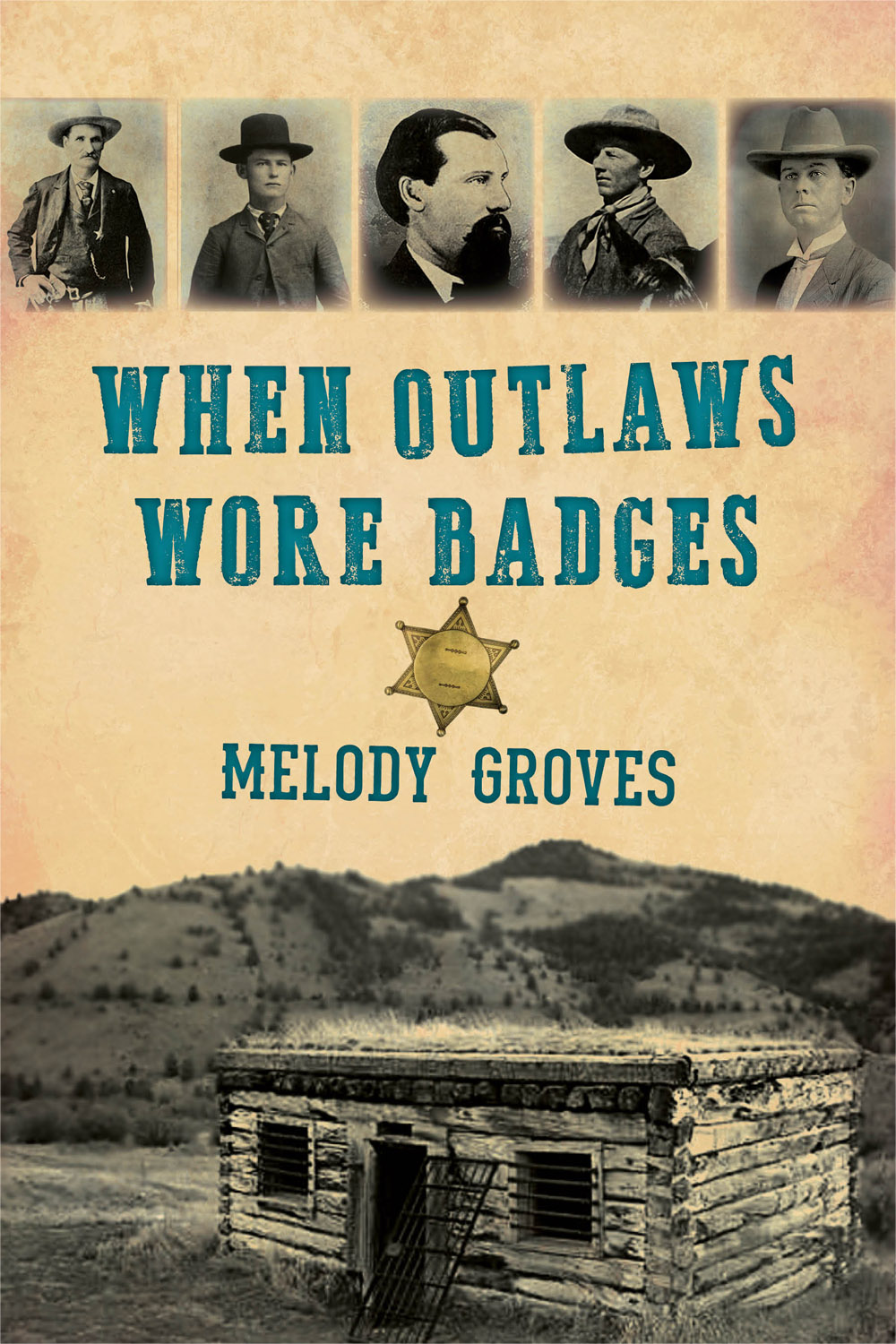

New Mexico native Melody Groves loves Western history. Enchanted by the area where she grew up, as a youngster she and her family explored ghost towns, which sparked her imagination. Horses, tumbleweeds, the sky, and characters who impacted the Western mystique charged through her mind. They still do. Winner of numerous writing awards, she writes for True West , Enchantment Magazine , New Mexico Magazine , and Wild West , among others. In 2018, she won the prestigious National Press Women Award for her True West Magazine article on Albuquerques first town marshal, who got himself (justifiably) hanged.

