To that old-time hockey!

INTRODUCTION

OFTEN OVERLOOKED AMONG the beautiful end-to-end rushes, pretty passes, explosive slap shots, and glorious glove saves are the hockey enforcers who ensure the most talented players are allowed to shine.

Before the enforcer came into being, players of all sizes and skills were on their own and were expected to take care of themselves. All-Star defenceman Eddie Shore, who routinely excited crowds with his rushes and scoring prowess generations before Bobby Orr would do the same, accumulated 978 stitches before retiring from the game. And before him, many a player was cut down with fouls that left a gash on his head and a pool of blood in his wake. Those who refused to get back up to fight another day were quickly drummed out of the sport.

The game of those early days makes todays hockey seem tame. The players were ruthless and brutal, many seemingly on a mission to stop the opposition by any means necessary. And often those means included a heavy stick, which they used with little or no restraint, chopping one another down with crushing blows that would earn them lifetime suspensionsand perhaps even lengthy prison termstoday.

Then along came the enforcer, who would instill fear into opponents who previously had no qualms about belting smaller, more talented players into submission. The first one to come along to protect people was [John] Ferguson, said Hall of Fame defenceman Pierre Pilote. There were other fighters in the league, but all of a sudden we noticed Ferguson was going to be protecting the guys.

Thanks to the muscle Ferguson provided for his Canadiens teammates, hockeys most gifted would be given a better chance to demonstrate their talents without fearing for their health or being forced to respond in kind to the wild men who would otherwise have squashed them, dragging them to the penalty box in an unequal exchange of talent.

By the expansion era, the game had regressed to an earlier period of brutality as the new franchises, thin on talent, promoted the toughest and most desperate to escape the bush leagues in order to intimidate their way to victories. Other teams responded and, eventually, balance was again restored as every winning club had deterrents on their benches. No longer could any team rule by sheer force alone.

Enforcersprotectors whod let the opposition know that transgressions against their stars would not be toleratedremained prominent in the 1980s. With heavies like Dave Semenko looking out for him, a lanky superstar by the name of Wayne Gretzky would rewrite the record books and last 20 years in what was once the most violent professional sport on Earth. Gretzky knocked Gordie Howe off in the record books, but it is unlikely he could ever have knocked him off on the ice, though they did faceoff against each other at the beginning of the Great Ones career and at the end of Howes. After all, the Gordie Howe Hat Tricka goal, an assist, and a fightis still referenced today.

Howe is just one of numerous stars in the leagues history to have demonstrated a flair for fisticuffs to go along with his scoring prowess.

Besides owning the Norris Trophy, Bobby Orr was a tough guy who had no problem throwing down. Orr would be tested in his rookie season as veterans looked to see if the new golden boy would back down. He wouldnt, mixing it up with Montreals Terry Harper and New Yorks Reg Fleming. Orrs fights wouldnt be confined to his first pro year, and hed prove himself handy, even holding his own against the likes of the Rangers Orland Kurtenbach.

