CONTENTS

Guide

Raised in Northern Arizona, Samuel K. Dolan is an Emmy Award-winning documentary producer and has produced dozens of programs for History Channel, National Geographic and other networks. He is the author of Cowboys and Gangsters: Stories of an Untamed Southwest (TwoDot, 2016) and has contributed articles for the Tombstone Epitaph and True West Magazine. He currently lives in Montana with his wife and son.

When I was fifteen years old, my father gave me a copy of The Last Gunfighter: John Wesley Hardin by the late Richard C. Marohn. Though I was already fascinated by the history of the American West, my long obsession with El Pasos history began with Dr. Marohns book. I am forever indebted to my father Jeff Dolan for having helped inspire that interest and for the time and photographs that he generously contributed to this book.

I owe a debt of gratitude to John Boessenecker, who encouraged my research and even suggested the title for this book. I could not have asked for a better and more patient mentor and friend. Along the way, John introduced me to a number of other historians and authors, each of whom made important contributions to this effort. They include Donaly Brice, who made numerous trips to the Texas State Archives on my behalf and Kurt House, who generously shared his knowledge and photographs from his personal collection of Old West artifacts. I am also eternally grateful for the help and advice of historians Bob Alexander, Chuck Parsons, Jerry Lobdill, Jan Devereaux, Dylan Maver and Fred Egloff, as well as Bob Boze Bell and the staff of True West Magazine, and Christina Stopka of the Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum in Waco. Other individuals who made important contributions to this book include Ryan T. Hurst, Paul Goodwin, researcher Malissa Arras, Chris Morcom, Mike Testin, Harry Kirk, Steffen Schlachtenhaufen, Michelle Carreon, Erik Wright, Mark Boardman, Claudia Rivers, head of the Special Collections Department at the University of Texas at El Paso Library and her colleagues Abbie Weiser and Anne Allis, as well as Danny Gonzales and Claudia Ramirez of the Border Heritage Center at the El Paso Public Library. I also wish to thank a number of colleagues, friends and mentors who over the years offered no small amount of moral support. They include Jack Bartlett, Peter Sherayko, Bobby Banks, Tim Evans, Phil Spangenberger, Al Frisch, Louis Tarantino, Doug Cohen, Quay Terry, Chris Richardson, Marc Pierce, Bridger Pierce, Troy Batzler, Erin Kaiser and Fritz Statler.

This book was also made possible thanks in large part to the generous assistance of a number of institutions throughout the United States, including the National Archives at Fort Worth, Texas, and Denver, Colorado, The Texas State Library and Archives Commission at Austin, The New Mexico State University Library Archives & Special Collections in Las Cruces, The Office of the District Clerk for the County of El Paso, Texas, The Doa Ana County Clerks Office in Las Cruces, New Mexico, The Nita Stewart Haley Memorial Library in Midland, Texas, The University of Oklahoma Library, The Princeton University Library, The Houghton Library at Harvard University, The DeGolyer Library at Southern Methodist University, The Allen County Public Library in Fort Wayne, Indiana, The Special Collections Library at the University of Texas at San Antonio, The State Archives of New Mexico, History San Jose and The Indiana Historical Society. The Tarrant County District Clerks Office in Fort Worth, TX.

To my agent Claire Gerus, I extend my heartfelt gratitude for having believed in this project and having offered so much meaningful guidance and to Erin Turner at TwoDot Books for having once again allowed me the opportunity to share the stories of the American West. Finally, I wish to express my most sincere love and affection for my wife Suzanne and our son Jack, for their patience, affection and support.

In view of the shooting and general devil-raising going on at El Paso the name should be changed to Hell Paso.

