Copyright 1992 by Zhai Zhenhua

All rights reserved

Published in the United States of America by

Soho Press, Inc

853 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

Published in Canada by

Lester Publishing Limited

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Zhai, Zhenhua, 1951

Red flower of China / Zhai Zhenhua

p cm

ISBN 0-939149-83-4

1 Zhai, Zhenhua, 1951- 2 Hung wei pingBiography

3 ChinaHistoryCultural Revolution, 19661969 I Title

DS778 Z47A3 1993

951 056dc20

[B] 92-44047

CIP

Manufactured in the United States

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3

To Danny, with love

To China, with hope

CONTENTS

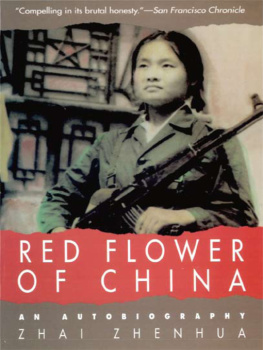

I was born in China in 1951, a little more than a year after the Communist Party took power on October 1, 1949. My generation was called the Socialist New Generation. Older people used to tell us how lucky we were, never having had to taste the bitterness of the dark, old society and the war. You are born on sugared water and brought up on sugared water; when you grow up, you are going to have a much better life than we had, they said. I felt full of hope.

But before we grew up, the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) erupted. My education was interrupted and my entire life was altered. I became a Red Guard, attacked people ruthlessly, and in the end was attacked myself. In 19691 was sent to the countryside to be reeducated by the poor and lower-middle-class peasants. There I did back-breaking labour and ruined my health. It wasnt until 1972 that I managed to get into university to continue my education.

When the Cultural Revolution finally ended my generation had an unofficial new title: The Destroyed Generation. Older people now shook their heads, some with pity and some with spite; they believed that we had learned nothing in life but revolution. In a sense, they were right. But why were we destroyed? How did it all happen?

This book tells my story. From my idealism and patriotism before the Cultural Revolution to my excitement and frustrations as an active participant in it to my disillusionment with Mao Zedong when I was exiled to the countryside, I recount my eventful early life in China. Many people in the West know of the Red Guards. Few, if any, are familiar with their backgrounds and motivations, and what ultimately befell them and their generation. I have written this book so people will know the whole story.

My greatest and deepest thanks are due to my philosopher-husband, Danny. Without him I would never have dared to start this project, and without his persistent urging and support this book would not have survived its many crises He was my reader, critic, and first editor. For the hours and hours he put in, for the painstaking efforts he has made, he truly deserves the dedication.

I am in debt to Professor Robin Skelton, now retired from the Creative Writing Department of the University of Victoria. He read an early draft of the book, assured me of its value, and provided some professional hints about writing that were very helpful in later drafts.

I also owe my agent, Denise Bukowski, and my editor, Nancy Flight. Denises enthusiasm for the book brought about its publication, and Nancys skill in editing and right-to-the-point comments and suggestions brought it to its present state.

Finally, my gratitude is extended to my sister-in-law, Judy G. Daniels, for her encouragement and suggestions, and to all my relatives in China who have given me their support.

I KNOW LITTLE ABOUT MY GRANDPARENTS. THEY LIVED IN the countryside in Shandong Province, which runs along the centre of the east coast of China, and died early, except for my fathers mother, who died in 1974 at age eighty-two. She came to visit our Beijing home twice, once in 1961 and again in 1962. That was all I saw of her.

The first time we met she was sixty-nine. Her teeth were gone, her mouth shrivelled, and her hair silver-grey. She was a small woman, five-foot-one and weighing no more than ninety pounds, with delicate features and fair skin. She wore her hair in a bun at the nape, and her attire was that of a typical countrywoman in the old days: her body was deeply hidden in a loose, dark-coloured Chinese jacket buttoned at the side, and she wore loose, black slacks string-tied at the bottom even on the hottest summer day. Her bound feet were packed in many layers of white fabric and fitted into a special pair of triangular-shaped shoes. In old China womens feet were bound to reduce their length. Before a young girls feet were grown all her toes except the big one were bent under the sole and her insteps were folded. Her feet were then swathed tightly with long cotton bands to keep them in that position. For months she had to endure the pain as she walked. The deformation then became permanent and the pain diminished. A woman with natural, large feet was considered ugly, while a woman with a pair of three-inch golden lotuses was considered beautiful. Although not quite the ideal three inches, Grandmas feet didnt miss it by far.

Everything about Grandma seemed odd, not just her appearance. When I asked what her name was she said: Fan Shi, which means maiden name Fan. I had to think for a while before I understood. In old China all married women were referred to that way Zhang Shi, Li Shi, or whatever Shi. I had only read names like that in novels. We were now in the sixties, some ten years after Liberation. Grandma couldnt be so old-fashioned as to keep using that kind of name. Maybe she has two names, I thought. I asked again: What is your name? Your own name? She repeated Fan Shi. Then, seeing my still-incredulous look, she asked for paper and pencil. I took her to the writing-table where they were. She sat down and, with much ado, drew two barely recognizable characters in extra-large size Fan Shi. It was her only name.

Every morning before getting up Grandma sat on the bed, combed her hair, made the bun at the nape, and then patiently wound the long, long strips of cotton tightly around her feet. The winding was essential to keep her bound feet in shape. Some days the ritual was completed smoothly. Other days it wasnt, and she would untie the binding and begin again and again until it was absolutely comfortable.

In those days Grandmas style of clothing and triangular shoes were available in department stores. When my parents went shopping for her, Grandma would go along to make sure that everything fit. She couldnt keep up but didnt want us to wait for her, so inevitably she trailed way, way behind. I joined them on a couple of these outings and saw how she walked, splay-footed, in tiny steps, hurriedly moving her legs at almost a run. After a few hundred feet, she would become exhausted and have to find somewhere to sit down and rest.

Next page

![Flower - China: [the essential guide to customs & culture]](/uploads/posts/book/200771/thumbs/flower-china-the-essential-guide-to-customs.jpg)