1995 by Sam Wellman

Print ISBN 978-1-61626-905-0

eBook Editions:

Adobe Digital Edition (.epub) 978-1-62029-648-6

Kindle and MobiPocket Edition (.prc) 978-1-62029-647-9

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted for commercial purposes, except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without written permission of the publisher.

Churches and other noncommercial interests may reproduce portions of this book without the express written permission of Barbour Publishing, provided that the text does not exceed 500 words and that the text is not material quoted from another publisher. When reproducing text from this book, include the following credit line: From Corrie ten Boom, published by Barbour Publishing, Inc. Used by permission.

Material from the following books used by permission of Fleming H. Revell, a division of Baker Book House: Corrie ten Boom, In My Fathers House 1976; Carole C. Carlson, Corrie ten Boom: Her Life, Her Faith 1983; Corrie ten Boom, Father ten Boom 1978; Corrie ten Boom, Prison Letters 1978.

All scripture quotations are taken from the King James Version of the Bible.

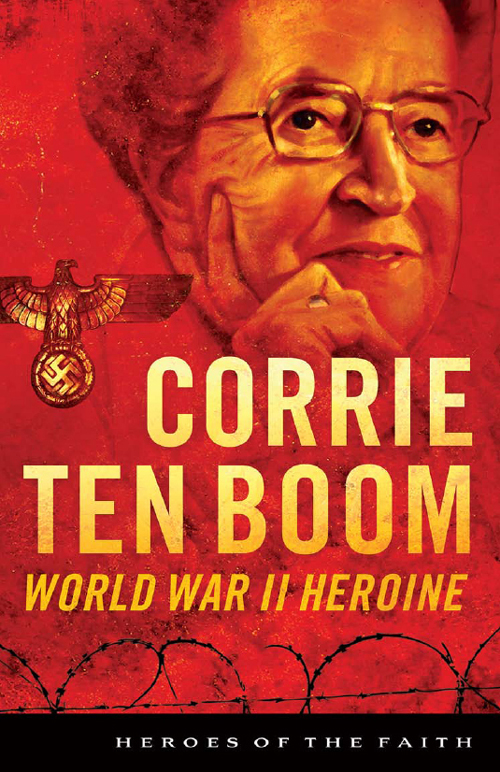

Cover illustration: Greg Copeland

Cover design: Kirk DouPonce

Published by Barbour Publishing, Inc., P.O. Box 719, Uhrichsville, Ohio 44683, www.barbourbooks.com

Our mission is to publish and distribute inspirational products offering exceptional value and biblical encouragement to the masses.

Printed in the United States of America.

CONTENTS

1.

JESUS IS HERE

The vaporizer on the small alcohol stove spewed a fog of camphor and water into the air of the dark bedroom. The vapor settled over Corrie ten Boom, who clutched a blanket over herself on a bed. Aches shadowed every movement of her body.

Dear Jesus, she prayed, let this pass.

Corrie ten Boom felt her years. It seemed as if until today she had never stopped long enough in all her fifty-two years to let age catch up with her. But more than age caught up with her today. Her prayer was a plea for many things to pass. Jesus had been in her heart for a very long time, and she hoped her fear was just momentary, just another unpleasant symptom of the flu.

But everything has gone wrong lately, she muttered.

It seemed everyone in Holland must know the ten Booms were hiding fugitives in their house. After all, it was 1944. Holland had been infested by German soldiers for four years. The worst of all the Germans were the slithery Gestapo, the secret police of the Nazis. The ten Booms had been hiding Jews and Dutch boys in their house for two years. They never had less than seven fugitives living with them these desperate days. How much longer could their secret last before the dreaded Gestapo bashed on their door? The Gestapo struck at night like vipers. Their victims were groggy, unpreparedlike Corrie felt now.

THE GESTAPO STRUCK AT NIGHT LIKE VIPERS.

Is it night or day? She tried to focus her eyes.

She had slept in this very same bedroom in this very same house as long as she could remember. Her home was precious to her. The past was so wonderful that thinking about it softened her pain. Her thoughts drifted back.

Yes. As far back as she could remember her home was gezellig, close and warm and cozysmelling of soup and fresh bread, and sounding of soft laughter and the rustles of Mama and three aunts in long dresses. A five-year-old like Corrie could have a wonderful party with her doll Casperina under the dining room table. She could even creep down the steps into Papas workroom behind his shop that faced Barteljorisstraat. Silently she sat and smelled his cigar and listened to clocks ticking and tocking like hundreds of heartbeats. She watched bearded Papa bent over his bench. Each time he placed some tiny thing in a watch he would pause and say, Thank You, Lord, as gently as if he were talking to Corrie or Mama. That was Papa. God must have been right there with him.

Still, as gezellig as the home was, there were limits on the quantities of sound and activity that were correct and proper for a Dutch home in 1897. And to be allowed to explode beyond those limits, five-year-old Corrie had to play outside in the narrow alley. Her aunts with their tight-bunned hair seemed very happy when she asked for permission to play outside before she dashed into the alley. But Mama was not so happy.

Except on her sick days Mamas great wide blue eyes would appear in the dining room window again and again to check on her. Aunt Bep called Corrie the baby of the family. Corrie heard her say that while she was playing with Casperina under the table one day. Corrie didnt like to be called a baby. If another baby would just arrive she wouldnt be the baby any more. Aunt Anna had told her that when a baby is too small and weak to live in the cold world there is a special place under the mothers heart where the baby is warm and can grow. Thats where Mama carried Corrie. Now if Mama would just carry another baby there Corrie would no longer be the baby.

Out in the alley, Corrie was not a baby. She was just one of many children who played there. Except for the town square and streets, which were bricked solid and overrun with grownups, there was little other open space in downtown Haarlem. The alleys were not much more than sun-starved slits among tall buildings, but they did have precious space. And they werent dangerous like the streets. It was rare for a wagon or a rider to intrude into the alley.

And who cant hear wheels rumbling or a horse clopping up the potholed alley anyway? reasoned Corries papa with worried Mama.

Corrie skipped rope by herself on her sturdy legs or joined the other children to play bowl-the-hoop or a game with a ball and stones called bikkelen. Even blue-skinned Sammy was out there almost every day, bundled up and slumped in a wheelchair. It was hard to include him in much more than an occasional game of tag, when he was home base. Sammys moment came when Corries sister Nolliethe moedertje, the little mothercame home from school. She would start to play with the other children but in no time at all she was pushing Sammys wheelchair, mothering him.

Nollies return expanded Corries world. Corrie would cry, Lets go to the square!

While Sammy slumped even more in his wheelchair and began grumbling about potholes rattling his bones, Nollie would go inside to get permission to go to the square with Corrie. The two sisters would hold hands and hurry down the alley. On Barteljorisstraat, horses pulled trolley cars, clanging toward the town square only half a block distant. From the square itself, rich bells bonged and pealed. They would whisk down the narrow sidewalk past tall, dark brick buildings until Corrie saw the gothic spire of Saint Bavos towering over the square. The girls would find a bench and watch grownups strolling through the square or hurrying to their trolley.

Who is Laurens Coster again? Corrie would ask Nollie.

Nollie would glance at the statue that held center stage in the square.

Laurens Coster was a Haarlemite who invented the printing press. Pay no mind to what ignorant people say about some German called Gutenberg. Nollies face had that special hardheaded look of the Dutch: