A VERY SPECIAL THANK you to Margarets great friend Damaris Hayman, for sharing her memories with me.

I am much indebted to Rod Clare, Kelly Wooten and Richenel Ansano, Special Collections, Duke University, Malcolm Troup, Adrian Brown, Trish Hayes (BBC Written Archive Centre, Caversham Park, Reading), Mark Cardale, Mark Stevens, Senior Archivist, Berkshire Record Office, Kelly Jones (Wimbledon High School) and Mark Whiston. Their encouragement and enthusiastic participation have provided me with a wealth of information.

I am also grateful to the late Ken Annakin, Elroy Ashmore, the late Frith Banbury, Keith Baxter, David Benn, Melissa Benn, Tony Benn, Bradley Bolke, Celia Bannerman, Claire Bloom, Richard Briers, Peter Brook, Adrian Brown, Jess Campbell, Scott Carpenter, Petula Clark, Anna Evans (Chichester Festival Theatre), Irene Garland (Anglo-Norse Society) Geoffrey Green, Noel Hess, James Hogg, Mark Jones, Tessa Kulik, Ruth Leon, Roger Lewis, Philip Lowrie, Anna Massey, Francis Matthews, Virginia McKenna, Michael Noakes, Judy Parfitt, Nicholas Parsons, Muriel Pavlow, Ian Payne, Dan Peat, Josette Portelli (Manoel Theatre), Robert Ross, Rosy Runciman (Archivist, Cameron Mackintosh Ltd), Peter Sallis, Lyn Scrimshaw, Shirley Segal, Donald Sinden, Nina Soufy, John Standing, Sarah Stead, Clive Swift, Antony Worrall Thompson, Angela Thorne, Alan Travis, John Stuart-Webb, Benjamin Whitrow and Terry Young.

Thanks to the Staff at the V&A Theatre Archive, the BFI National Archive, Kristy Davis, Archive Officer, Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection, Gerry McArdle, Historical Disclosures, Army Personnel Centre and Sandra, Hilary and Lai-ming at Alexandra Park Library.

A particular mention must go to Daniel Merriman for his various contributions to the book and much appreciation to all the Merriman clan for allowing Miss Rutherford to join our household for a year.

Last, to Graham Coster, Dan Steward and Lydia Harley for their help and guidance.

CONTENTS

A LTHOUGH YOUVE NEVER tried to be a glamour girl, breathy BBC journalist Wendy Jones asked Margaret Rutherford in a radio interview in 1964, would you say your face is your fortune?

After a beat Rutherfords timing was always impeccable the actress replied, Oh well yes I suppose I have to admit that my five chins may have something to do with it, and all the wrinkles that I have.

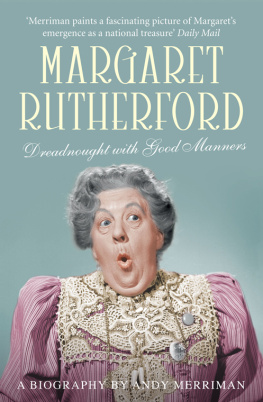

It was, of course, her physiognomy and startling physicality that always drew attention to her performances. Indeed, no character actress has generated such an outpouring of descriptive pronouncements. It seems that Margaret Rutherfords very appearance gave journalists and critics licence to unleash unfettered metaphors and similes: she was depicted variously as a spaniel-jowled actress, a splendidly padded windmill, a dreadnought with good manners and a glorious galleon in full sail firing salvos at all who crossed her bow. One critic was even quoted as saying, If you hung the face of Margaret Rutherford on the side of the Notre Dame Cathedral she would make all the other gargoyles look like Audrey Hepburn. It is quite the ugliest old ragbag of a face you have ever seen.

Rutherford herself was philosophical about the looks that the Good Lord had bestowed on her: If you have a face like mine, the thing is to learn to live with it and come to terms with it. This, I think, I have managed, and it has, after all, been rather good to me. The Americans called my face an English muffin. Its true the nose is rather insignificant, one half of my mouth does not seem to work and would benefit by a little stretching; the lips have little body to them.

A glamour girl she wasnt. A great actress she was.

Although Margaret Rutherford didnt make her first professional appearance until she was 33 and had to wait for nearly a decade for her West End debut in Hervey House at His Majestys Theatre, Haymarket, like vintage champagne, when finally uncorked she came fizzing out of the bottle effervescent and inebriating.

She subsequently graced the theatre and the silver screen for over thirty years, and remains one of Britains most popular actresses. She appeared in over forty films and was the highest earning British actress at MGM. In the late 1950s, she was voted one of the top ten box office stars of all time by the Motion Picture Herald Fame Poll, and in 1963 was awarded an Oscar for her role as supporting actress in The VIPs. She was much loved as Agatha Christies famous sleuth, Miss Marple, in a quartet of films in the 1960s. It is also providential that she reprised on film a number of her celebrated stage appearances, which have thus been saved for posterity: her performances in Aunt Clara, The Happiest Days of Your Life, The Importance of Being Earnest and, of course, perhaps her most celebrated incarnation, as Madam Arcati in Blithe Spirit.

Margaret Rutherfords appeal has always been universal, as friend and writer Eric Keown recognised half a century ago: Most well known actresses fan a glow in only a particular section of the community. Some seem born to be the pin-up girls of the fifth-form study and it is easy to think of some clearly destined for the walls of the cavalry mess, and again of others whose natural gallery, if anywhere, would be the library of the Athenaeum. But Margaret Rutherfords gently rugged features know no vetoes. She appeals to all ages. Her comic genius dissolves elder statesmen and barrow boys, lorgnetted dowagers and the sternest critics in pretty frocks.

She was formidable and yet sympathetic, fierce and yet human, and her background in elocution imbued the delivery of her dialogue with meticulousness and zest. She had the capacity in her repertoire for taking the character to its limit without overdoing it, and always used great judgement and consideration in tackling a part.

The drama critic and journalist J.C. Trewin remarked, When you have seen any performance by Margaret Rutherford you are certain to remember it. Those penetrating eyes, that quick, spring-heeled voice, remain in mind. She is, in the best sense of the word, an attacking comedienne, one with a flash bulb effect. Immediately she appears you realise that she has the gift, so vital to an actress, of establishing her character at once; there is no need for her to mess about, to play herself in.

Inevitably Rutherford wished to be an actress in the grand tradition. How I would love to have been a great traditional actress like Bernhardt, Duse or Ellen Terry. There have been so many parts I yearned to play there is a twinge of regret that I was typed for scatty types so often and therefore have not had the chance to tackle some of the serious major roles that I would have liked. And yet acting for her could be a wondrous divertissement: All I wish to do is to take a back seat, to retire behind the personality of the part I am playing. There is a wonderful escapism in acting. When you are sick of yourself or of the futilities of life, it is marvellously refreshing to partake of the nature and life-blood of another being and forget yourself completely.

And there was, indeed, much in her personal life from which to escape. Throughout her life, Margaret Rutherford was haunted by the spectre of mental illness, the suicide of her mother and a murder in her family which was kept secret. Hers was an existence shrouded in mystery and deceit. Rutherford herself suffered from manic depression nowadays known as bipolar disorder which at different times necessitated medication, institutionalisation and electroconvulsive therapy. She required regular rest cures from her self-diagnosed bouts of melancholia. Invariably she would recover temporarily, and to paraphrase one of her favourite creations, Miss Muriel Whitchurch in The Happiest Days of Your Life, take stock, and then into the fray like giant refreshed.