Table of Contents

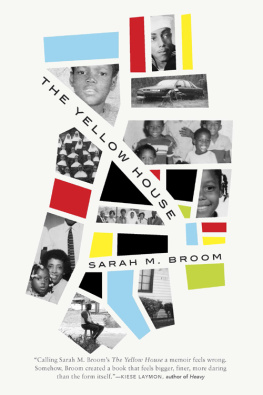

PENGUIN BOOKS

RED HOUSE

Sarah Messers work has been published in The Paris Review, The Kenyon Review, Story, and many other journals. She has received a Mary Roberts Rinehart Award for Emerging Writers, and grants and fellowships from the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, the American Antiquarian Society, and the National Endowment for the Arts. She is the author of a book of poetry, Bandit Letters, and teaches poetry and creative nonfiction at the University of North Carolina-Wilmington.

For my parentswho made everything possible and in memory of Richard Warren Hatch, who gave us the story

Old houses that have sheltered a family for 300 years are forever invisibly inhabited by jealous ghosts, and it is absolutely essential for any dweller therein to get them on his side.

Richard Warren Hatch, 1966

This earthly house must be dissolved, that is the bodyes of gods children, that theire soules now dwell as in a house, an earthly house the body is....

Increase Mather, 1687

Of those so close beside me, which are you?

Theodore Roethke

PART ONE

North side of Red House

HATCH: To keep silence. A hatch before the door. HATCH (nautical) A moveable planking forming a kind of deck in ships. Under Hatches = below deck. Over Hatches = overboard. A square or oblong opening in the deck by which cargo is lowered into the hold. Under the Hatches : Down in position or circumstances; in a state of depression, humiliation, subjection or restraint; down out of sight. HATCH: A wooden bed frame. A hatchet. A knot. To incubate. To brood. HATCH: The action of hatching, incubation; that which is hatched, a brood of young. HATCH: To engrave or draw a series of lines, usually parallel.

Partial definition,Oxford English Dictionary

One

Red House, circa 1900

Before the highway, the oil slick, the outflow pipe; before the blizzard, the sea monster, the Girl Scout camp; before the nudist colony and flower farm; before the tidal wave broke the rivers mouth, salting the cedar forest; before the ironworks, tack factory, and shoe-peg mill; before the landing where skinny-dipping white boys jumped through berry bushes; before hay-field, ferry, oyster bed; before Daniel Websters horses stood buried in their graves; before militiamens talk of separating; before Unitarians and Quakers, the shipyards and mills, the nineteen barns burned in the Indian raideven then the Hatches had already built the Red House.

The surname Hatch most commonly means a half-door, or gate, an entrance to a village or manor house. It describes a person who stands by the gate; a person newly born; a person who waits.

My father could not wait. He had made an appointment with a real-estate agent, but when he found himself on a house call in Marshfield, Massachusetts, he decided to see the Red House himself. It was August 1965, and he was a thirty-three-year-old Harvard Medical School graduate with a crew cut and bow tie, married to my mother for just four months. Done with his residency and his army service, he had begun to specialize in radiologybroken bones, mammograms, GI series. The practice of seeing through people. With all the self-consciousness of a latter-day Gatsby, he would eventually raise a herd of kids patchworked together as New Englandersfour from his first marriage, four with my mother. But for now he was moonlighting for extra cash and driving his sky-blue VW Beetle down dirt roads, into brambles and dead-ends.

Marshfield, then as now, is a coastal community thirty miles south of Boston, 225 miles north of New York City, whose famous residents over the years have included The Great Compromiser Daniel Webster, some Kennedy offspring, and Steve Tyler of Aerosmith. Driving through the north part of town, my father passed seventeenth- and eighteenth-century houses, two ponds where mills had been. The afternoon light lay drowsy, the air motoring with insects. He knew he was getting close to something, and his stomach clenched. He had always loved ancient rooflines and stone walls, half-collapsed barnstemplates of what had come beforeplain churches, fields rolling down to rivers, shipyards. Yet, within this two-mile stretch, modern houses and gas stations had grown up around their remains like flesh over bone. He was following his intuition, as if, eyes closed in a dream, he felt his way with his hands stretched out. The road began a violent S-curve at the edge of a string of ponds. At the blind part of the curve, my father found the road to the house, and turned there to begin the half-mile drive past yet another pond.

He drove by the dilapidated Hatch Mill, over the narrow bridge, then through a canopy of crab-apple trees, over a stream that ran beneath the road. It was the last few weeks of summer, and the timothy was high at the roadside, the milkweed setting off parachute seeds.

Meanwhile, in the adjacent town of Norwell, in the apartment he was renting, my mother was preparing his four children for a bath. They were: Kim, seven; Kerry, five; Kate, four; and Patrick, three. The children were spending the summer away from their mother in California. They had been to Marthas Vineyard, Bensons Wild Animal Farm; they had spent the day riding bicycles on the blacktop driveway.

Lately a raccoon had been banging the lids of the garbage cans below the second-floor bathroom window each night. That raccoon with his black mask, that thief, theyd say. My mother was relieved: animal stories were common ground. She said, Its getting dark; do you think the raccoon is out there? She squeezed Johnsons baby shampoo into one hand, and then turned the water off. The children shrieked, Raccoon! Raccoon! Pale-skinned kids with tan lines: Kim, tall, broad-cheekboned; Kerry and Patrick, a girl-and-boy matched pair with the same androgynous haircut; Kate, a tantrum-throwing tow-head.

My mother, twenty-seven years old and petite, wore her hair long, usually in braids or in a large bun with a thin path of gray twisting through it like a skunk stripe. That day she wore it in a ratty ponytail, having had no time to brush it. Her only cosmetics: an occasional eyebrow-penciling, and lipstick in the evening if she was going out.

It had been almost four years since my mother, a lab technician, had met my father at the cafeteria in Childrens Hospital in Boston. As she stood in line, she saw him leave his dirty plate and tray, linger, exit the cafeteria, and then return to the line. He was wearing his signature bow tie. He approached her and asked her to have lunch with him.

You already ate, she said.

Ill eat again, he replied.

From the beginning, my father had mentioned his divorce and his custody of the children for school vacations and three months every summer. Early in the relationship, my father had brought my mother and the children to Cape Cod, where she had her own room in the rented cabin. Nearly every night, Kim had sanded and short-sheeted the bed, leaving seaweed and crabs under the blankets. Besides these incidents, though, the children gave her little indication that she was unwanted. Summer was over, and the next day they were returning to California. The bathtub was by the window, and when they stood at the edge, the children could look down on the dented lids of the three garbage cans. My father had said that the house call would take only an hour at most. Now it was getting late, and my mother had no idea where he was.