M. K. Gandhi - An Autobiography

Here you can read online M. K. Gandhi - An Autobiography full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: The Floating Press, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

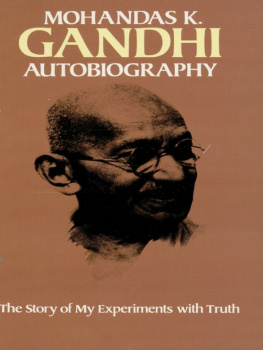

- Book:An Autobiography

- Author:

- Publisher:The Floating Press

- Genre:

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

An Autobiography: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "An Autobiography" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

In this autobiography, also titled The Story of My Experiments with Truth, Mohandas K. Gandhi recounts his life from childhood up until 1921, noting that my life from this point onward has been so public that there is hardly anything about it that people do not know. HarperCollins chose this work as one of the 100 Most Important Spiritual Books of the 20th Century. The pursuit of truth was a guiding principle for Gandhi. He states that it is not my purpose to attempt a real autobiography. I simply want to tell the story of my numerous experiments with truth, and as my life consists of nothing but those experiments, it is true that the story will take the shape of an autobiography. He also notes that this will of course include experiments with non-violence, celibacy and other principles of conduct believed to be distinct from truth.

M. K. Gandhi: author's other books

Who wrote An Autobiography? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

An Autobiography — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "An Autobiography" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Translated by

An Autobiography

The Story of My Experiments With Truth

From a 1940 edition

ISBN 978-1-775414-05-6

2009 The Floating Press

While every effort has been used to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information contained in The Floating Press edition of this book, The Floating Press does not assume liability or responsibility for any errors or omissions in this book. The Floating Press does not accept responsibility for loss suffered as a result of reliance upon the accuracy or currency of information contained in this book. Do not use while operating a motor vehicle or heavy equipment. Many suitcases look alike.

Visit www.thefloatingpress.com

The first edition of Gandhiji's Autobiography was published in two volumes, Vol. I in 1927 and Vol. II in 1929. The original in Gujarati which was priced at Re. 1/- has run through five editions, nearly 50,000 copies having been sold. The price of the English translation (only issued in library edition) was prohibitive for the Indian reader, and a cheap edition has long been needed.

It is now being issued in one volume. The translation, as it appeared serially in Young India, had, it may be noted, the benefit of Gandhiji's revision. It has now undergone careful revision, and from the point of view of language, it has had the benefit of careful revision by a revered friend, who, among many other things, has the reputation of being an eminent English scholar. Before undertaking the task, he made it a condition that his name should on no account be given out. I accept the condition. It is needless to say it heightens my sense of gratitude to him.

Chapters XXIX-XLIII of Part V were translated by my friend and colleague Pyarelal during my absence in Bardoli at the time of the Bardoli Agrarian Inquiry by the Broomfield Committee in 1928-29.

Mahadev Desai, 1940.

Four or five years ago, at the instance of some of my nearest co-workers, I agreed to write my autobiography. I made the start, but scarcely had I turned over the first sheet when riots broke out in Bombay and the work remained at a standstill. Then followed a series of events which culminated in my imprisonment at Yeravda. Sjt. Jeramdas, who was one of my fellow-prisoners there, asked me to put everything else on one side and finish writing the autobiography. I replied that I had already framed a programme of study for myself, and that I could not think of doing anything else until this course was complete. I should indeed have finished the autobiography had I gone through my full term of imprisonment at Yeravda, for there was still a year left to complete the task, when I was discharged. Swami Anand has now repeated the proposal, and as I have finished the history of Satyagraha in South Africa, I am tempted to undertake the autobiography for Navajivan. The Swami wanted me to write it separately for publication as a book. But I have no spare time. I could only write a chapter week by week. Something has to be written for Navajivan every week. Why should it not be the autobiography? The Swami agreed to the proposal, and here am I hard at work.

But a God-fearing friend had his doubts, which he shared with me on my day of silence. 'What has set you on this adventure? he asked. 'Writing an autobiography is a practice peculiar to the west. I know of nobody in the East having written one, except amongst those who have come under Western influence. And what will you write? Supposing you reject tomorrow the things you hold as principles today, or supposing you revise in the future your plans of today, is it not likely that the men who shape their conduct on the authority of your word, spoken or written, may be misled; Don't you think it would be better not to write anything like an autobiography, at any rate just yet?'

