Copyright 2014 Eric S. Morse

Published by Iguana Books

720 Bathurst Street, Suite 303

Toronto, Ontario, Canada

M5V 2R4

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise (except brief passages for purposes of review) without the prior permission of the author or a licence from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For an Access Copyright licence, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

Publisher: Greg Ioannou

Editor: Amanda Plyley

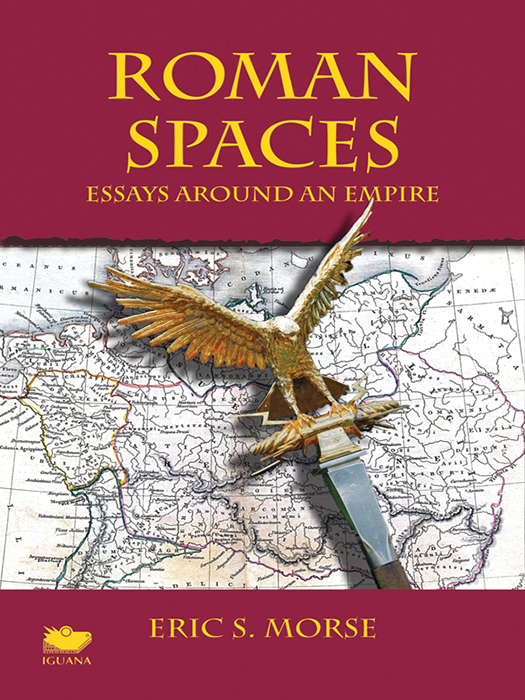

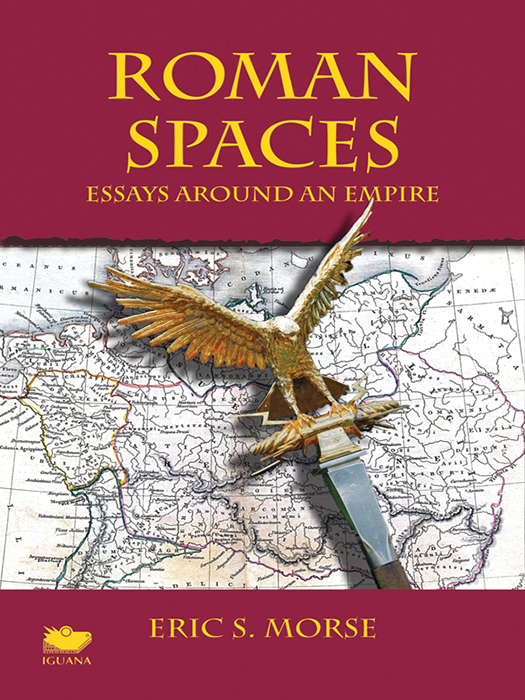

Front cover image: Replica Legionary Eagle standard of re-enactor unit X Gemina, The Ermine Street Guard: 2014.

Front cover map: Germania, published by Harper and Sons, New York, NY: 1849.

Front cover design: Eric S. Morse

Book layout design: Amanda Plyley

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Morse, Eric S., 1949-, author

Roman spaces : essays around an empire / Eric S. Morse.

Includes bibliographical references.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-77180-087-7 (pbk.).--ISBN 978-1-77180-088-4 (bound).-

ISBN 978-1-77180-089-1 (epub).--ISBN 978-1-77180-090-7 (kindle).-

ISBN 978-1-77180-091-4 (pdf)

1. Rome--Civilization. 2. Rome--History--Empire, 30 B.C.-476

A.D.

I. Title.

| DG77.M67 2014 | 937.06 | C2014-907282-1

C2014-907283-X |

This is an original ebook edition of Roman Spaces: Essays Around an Empire.

Dedication

To Val Ross (1950-2008), littratrice, mentor and friend, who steered me gently into writing about issues, including Roman ones; to Mary Janigan and Morton Ritts, who braced my nerve through six years of lectures; to the Members of the Royal Canadian Military Institute in Toronto who have turned out staunchly to the lectures; to the friends and family who have put up with my Romanist obsession for years.

And with especial gratitude to

KATHRYN E LANGLEY HOPE

PATRON LIBERALISSIM OPTIM MAXIM AMIC CARISSIM

Dear friend, long-time patron and generous sponsor of this work.

