ABOUT THE AUTHOR

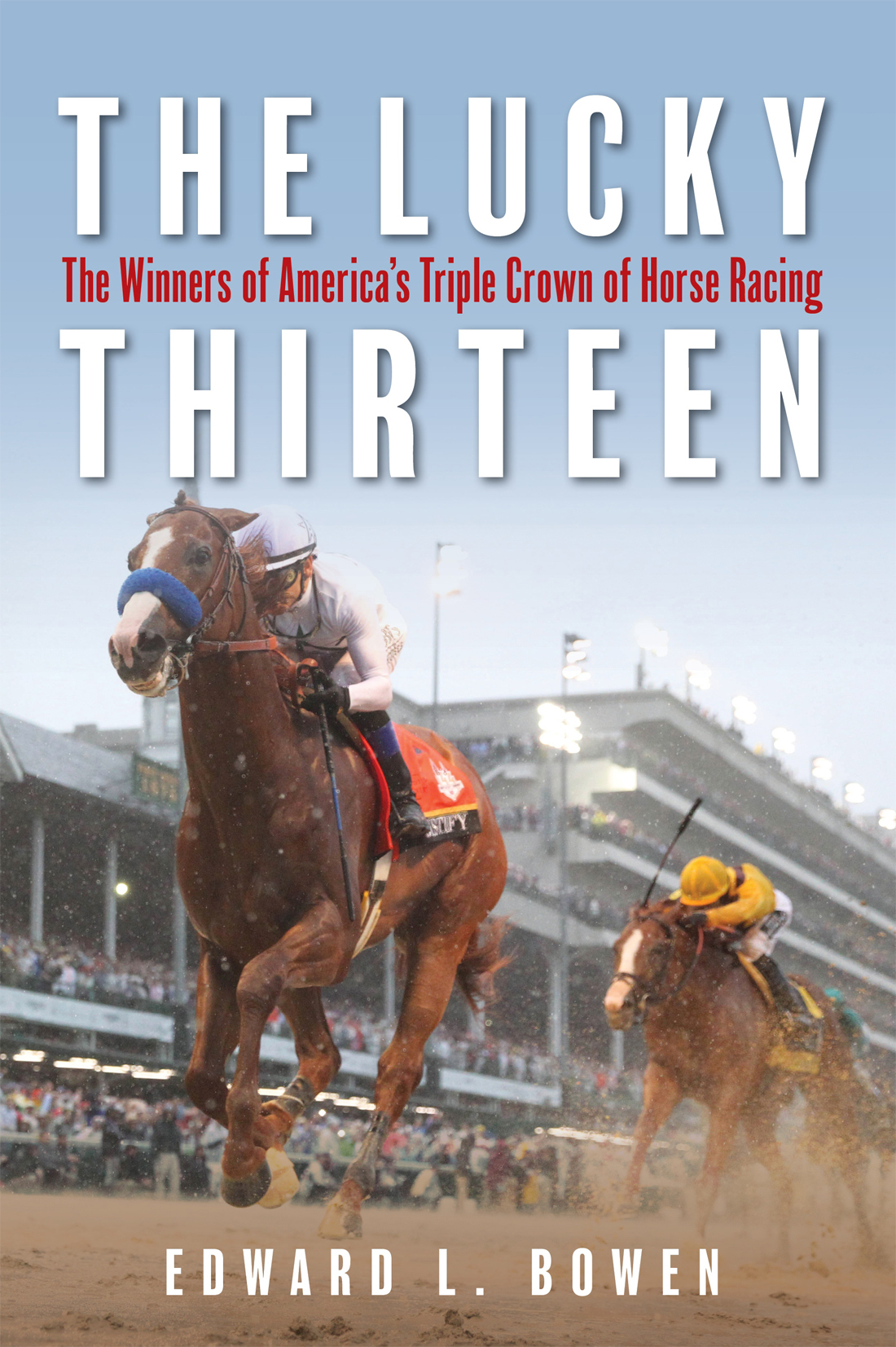

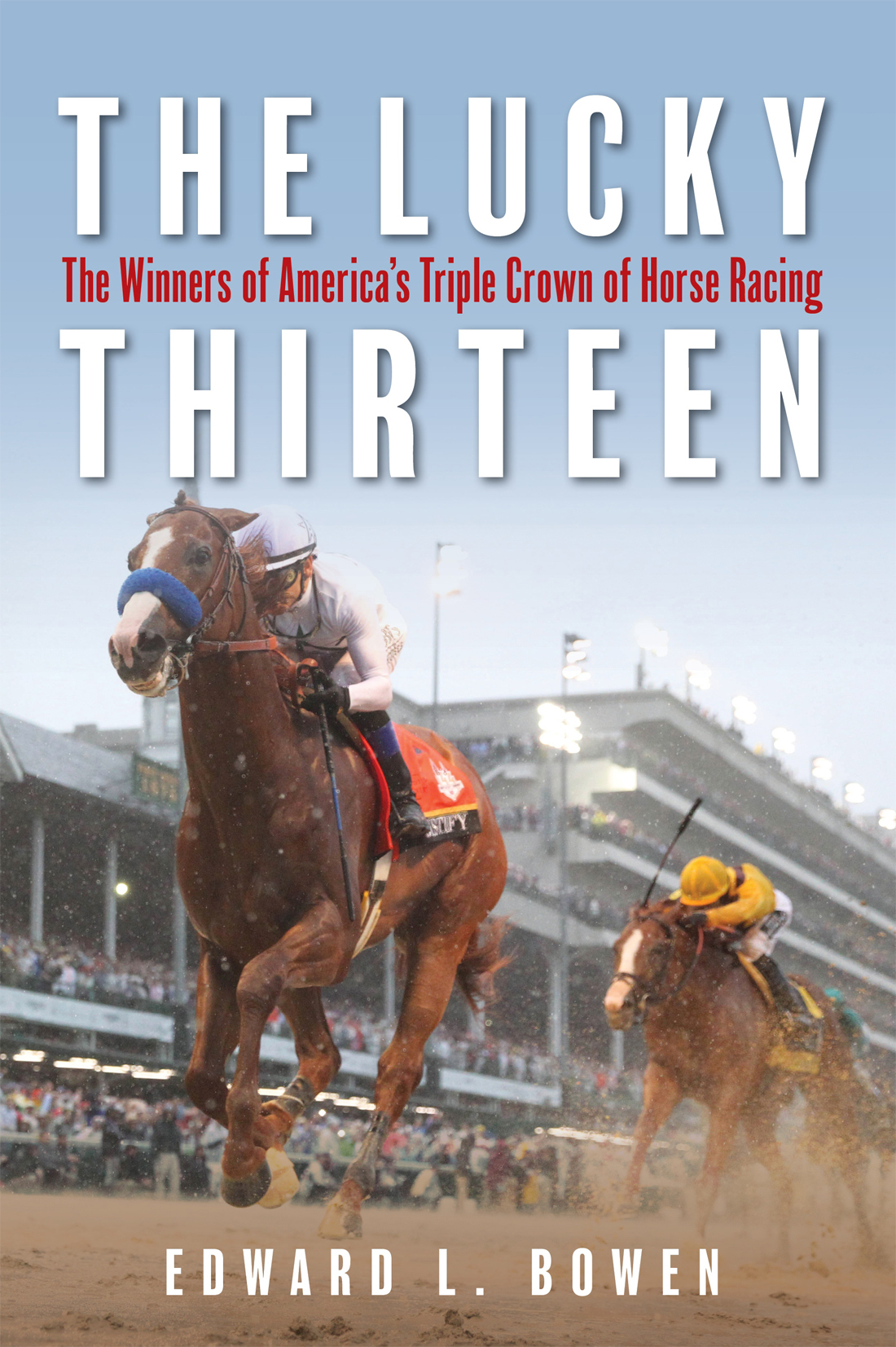

The Lucky Thirteen: The Winners of Americas Triple Crown of Horse Racing is Edward L. Bowens twenty-first book on Thoroughbred racing history. Bowen was a staff member of the weekly trade publication The Blood-Horse for some thirty years, including seventeen as managing editor and five as editor in chief. He was also editor of The Canadian Horse for two years. Bowen served as president of the Grayson-Jockey Club Research Foundation from 1994 through 2018. Grayson traditionally is the leading source of private funding to support veterinary research fostering the health and soundness of horses of all breeds and activities. Bowen has received various honors within the world of Thoroughbred and sports journalism and authorship, including an Eclipse Award for magazine writing, the Charles Engelhard Award from the Kentucky Thoroughbred Association, the Old Hilltop Award from Pimlico Race Course, the Walter Haight Award from the National Turf Writers Association, and the gold medal designation in Foreword s sports category.

An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Blvd., Ste. 200

Lanham, MD 20706

www.rowman.com

Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK

Copyright 2019 by Edward L. Bowen

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

ISBN 978-1-4930-3967-8 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-1-4930-3968-5 (e-book)

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/ NISO Z39.48- 1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/ NISO Z39.48- 1992.

Printed in the United States of America

INTRODUCTION

Organized Thoroughbred racing began in England, and so too did the Triple Crown. Horse racing in England started in the medieval era, when owners hired professional riders to showcase their horses speed to potential buyers. The first known racing purse was offered during the reign of King Richard I (1189 1199). The practice was carried forward by his royal successors, notably Henry VIII, James I, Charles I, and Charles II, during whose reign horse racing became a spectator sport.

Over centuries, a framework was established as to which horses could be included in organized races. The collective stock being developed from a variety of English and Irish equine and exotic imports was designated the Thoroughbred.