This argument had some effect on me. But it is not my purpose to attempt a real autobiography. I simply want to tell the story of my numerous experiments with truth, and as my life consists of nothing but those experiments, it is true that the story will take the shape of an autobiography. But I shall not mind, if every page of it speaks only of my experiments. I believe, or at any rate flatter myself with the belief, that a connected account of all these experiments will not be without benefit to the reader. My experiments in the political field are now known, not only in India, but to a certain extent to the 'civilized' world. For me, they have not much value; and the title of Mahatma that they have won for me has, therefore, even less. Often the title has deeply pained me; and there is not a moment I can recall when it may be said to have tickled me. But I should certainly like to narrate my experiments in the spiritual field which are known only to myself, and from which I have derived such power as I posses for working in the political field. If the experiments are really spiritual, then there can be no room for self-praise. They can only add to my humility. The more I reflect and look back on the past, the more vividly do I feel my limitations.

What I want to achievewhat I have been striving and pining to achieve these thirty yearsis self-realization, to see God face to face, to attain Moksha. I live and move and have my being in pursuit of this goal. All that I do by way of speaking and writing, and all my ventures in the political field, are directed to this same end. But as I have all along believed that what is possible for one is possible for all, my experiments have not been conducted in the closet, but in the open; and I do not think that this fact detracts from their spiritual value. There are some things which are known only to oneself and one's Maker. These are clearly incommunicable. The experiments I am about to relate are not such. But they are spiritual or rather moral; for the essence of religion is morality.

Only those matters of religion that can be comprehended as much by children as by older people, will be included in this story. If I can narrate them in a dispassionate and humble spirit, many other experimenters will find in them provision for their onward march. Far be it from me to claim any degree of perfection for these experiments. I claim for them nothing more than does a scientist who, though he conducts his experiments with the utmost accuracy, forethought and minuteness, never claims any finality about his conclusions, but keeps an open mind regarding them. I have gone through deep self-introspection, searched myself through and through, and examined and analysed every psychological situation. Yet I am far from claiming any finality or infallibility about my conclusions. One claim I do indeed make and it is this. For me they appear to be absolutely correct, and seem for the time being to be final. For if they were not, I should base no action on them. But at every step I have carried out the process of acceptance or rejection and acted accordingly. And so long as my acts satisfy my reason and my heart, I must firmly adhere to my original conclusions.

If I had only to discuss academic principles. I should clearly not attempt an autobiography. But my purpose being to give an account of various practical applications of these principles, I have given the chapters I propose to write the title of The Story of My Experiments with Truth. These will of course include experiments with non-violence, celibacy and other principles of conduct believed to be distinct from truth. But for me, truth is the sovereign principle, which includes numerous other principles. This truth is not only truthfulness in word, but truthfulness in thought also, and not only the relative truth of our conception, but the Absolute Truth, the Eternal Principle, that is God. There are innumerable definitions of God, because His manifestations are innumerable. They overwhelm me with wonder and awe and for a moment stun me. But I worship God as Truth only. I have not yet found Him, but I am seeking after Him. I am prepared to sacrifice the things dearest to me in pursuit of this quest. Even if the sacrifice demanded be my very life, I hope I may be prepared to give it. But as long as I have not realized this Absolute Truth, so long must I hold by the relative truth as I have conceived it. That relative truth must, meanwhile, be my beacon, my shield and buckler. Though this path is strait and narrow and sharp as the razor's edge, for me it has been the quickest and easiest. Even my Himalayan blunders have seemed trifling to me because I have kept strictly to this path. For the path has saved me from coming to grief, and I have gone forward according to my light. Often in my progress I have had faint glimpses of the Absolute Truth, God, and daily the conviction is growing upon me that He alone is real and all else is unreal. Let those, who wish, realize how the conviction has grown upon me; let them share my experiments and share also my conviction if they can. The further conviction has been growing upon me that whatever is possible for me is possible even for a child, and I have sound reasons for saying so. The instruments for the quest of truth are as simple as they are difficult. They may appear quite impossible to an arrogant person, and quite impossible to an innocent child. The seeker after truth should be humbler than the dust. The world crushes the dust under its feet, but the seeker after truth should so humble himself that even the dust could crush him. Only then, and not till then, will he have a glimpse of truth. The dialogue between Vasishtha and Vishvamitra makes this abundantly clear. Christianity and Islam also amply bear it out.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «An Autobiography»

Look at similar books to An Autobiography. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book An Autobiography and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.