Foreword

Those who know Eric Morse from his columns in the Ottawa Citizen or from his presentations at the Royal Canadian Military Institute will find in Roman Spaces the traits that make this libellum so engaging and well worth reading. Entertaining and endearingly irreverent on the one hand, pragmatic, probing, and learned on the other, Eric has a way of making his readers reconsider accepted wisdom or grand hypotheses built on questionable foundations. Unlike so many, he keeps his footing on the slender tightrope of reliable evidence. He disclaims any attempt at original scholarship, but here I put it to the reader that his essays serve an even more useful purposeto look at the Roman past from fresh perspectives and, mutatis mutandis, compare the experience of that past with contemporary affairs. Roman Spaces is yet another reminder, in a day and age when the humanities seem to have gone badly astray, that the study of the classics retains its core value as the study of human nature. Character was destiny in the eyes of the ancients; and from Homer, to the Greek tragedians, to the Greek and Roman historians, to Vergil, and on through Plutarch, they sought to explain how human beings with their strengths and weaknesses, within their lights, surmounted or faltered before the constraints, limitations, imperfections, and pressures of this world.

It is odd and unfortunate that modern historians frequently make no place for people in their work, preferring instead to examine events, forces, or trends as though human beings and human agency have no role. Refreshingly, Erics pieces become all the more worth reading for the attention he pays to the human factor and for the common sense he brings to his discussions. Speaking from my perspective as an old Byzantinist, I find the Byzantine world, with its self-fashioned, alluring image of order and stability, priding itself as being the very kingdom of heaven on Earth governed by Gods regent, very much like the Roman world that can easily deceive us into thinking that the image of the Pax romana was the reality. It is Erics approach to ask what in fact was possible, what was feasible, what was real or realistic behind the image. Numbers matter, time matters, geography matters, distances matter, and so does our recognition of the realm of information or choice available to the emperors, commanders, or politicians at a given moment.

Every essay in this book reads like a good conversation, true to the spirit of the Greek and Roman historians who wrote works to be read aloud, argued over, and enjoyed. And so it is a pleasure to extend a Latin invitation to readers: tolle, lege, laetaberis pick up this book and read it, youll be happy that you did.

Dr. Eric McGeer, Toronto

Introduction

Thats the thing about the past, you can find anything you like there.

Dr. Margaret MacMillan, Munk Centre University of Toronto, March 24, 2014

It was just after the 1974 Canadian federal election that Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau, having said during the campaign that he would not bring in wage and price controls, did so. Instantly, Canadian pundits discovered the Roman Emperor Diocletian, who had brought in something that at least looked similar in 301 CE. There were editorials citing Diocletians Edict on Maximum Prices as a sure guarantee that universalist remedies were doomed to failure.

In due course I encountered a book of essays, Aspects of Antiquity, by Dr. M. I. Finley, who explained gently that Diocletian was no ideologue but a simple military man and autocrat, that he was (as he himself says in the Preface to his Edict) upset that inflation was devaluing his soldiers pay, and that when the solution obviously didnt work, he simply walked away from it a year or so later because he had not drunk any intellectual bathwater that would have committed him to sticking with a lost cause. Among other things, he didnt have to face an election campaign.

Trudeaus anti-inflation measures lasted four years, were intended as a temporary measure, were far more limited in scope, and may have helped him to lose the 1979 election. The only really useful takeaways from Diocletian are: (1) what a miracle of organization it was that with fourth-century administrative technology and communications, the Imperial bureaucracy was able to compile so comprehensive and accurate a table of values for just about everything available in the Empire, and (2) how dangerous it is to pull historical comparisons out of a hat.

This book, which is based on a series of lectures given to the Royal Canadian Military Institute between 2008 and 2014 and dedicated to the late Canadian littratrice and commentator Val Ross, attempts something of the reverse. Its key chapters attempt to look at the Romans position in their world through the lens, gingerly applied, of modern geopolitics and in particular of the lessons we are now trying to learn from the past decade, when it has become clear that the global universe of a hundred and ninety-three sovereign players and heaven knows how many others is a far more complex and fragmented power structure than the old bipolar world was, or than we ever imagined.

Next page