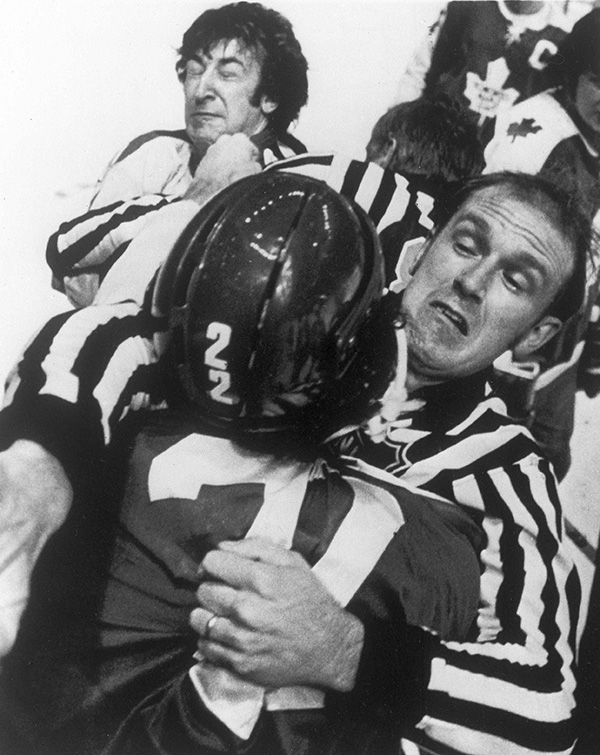

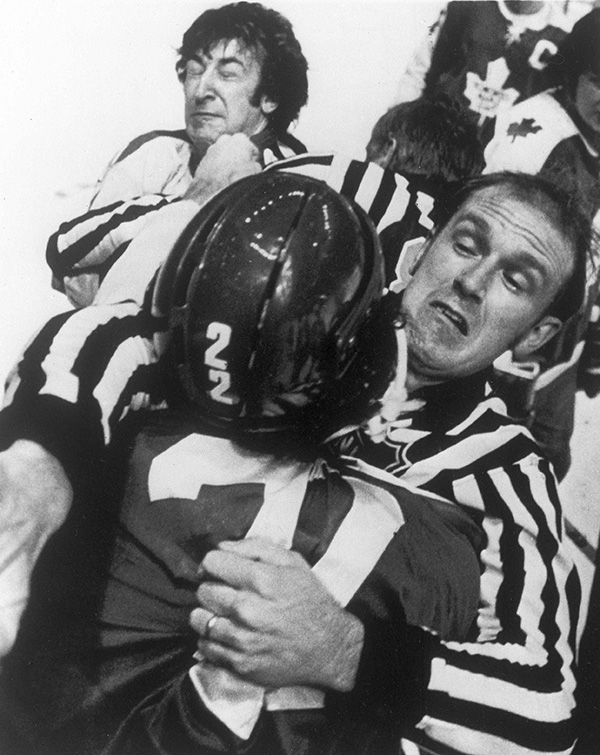

Dave Tiger Williams of the Toronto Maple Leafs lands a left on the jaw of Guy Lapointe of the Montreal Canadiens while being held by the linesman during a game in December 1975. (AP Photo/DMB)

Typically hed raise his hands in retribution, flashing his temper if hed been wronged on the ice. He went wild after Torontos Brian Conacher accidentally clipped him on the nose, steaming through teammates to get at Conacher and then mauling him. After Pat Quinn of the Leafs knocked him out with an elbow, Orr gave him his receipt, dropping the gloves and pounding away on Quinn after he fell to the ice. Opponents took notice of such vengeful attacks. Also not lost on them would be the severe retribution the Big Bad Bruins or Lunch Pail Gang would inflict on anyone taking liberties with Orr.

Besides being an All-Star defenceman for the New York Rangers, Brad Park showed up for any challenges thrown his way and engaged in numerous fights. But when he went to Boston, Don Cherry told him to turn the other cheek since his value was greater on the ice than in the penalty box: Deep down, I loved it when Brad fought, but I had my designated fighters, and he wasnt one of them, Cherry wrote in Grapes.

Opponents recognized Parks value to the Bruins and would try to goad him into fights. Cherry had had enough when Detroits Dennis Polonich drove Park to go after him, which resulted in Park getting thrown out of the game. Afterwards, Cherry told reporters Park was forbidden to fight and if he did, hed get fined. I told the entire league, in effect, that Park was no longer permitted to fight so he, therefore, no longer felt obliged to display his toughness and we were all the better for it, Cherry wrote.

Another 70s All-Star, Larry Robinson, was feared for his size and big open-ice hits. And although he didnt get in many fights, his pugilistic acumen deterred most from bothering this particular member of Montreals Big Three. At 6-foot-4, Robinson towered over his peers and was one dandy fighter, typically mopping the ice with anyone he faced, even a heavyweight specialist like Dave Hammer Schultz.

Power forwards also hurt other teams, with their scoring touch and physical intimidation.

Wendel Clark of the Leafs came into the NHL with all guns firing, hitting and fighting everything that moved, no matter how big. He had no qualms about taking on enforcers like Bob Probert, Behn Wilson, and Marty McSorley.

Talk about giving 100% in a fight, thats what he did. Its not always the biggest dog in the fight, said Todd Ewen. Theres lots of guys who can throw a punch but not a lot of guys who can really throw a punch. A lot of people think that you throw a punch with your shoulders and arms, and Wendel threw with his legs. It came from his toes all the way through his hands and when he threw he had bad intentionshe was awesome and thats why he did so well.

Wendel Clark had a huge impact on the game. He could play any way you wanted to play, added Dave Manson. He wasnt the biggest guy in stature, but he played a big mans game. Plus he could score, plus he could hit, plus he could fight, plus, plus. Wendel was the epitome of a power forward back in the day.

But given that Clark was by far the best Leaf on the ice, he sometimes needed reining in. When the Red Wings assigned Joe Kocur to shadow Clark in the 1987 Norris Division Final, John Brophy forbade Clark from duking it out with his cousin. Even a legendary minor-league roughneck like Brophy could see no upside in Toronto losing its best man in exchange for a role-player like Kocur.

Clarks style also forced him to cut back on his fighting. His first two years of vigorous play took their toll, giving him back problems that nearly caused him to retire and forced him to miss most of three straight seasons. When he returned as a regular, his fight card wasnt nearly as full as it had been during his first two years.

![Oliver - Around the World with One Direction - The True Stories as told by the Fans]](/uploads/posts/book/100930/thumbs/oliver-around-the-world-with-one-direction-the.jpg)