Alaska, and North Dakota. In late September, with the birth of my son just days away, I returned to the Marine Corps Marathon yet again. And then, on November 12, 2005, I experienced something more miraculous than a marathon finish line: the birth of Alex Michael, named in honor of my grandfather and Stephanies dad. I cut his umbilical cord and then later laid my hand across his tiny body. There was no amount of thinking that could compare to the reality I saw before me. It was magical and humbling. I thought about my life, and I felt like I was the luckiest man on earth.

Then things became unhinged. A dear friend of twenty years died of breast cancer. A cousin died from lung cancer. And then hardest of all, I had to watch my mothers health suddenly spiral downward, despite all the treatments recommended by the best doctors we could find. Mom was obese and had diabetes, which I knew was a time bomb waiting to explode, but there was little I could do about it. As a coach and trainer, I felt particularly responsible, but I couldnt force her to save her own life, and after a while, I decided not to spend whatever time we had left together fighting with her over this. But now her problems gained a velocity I never could have imagined: she experienced full renal failure and had to go on dialysis, then she contracted pneumonia twice and a vicious intestinal infection. Fear and various drugs addled her mind, and a foot infection forced her doctors to amputate her leg. The lone bright spot for us was the look on her face when she held tiny Alex in her arms for the first time.

Her health continued to decline. Every time the phone rang, I feared the worst. My sisters and I shuttled Mom between hospitals and nursing homes, and we realized at some point that she would never return to her old apartment. We were still hopeful of her recovery, and had just filed the paperwork to move her into a home that could properly care for her. My sister Marlene was visiting us in D.C. with her two children when we got the phone call from New York. Moms blood pressure had suddenly plummeted, and she had needed to be resuscitated twice. She now had a tube snaking down her throat, delivering oxygen, and her heart was beating only because she was being fed drugs intravenously. Her doctors wanted to know if we wanted to give them the order to stop resuscitating her. They wanted to know if we were ready to let her die.

Marlene had been on a grand tour of Europe and Asia when Dad fell ill. When she called us from Istanbul, we told her not to worry, but that she should sit still for a while and keep in touch. There was no need to panic, after all. Everything would be okay. And then Dad suddenly died, as you know. Marlene immediately got on a plane heading home, and spent that twelve-hour flight weeping and growing the guilt she would carry forever for not being home when her daddy passed away.

As I looked at Marlene now, I knew that more than anything else, I didnt want Mom to pass away without Marlene being at her bedside. So the answer was no. We would not give a do-not-resuscitate order. We told the doctors to keep the meds flowing. We were on our way.

When we reached the hospital, Stephanie took Alex and Marlenes children back to Marlenes house, where Marlenes husband Jerry was waiting for them. Marlene and I went up to Moms room in intensive care. Our sister Dori was already there, with red-rimmed eyes. She had been there for hours.

We went right to Moms bedside. She looked back at us, wide-eyed, gasping for air as a tube hung from her mouth. Her gaze shifted, and I realized that she was looking back and forth across the room. Back and forth, again and again. I wondered if she knew we were there.

We stepped into the hall to speak with the doctors on call. They told us that the only thing keeping Mom alive was the medication they were pumping into her veins to maintain her blood pressure and heartbeat. Moms body had already begun to shut down; the flow of blood to her remaining leg had virtually stopped. After absorbing this information, we returned to her room. I pulled back the blanket and looked at her right leg. Her foot was already turning black.