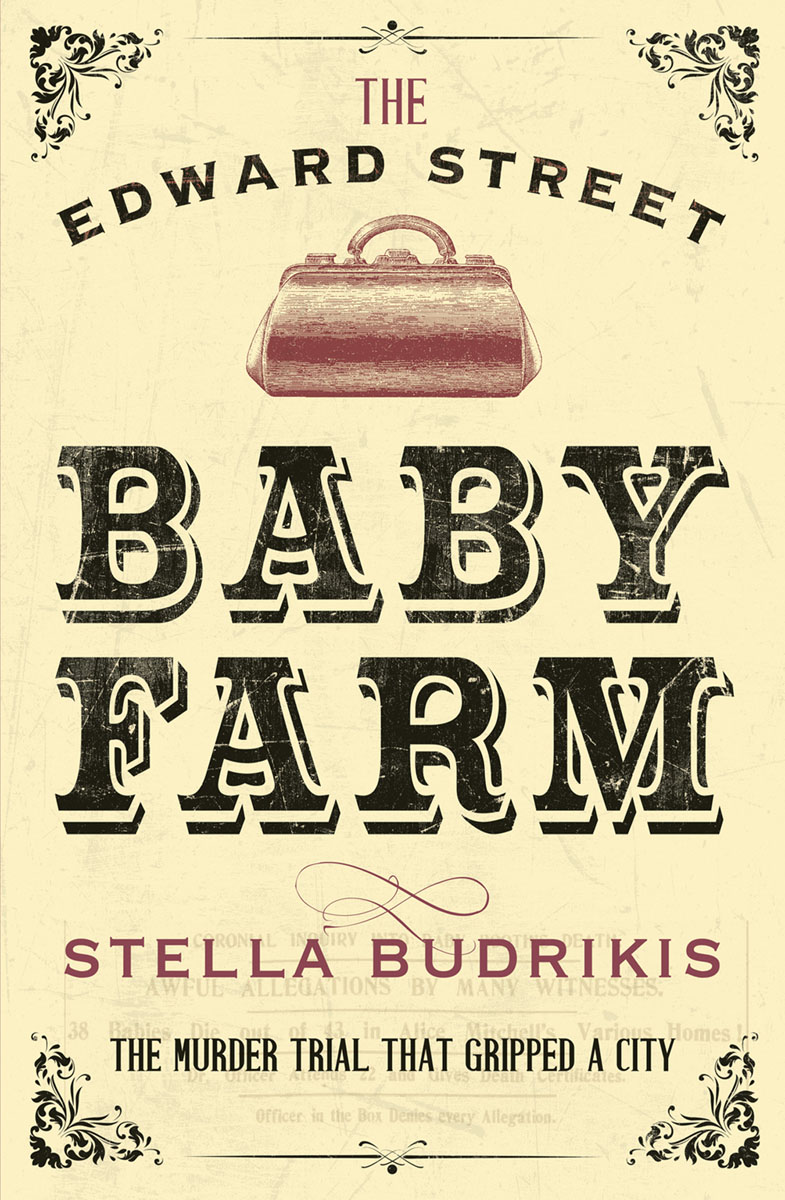

First published 2020 by

FREMANTLE PRESS

Fremantle Press Inc. trading as Fremantle Press

25 Quarry Street, Fremantle WA 6160

(PO Box 158, North Fremantle WA 6159)

www.fremantlepress.com.au

Copyright Stella Budrikis, 2020

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Enquiries should be made to the publisher.

Cover images: www.shutterstock.com: Channarong Pherngjanda, mashakotcur, Ensuper

Back cover: SLWA image b4576512_1:042144PD: Perth Supreme Court, ca.1910

Printed by McPhersons Printing, Victoria, Australia.

ISBN 9781925816099 (paperback)

ISBN 9781925816105 (ebook)

Fremantle Press is supported by the State Government through the Department of Local Government, Sport and Cultural Industries.

Publication of this title was assisted by the Commonwealth Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body.

Stella Budrikis was born in England but has lived in Western Australia for most of her life. She has worked as a general practitioner, addictions clinic doctor, pastoral carer and freelance writer. Stella is married with two grown-up daughters.

For Zoe and Amy

who inspire me

Contents

Introduction

Baby farmer seems a strange combination of words to our ears, but it was an all-too-familiar expression for our Victorian and early twentieth century forbears.