A TWODOT BOOK

An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Blvd., Ste. 200

Lanham, MD 20706

www.rowman.com

Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK

Copyright 2021 by Melody Groves

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020950357

ISBN 978-1-4930-4803-8 (paper : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-4930-4804-5 (electronic)

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

CONTENTS

Guide

A VOLUMINOUS THANK YOU TO:

Myke Groves, photography acquisition assistant

Marc Ferguson, curator at Daltons Hideout, Meade, Kansas

Rough Riders Museum, Las Vegas, New Mexico

Judy Avila, Joyce Hertzog, Phil Jackson, Dennis Kastendiek, Kathy Wagoner, Bill Pinnell, editorial assistants

TWO MEN... BOTH HEELED... STAND IN THE MIDDLE OF THE street... legs apart... eyes squinting into steely stares. Hands hover over the butts of their holstered revolvers.... And then... a twitch... an eye tic... like lightning, hands slap leather. Hammers pull back. Point.

Bang!

Bang!

One walks away.

Lawman or outlaw? Black-hatted villains and white-hatted good guys of the Old West walked the streets of our imagination. Hollywood drew a convenient line in the Western dirt, differentiating between the two. But in reality, at times it was difficult, if not impossible, to distinguish who was who. Shadowy faces roamed the West.

In his biography Wyatt Earp: The Life behind the Legend (1997), Casey Tefertiller writes that Earp became a vigilante, a marshal, and an outlaw all at the same time. Convinced that law no longer protected law-abiding citizens in Tombstone, Arizona Territory, Earp moved outside legal boundaries to bring what he considered order and justice to a chaotic situation.

His dilemma was nothing new in the West. Mid- to late nineteenth-century frontier areas, including mining camps such as Deadwood, found themselves reinventing laws and society. Cow towns such as Wichita, Abilene, and Dodge City faced a constant barrage of change, resulting in instability. Even small commercial towns such as Lincoln, New Mexico Territory, exemplified these chaotic times. So, is it any wonder the lines between lawman and outlaw were blurred?

Westerners blazed away at each other with Colt revolvers, Winchester carbines, and double-barrel shotguns. Gunfighters... shootists... pistoleros... leather slappers... gunmen... buscaderosmen of the West exposed themselves to peril by wearing badges, robbing people, or associating with dangerous men in dangerous places. Sometimes, they did it all at once. And which side of the badge the gunfighters were on made it legal or not.

Unlike Old West movies, where the outlaw was always a grizzled, mean, and murdering road agent and the lawman was a calm, steely-eyed, honest man, the reality was that the two types were very much alike. Some were known to have been good men, such as Bat Masterson, Heck Thomas, and Bill Tilghman. But even a young Bill Tilghman was once charged with stealing, and so was Wyatt Earp.

What the lawmen and outlaws had in common, besides their gun handling, was the willingness to risk their lives to enforce the law or to commit a crime. There were various types of lawmen in the Old West. There were US marshals, selected by the attorney general; sheriffs elected to office by county residents; marshals chosen by the city council; and deputies, constables, rangers, and peace officers.

Many lawmen received no pay other than a percentage of any money that those they arrested might be fined, or the collection of bounties on the heads of wanted men. This often led them to have second jobs, or to sometimes use their badges in establishing protection rackets or other crimes. Pay was often very low for those who did make a salary, and their duties included tasks that many felt were beneath them, such as keeping the street clean, or in the case of US marshals, being responsible for taking the federal census and distributing presidential proclamations. Often their work consisted of boring tasks punctuated by moments of high drama and accentuated by deadly confrontation.

Young man, lay away your gun. Remember poor Yarberry.

SANTA FE DAILY NEW MEXICAN, FEBRUARY 10, 1883

HOLLYWOOD COULDNT WRITE AN OLD WEST CHARACTER BETter than Milton J. Yarberry, Albuquerques first town marshal. Trigger-happy Yarberry met his demise at the end of a hangmans noose, when, on February 9, 1883, he uttered his final words, Gentlemen, you are hanging an innocent man, before being jerked to Jesus.

H E S TARTED Y OUNG

Yarberry, who started life probably as John Armstrong in Walnut Ridge, Arkansas, in 1849, turned to crime at an early age. Using several aliases over his lifetime, as a young teenager, he began his criminal career by killing a man over a land dispute. On the run, he changed his name for the first time, claiming he could not bring shame to his family. In 1873, he killed a man in Helena, Sharp County, Arkansas, and again fled.

According to all contemporary reports, Yarberry was not a handsome man. Long, lanky, and slightly stooped, he stood six foot three without boots and walked with a peculiar, loose-jointed, shambling gait. A long, crane-like neck supported his small, poorly-developed head, with its dark hair and mustache, restless cold grey eyes, straight thin nose, and mouth expressing chiefly cunning and cruelty. One reporter, after interviewing him, concluded he lacked the mentality to distinguish between a legal and an illegal act.