THE ARIZONA SENTINEL

OCTOBER 27, 1877

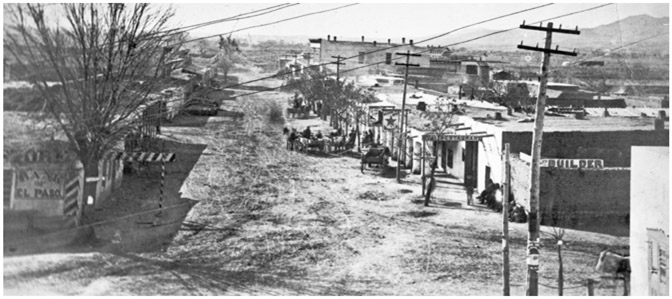

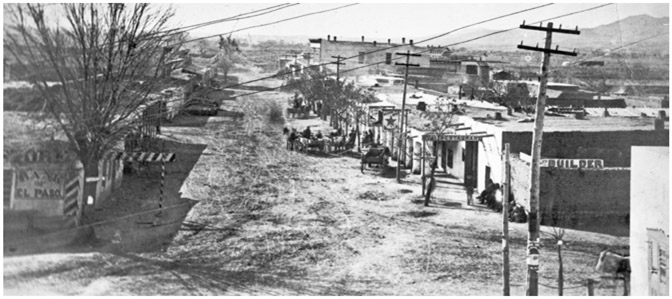

EL PASO MAY NOT HAVE BEEN MUCH TO LOOK AT WHEN DALLAS Stoudenmire first set his gaze upon the border town in the early months of 1881. Indeed, the tall, mustachioed lawman who was, when sober, a dead shot with a .44 caliber Smith and Wesson, might have agreed with another visitor that spring who remarked, Imagine the main street of San Angelo with the houses all flat-roofed, and about a thousand drunken men, railroad hands, gamblers and adventurers, all swaggering, fighting and yelling though the streets, and you have a pretty correct idea of El Paso as it is. The year before, El Paso had counted a population of just 736, a number that included the US soldiers stationed at Fort Bliss. Most of the town was made of sun-baked adobe and confined to a few dirt streets. A jail, which Mayor Solomon Schutz remembered as nothing more than an earthen lean-to, was usually full, although few of the men who should have been put there ever saw the inside of it. They were lawless men who ran things in their own way.

However, the Southern Pacific, the first of five major railways to converge on El Paso, was only weeks away from connecting this remote corner of West Texas to the Pacific coast, and newcomers were pouring in. Real estate in El Paso is rapidly enhancing in value in anticipation of that ancient city becoming a railroad center, one newspaper proclaimed, and people are flocking there from all quarters to get the bulge on the future great city. By late March, the Southern Pacifics construction crews, including some 1,200 Chinese tracklayers, were only 14 miles away and the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe was closing in at a rate of a mile and a half a day. In coming years, the Galveston, Harrisburg and San Antonio, the Texas and Pacific and the Mexican Central would all intersect at El Paso, turning it into a crossroads of commerce and transportation.

El Paso, Texas as it appeared in the early 1880s. COURTESY OF SOUTH EL PASO ST, EL PASO, TEXAS, GENERAL PHOTOGRAPHS COLLECTION, MS 362, UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT SAN ANTONIO SPECIAL COLLECTIONS

In early April, the El Paso Times reported that during the previous six weeks, the population had steadily grown from 963 to 1,500. And it would only continue to explode, reaching more than 10,000 in less than a decade. Situated as it was, many hundreds of miles from any other town, it was a foregone conclusion that El Paso had the making of a great city and was a fine field for investment, Texas Ranger James B. Gillett recalled. Bankers, merchants, capitalists, real estate dealers, cattlemen, miners, railroad men, gamblers, saloon keepers and sporting people of both sexes flocked to the town.

It was during this period of fast-paced development that Stoudenmire appeared in El Paso. Born in Macon County, Alabama, in 1845, the tall, auburn-haired fighting man was both a veteran of the Confederate Army and the Texas Rangers. Over the years, hed come out on the surviving end of a number of shootouts, establishing a reputation as a gunfighter that was enough to gain the attention of the city fathers in El Paso.

Most recently, Stoudenmire had been serving as a peace officer in New Mexico Territory and may have been induced to relocate to the border town by his sister Virginia and her husband Stanley M. Doc Cummings. Mr. and Mrs. Cummings had moved to the city a few months earlier where they opened a restaurant. By some accounts Stoudenmire was sent for by Judge Joseph Magoffin, as a solution to the towns pressing law enforcement needs. Solomon Schutz also later took credit for his coming to El Paso. He had been recommended to me as a brave man and no one knew how badly brave men were needed in these days better than I did, he recalled in 1915. I hired him as town marshal, although the town was collecting no taxes in these days and I had to turn over the fines from the recorders court, where I presided in addition to my duties as mayor.