I first came across the phrase in a South Australian newspaper from the 1870s. At the time, I was writing a book about Susan Mason, a young woman from Adelaide, who was unmarried when she gave birth to her first child in 1868. I wanted to know what happened to the children of single mothers like her in that era.

The newspaper article described a court case in Adelaide in which a woman was charged with the murder of a seven-month-old boy. He had been left in the womans care by his mother for a fee of eight shillings per week. The child had been dreadfully neglected by the foster mother, a single mother herself with several other malnourished infants in her care. The newspaper described her as a baby farmer.

The case wasnt directly relevant to what I was writingSusan seems to have handed her own child over to a family member or friendbut the phrase baby farmer stuck in my mind. After Id finished writing the book, I googled baby farming, more out of curiosity than with any intention of writing about the topic.

A baby farmer, I learned, was a pejorative term for someone who took in infants of single mothers, and other unfortunate families, for a weekly fee or lump sum, with little or no concern for the babies welfare. As Id already discovered, baby farmers sometimes came to the notice of the police when a child died in suspicious circumstances.

I was startled to read that one of Australias most notorious baby farmers, Alice Mitchell, was tried for the murder of a child in Perth, in 1907. Thirty-seven infants were thought to have died in her care. Ive lived in Western Australia for most of my life. The houses in which Alice Mitchell carried on her business are within walking distance of my own home. Yet Id never heard anything about the case before. (As Ive since discovered, the Old Court House Law Museum in Perth has a display about the Alice Mitchell case. But few people know that the museum exists.)

On Trove, the National Library of Australias website, I soon found a plethora of newspaper articles about the trial and the coroners inquest that preceded it. The case had been headline news for weeks. The story of Alice Mitchell and her baby farm also featured as a chapter in a couple of true crime books and appeared in articles on several websites. I thought the trial would make a good topic for a blog post; there seemed too little substance to the story to write a whole book about it, especially if I wanted to avoid focusing on the sensational and the morbid.

But a few aspects of the case still puzzled me. The names of two key witnesses, Miss Lenihan and Dr Officer, appeared repeatedly in the newspaper articles Id been reading. Harriet Lenihan, Perths first lady health inspector, was held responsible for having failed to ensure that deaths of children in Alice Mitchells care were reported to the relevant authorities. Dr Ned Officer, a specialist in childrens illnesses, had signed a large proportion of their death certificates, without raising any alarm.

How was it that socially conservative Perth had a female health inspector in the early 1900s? Where did she come from? What happened to her after the trial? What were Doctor Officers qualifications and how did he get away with what seemed like gross negligence?

With just a little digging online, I discovered that Miss Lenihan and Dr Officer both had interesting and unexpected past careers that had not been mentioned in the newspapers during the trial. Nor had the more reputable newspapers discussed Alice Mitchells family background and personal history, perhaps for legal reasons.

It took rather more digging, including several visits to the State Records Office, to find out what happened to Alice Mitchell, Harriet Lenihan and Dr Officer after the 1907 trial, but that too proved to be intriguing.

Ive always been fascinated by the way peoples lives intersect, bringing all their past experiences and personalities crashing together at a single place and time, before diverging again like billiard balls on a table. Here were three people, one from Perth, one from Victoria and one from Ireland, whose paths crossed in Perth in 1901, with disastrous results for two of them and devastating consequences for dozens of young lives.

But apart from the histories of the three main actors, I was also intrigued by what I was learning about Perth in the early 1900s. In 1901, the year Western Australia joined the Australian Federation, Perth was still a small colonial town. Conditions in the city were primitive, with few paved streets, no sewage system and regular outbreaks of typhoid and bubonic plague. The infant mortality rate was staggeringly high by )

A clique of families, whose forebears had been among the first settlers, wielded enormous influence, socially and politically. Women, despite having won the vote and found their way into some of the professions, still proved their worth by marrying and raising a family. Single mothers were considered fallen women, with no moral right to raise their own children. The states indigenous inhabitants led state-regulated lives with no say over what happened on their own land.

During the trial, the press documented the outraged and sometimes hypocritical response of the public to the dreadful revelations coming from the courtroom. Here was a society struggling to lay the blame for its own failings upon an individual to appease its conscience. But as I read their reports, it seemed to me that the newspapers and their editors were themselves players in the whole affair.

Next page