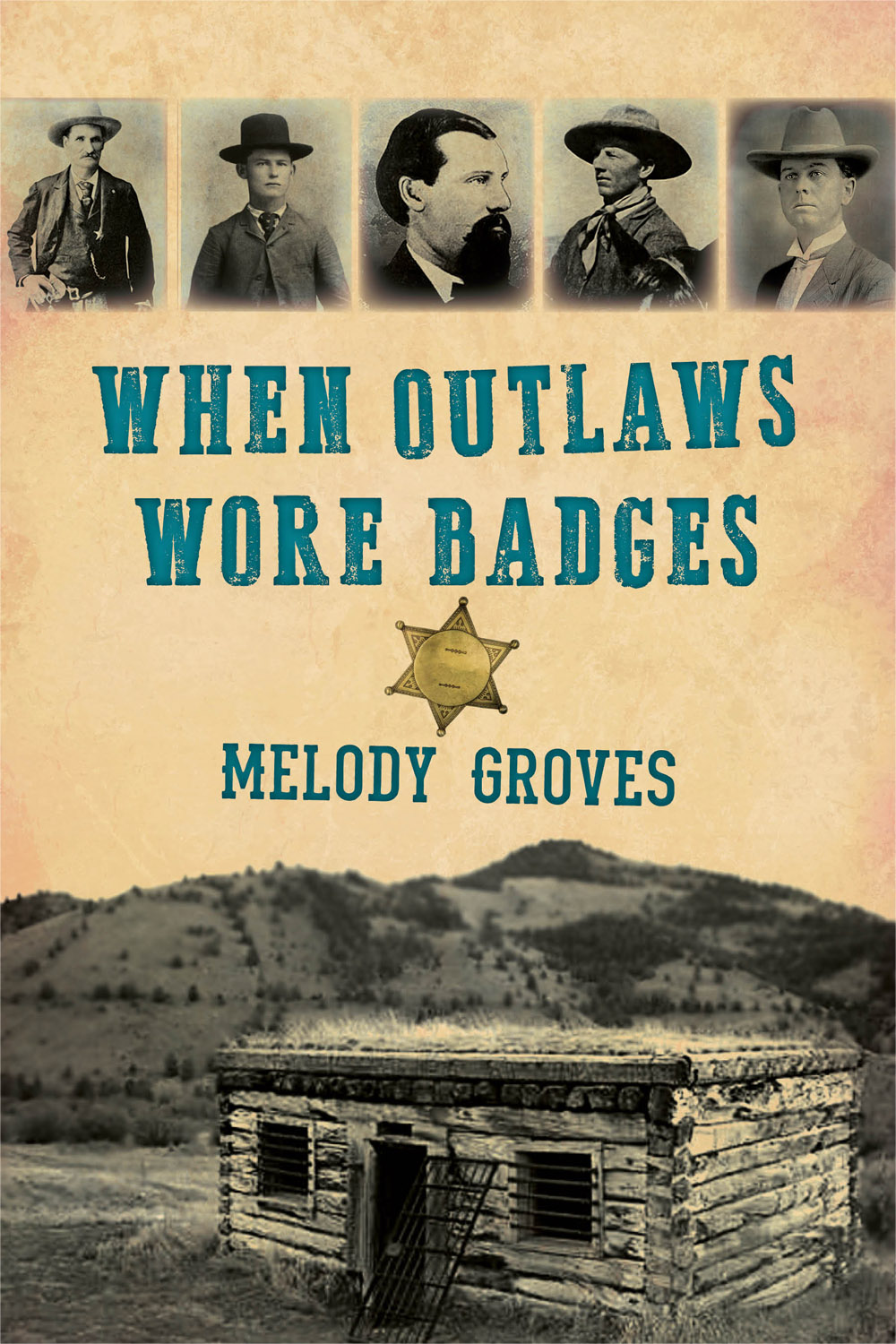

Albuquerques first Town Marshal was hanged in 1883.

AUTHORS COLLECTION

R USTLING

During the 1870s, Yarberry rode with outlaws Dave Rudabaugh and Mysterious Dave Mather (who also associated with Billy the Kid) and beginning in 1873, operated mostly in southern Missouri and northern Arkansas. The three formed a cattle- rustling outfit, engaged in several robberies, and were implicated in the murder of a well-known rancher in Arkansas.

Yarberry and the boys hightailed it to Texas and scattered. For a time, Yarberry settled in Texarkana, the rendezvous of more criminals than any spot in the West, but moved when he met a man he suspected of being a bounty hunter. Understandably nervous, Yarberry, convinced someone was trailing him, always looking over his shoulder, thought a man walking behind him was a detective. He shot and killed him. It turned out the victim was an inoffensive traveler.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.