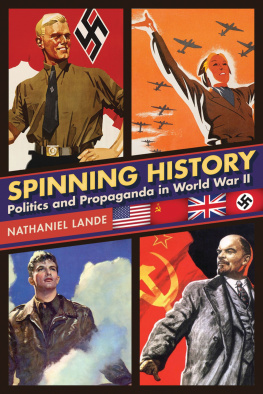

Copyright 2017 by Nathaniel Lande

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Cover design by Rain Saukas

Print ISBN: 978-1-5107-1586-8

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-5107-1587-5

Printed in the United States of America

Contents

Prologue

I f you lived through the 1930s and 1940s and had an interest in the world around you, you may have been aware that political, military, and media leaders used elements of drama and social psychology in the course of World War II. Many still remembered the devastating toll taken by World War I, and governments sought the most effective means of shaping emotions and opinions in this new conflict. Leaders orchestrated and shaped what was an ongoing, evolving history, creating a theatrical framework on both the home front and the front lines by applying elements of drama and new technologies that formed a consensual reality, a reality that fueled a media and entertainment industry that in turnsometimes subtly, sometimes loudlymanipulated and maintained the illusions within and surrounding the war. All sides employed a variety of theatrical devices, each determined to ensure a hit. As in the theater, they competed with one another to make an impression, to secure and hold the audiences interest, to arouse desire, and to provoke a response.

From the National Socialist blueprintthe Hitler script that was Mein Kampf and the elaborate, extravagantly staged Nazi performances at the Nuremberg ralliesto stirring British oratory and radio propaganda, to Roosevelts outmaneuvering of the isolationists on the home front, dramaturgy played a vital role in an event of global consequence.

In their influential work on symbolic interaction, Michael Overington and Iain Mangham document that the parallels between theater and warfare are unmistakable and of vital importance, so that under the direction of political leaders, the rigorous application of theatrical devices created a war-entertainment machine in America and Europe that took on a life of its own.

The broader notion that life and theater resemble one another is by no means just a twentieth- or twenty-first century one; it can be traced back to the dramatic unities of Aristotle and Shakespeare. But in WWII, this dramatic perspective took a new form, and leaders elevated spin to achieve their ends. Media was integrated with politics, spinning a tapestry the world had not yet seen.

In terms of history, drama was used to service this spin, to build a workers or citizens army, to obtain arms, to inspire fighting courage, for land and ideals, for a new society; for a Motherland forged in the Great Patriotic War; a Fatherland built on a utopian platform of world domination.

The freedoms built into Americas arsenal for democracy, the spirit of Avalon carried by the Commonwealth, the collective reforms in the USSR, the National Socialist German Workers Party, were led by master dramatists.

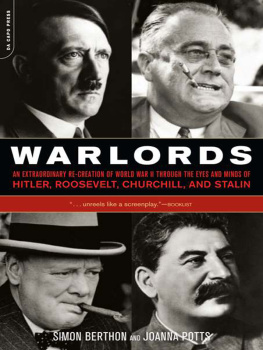

Winston Churchill, Franklin Roosevelt, Adolf Hitler, and Joseph Stalin functioned, as it were, as theatrical entrepreneurs, writer-directors who wrote, enacted, and implemented their own script. Hitlers grand drama for his Third Reich began in the early 1930s. His intuitive understanding of staging and theatrics helped capture an entire nation. For the British, a meticulously realized theatrical structure was used to convince a country, alone against Hitler, of the need and, crucially, of their ability to fight and win an ultimate struggle. In the United States, where both cultural tradition and political pressure were urging Americans to remain firmly backstage, the act of engagement was a high priority for those who needed, by chance or circumstance, to be on the marquee.

Stalins rise was more brutal and less dramatic. He had to apply propaganda to establish his image in the eyes of the public. He had cities named after him; history books were rewritten presenting him as a leader playing a prominent role in the revolution of the Soviet Union and building him to the status of a mythological legend. Controlling media, he had his name included in the Soviet national anthem. Propaganda could build his revolution, but only if the masses rallied behind one another, transforming the message produced by his media machine into reality.

Erwin Goffman, a pioneer of impression management, argued that war, viewed in terms of a theatrical production, demonstrates that reality is or at least can be a reflection of dramatic intrusion. In other words, during wartime, life imitates art in dramatic ways. On all sides at all times during the war, strenuous efforts were made to provoke an emotional response and reaction from the audience. It was a time of costume and conflict, set and soliloquy, music and march, all this underscoring that war, while horribly real, could also be seen as a vast, epic drama, one created to enable populations to accept and cope with a terrifying reality.

As in a wartime film about adventurous aviators or a heroic king on the fields of Agincourt, a theatrical framework allowed political and military leaders to be supported by the entertainment and communications media, to structure the events of the war within accepted and understood dramatic conventions. Each sought to harness their own and the collective national energy to uplift and sustain the morale of their peopleand also to chasten, even silence, critics.

In this war, had you been a general, part of your training would have been to learn to master both tactical skills and, more importantly, strategic ones, to manipulate and guide the behavior of your cast members, soldiers and civilians, in a manner that undermined or rewrote the enemys script, that enacted their own and used it to advance their cause.

If you had been a foot soldier on the front lines, you would have performed in uniform and played a highly risky but decisive role in a drama that demanded an emotional response from its audience back home.

If you were trapped with the British Expeditionary Force on the Western Front in France, you may have been dramatically rescued by the Royal Daffodil or the Bluebird of Chelsea , part of a courageous armada of small fishing craft, steamers, and ferries that took you back to England during the evacuation of Dunkirk and been one of the men who made it back home. You would have participated in what is often celebrated by the Brits, and called the Miracle of Dunkirk, with incalculable misfortune for the German forces.