In 1779, the English Oaks was run for the first time, and the next spring saw the first running of the English Derby. Both took place at Epsom Downs, which remains their home today. By the middle of the nineteenth century, one Admiral Rous had segued from a distinguished career in the Royal Navy and was a stalwart in the organizational aspects of the Turf (a collective term referring to the breeding, raising, racing, and general management of the Thoroughbred). Noting the patterns of races and their relative importance, Admiral Rous created a designation he called classics. The classics of English racing, he decreed, would be the five races of the following names: the One Thousand Guineas, the Two Thousand Guineas, the Derby, the Oaks, and the St. Leger.

These were well-established races, each intended to be contested only by three-year-olds; hence, the development of the phrase classic generation. Like other races, they had prescribed conditions for their running. The One Thousand Guineas and the Oaks were for three-year-old females (fillies), while the Two Thousand Guineas, the Derby, and the St. Leger were for three-year-olds of both genders. The distance, too, became set: 1 mile each for the Guineas races, 1 1/2 miles for the Derby and the Oaks, and 1 3/4 miles for the St. Leger. These races survive today, and have remained in placeto wit, the Guineas at Newmarket (race course), the Derby and the Oaks at Epsom Downs, and the St. Leger at Doncaster.

Over the years, these became the most glamorous races in England, and the three involving the colts came to be known as the Triple Crown. English historians regard this as a gradually popularized term, and the historian John Randall noted that the expression had entered common usage by the time of Ormonde (1886), having evolved naturally without ever being endorsed by the Jockey Club or any other official body.

Between 1853 and 1866, the Guineas, the Derby, and the St. Leger were won by West Australian, Gladiateur, and Lord Lyon. It was twenty years later that Ormonde swept through the three. The designation of Triple Crown winner was assigned to that earlier threesome in retrospect. After Ormonde, the English Triple Crown was won by Common (1891), Isinglass (1893), Galtee More (1897), Flying Fox (1898), Diamond Jubilee (1900), Rock Sand (1903), Pommern (1915), Gay Crusader (1917), Gainsborough (1918), Bahram (1935), and Nijinsky II (1970). (During both world wars, the Derby was run at Newmarket instead of Epsom.)

In the United States, the horse-racing establishment attempted to replicate the English Triple Crown. Colonel Meriwether Lewis Clark Jr. set out to duplicate the series at his own track, Churchill Downs in Kentucky, but of the three races he tried to cast in that light, only the Kentucky Derby became recognized as a classic event.

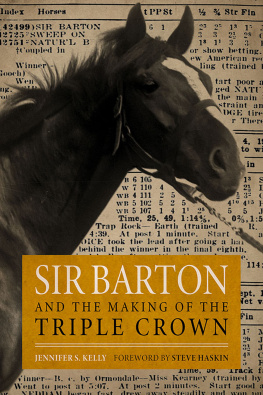

In New York, racing leaders focused on the Belmont Stakes, which was run on a date close to the Epsom Derby and over a similar distance. The thought was to precede the Belmont with the 1-mile Withers Stakes and then round off a Triple Crown late in the summer with the Realization Stakes, at a distance similar to that of Englands St. Legers. The great Man o War won all three of those races in 1920, but, ironically, that was only a year after Sir Barton had won the series of races which would become cemented in the American Turf as its own Triple Crown. Those races are the Derby, Marylands Preakness, which had increased in purse and prestige to muscle into the scenario, and the Belmont.

The Belmont thus is the climax in distance and on the calendar rather than an Epsom counterpart. The American Triple benefited rather than suffered from its illogical aspects. Instead of a progression of lengthening distances, its pattern is 1 1/4 miles, slightly shorter at 1 3/16 miles, and then up to 1 1/2 miles. As for placement on the calendar, it is all crammed into five weeks, although its rise to high acceptance took place with slightly varied schedules.

The short interval from the Kentucky Derby to the completion of the Belmont promotes greater fan and public interest than likely could be maintained over a time frame of from late April into September. The fact that Englands original Triple Crown now is apparently weighed down by what once seemed impeccable logic is justification for leaving the American Triple Crown the way it is. Racing fans were lucky in how it developed and smart enough to let it flourish as is.

The American Triple Crown has been characterized by long and short periods between winners. After three horses swept the races in the 1930s, and four in the 1940s, there was a drought of twenty-five years between Citation (1948) and Secretariat (1973). Then came two more Triple Crowns by the end of the decade in Seattle Slew (1977) and Affirmed (1978). Seven horses between Citation and Secretariat had won the Derby and Preakness before the letdown of not winning the Belmont. Between Affirmed and American Pharoah, a longer drought of thirty-seven years taunted the Turf, and within those years no fewer than thirteen horses won the first twobut not the third.

Next page

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/ NISO Z39.48- 1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/ NISO Z39.48- 1992.