My deepest thanks to all the contributors in this anthology and to colleagues and friends: Mathapelo Mofokeng, Leanne Brady, Huda Tayob, Thandi Loewenson, Julie Nxadi, Uhuru Phalafala, Masande Ntshanga, Ben Verghese, Lerato Maduna, Sindiswa Busuku, Imraan Coovadia, Mads Brgger, Nadia Davids, Robert Berold, Neelika Jayawardane, Robyn Khoza, Rustum Kozain, Lidudumalingani, Kagure Mugo, Khanyo Mjamba, Yewande Omotoso, Lindokuhle Nkosi, Nick Mulgrew, Ratik Asokan, Rejoice Modiba, Barbara Kilian, Kwanele Sosibo, Natasha Himmelman, Ben Stanwix, Dominique Edwards, Kimathi Mafafo, Hugh Byrne, Sivan Zeffertt, Anna van der Ploeg, Amber Moir and Inga Somdyala.

Heartfelt thanks as well to Annie Olivier and the wonderful team at Jonathan Ball Publishers: Paul Wise, Janita Low, Patricia Mzimba, Nicole Duncan, Sean Robertson and Johan Koortzen, and to my family, for their love and support.

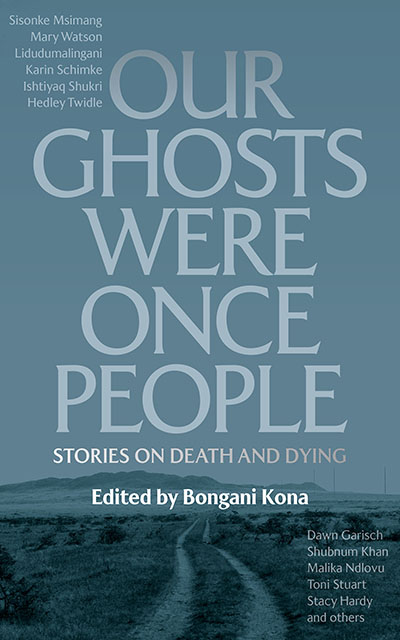

Introduction

W HEN WE GOT THE NEWS that my cousin Ys cancer had come back a second time, it didnt cross my mind that she would die. I thought she would survive it; she was only 40 years old, but the cancer had spread all over and her condition deteriorated rapidly. She died in the night-time, holding her mothers hand. This was weeks after the country had been placed on lockdown Alert Level 5, and because we couldnt travel, my mother and I watched the funeral on Zoom. This, as the old saying goes, is how we live now.

This has been a time of unremitting grief. People have lost loved ones, homes, jobs, and suffered all kinds of setbacks, large and small. At a time like this, the promise literature holds out to us is that were never alone. During a phone conversation in the early days of South Africas lockdown with the writer and audio producer Catherine Boulle, one of the contributors to this book, we discovered that wed each been turning to Svetlana Alexievichs Chernobyl Prayer: A Chronicle of the Future an oral history of the nuclear disaster in the Soviet Union in 1986 to make sense of the times. As we stared out onto the wide, empty streets from our respective homes, Alexievichs words resounded in our ears like a prophecy: We now find ourselves on a new page of history. The history of disasters has begun.

In one of the essays contained in this book, the novelist Ishtiyaq Shukri remembers sitting with friends at a coffee shop in central London days before the World Health Organisation declared coronavirus a global pandemic on 11 March 2020. Echoing the misplaced optimism of those early days, Shukri writes, consensus around the table was that the virus would probably be under control by June [2020]. That the number of Covid-19 deaths in South Africa, a year later, would total more than 50 000 (at the time of writing), was something that lay beyond the reach of our imaginations. Who would have foreseen that millions of us would live in a state of almost permanent low-grade anxiety and fear of contracting the virus and possibly dying from it?

While this is not a book about the pandemic, there has been no escaping its mark on our world. In April 2020, when my father was diagnosed with cancer and admitted to hospital, I couldnt travel home, Mary Watson writes in the essay which opens this collection, Neither Here nor There. Both Ireland and South Africa were in lockdown, and even if I could, it would have been irresponsible to travel ten thousand kilometres to visit a sick man in the middle of a pandemic.

The writers in this anthology wrestle with the idea of death and dying, seldom an easy task, and I am grateful to each of the contributors. In her breath-taking memoir, Men We Reaped , which chronicles the deaths of five black men, including her younger brother, Jesmyn Ward writes: To say this is difficult is understatement; telling this story is the hardest thing Ive ever done. But my ghosts were once people, and I cannot forget that.

Wards memoir shapes the heaviness of grief into something readers can find meaning in. This book attempts to do something similar.

In The Grief of Strangers, Lidudumalingani draws us into the world of Imiphanga , a radio show on Umhlobo Wenene that reads out death notices and that for years formed the background noise of his childhood. For the duration of the show, Lidudumalingani remembers, it seemed as if the world outside had paused, its shutters closed, at least to my mother. Shed always sit right in front of the radio, hunched over the table, listening, holding a space for the bereaved. Lidudumalinganis essay then leaps forward in time to our present age where the image of a lifeless body lying on the streets can be shared on social media even before loved ones hear of it.

The Missing Persons Task Team is a unit in the National Prosecuting Authority set up on the recommendation of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to trace the fate and whereabouts of those who were disappeared or went missing in political circumstances between 1960 and 1994, and tries to recover their remains. Our cases may be decades old, Madeleine Fullard, the head of the task team, writes in her essay, Investigative Pieces, but we are in a breathless race against time. Then later she writes: Most fragile and impermanent are the human beings. It is the families themselves, especially the mothers, who wither and die in the waiting.

Politics is what determines which lives are allowed to expire prematurely. In her essay charting the impact of the heroin trade in South Africas urban centres, Simone Haysom (Living as Ghosts Do) argues that the governments indifferent response has relegated heroin addicts to the realm of the living dead. Its maybe not too much of a stretch to say that many heroin addicts live as ghosts do haunting the highways, the cities, the abandoned small-town high street, the suburb, their families. Its not clear what they could do if they wanted to leave their phantasmal life behind, if they wanted to develop materiality, be seen again. The state offers almost no help to anyone in their situation who wants to get clean, or even just stable.

Elsewhere, Paula Ihozo Akugizibwe (How to Kill a Man) writes about learning the Israeli militarys street combat technique, Krav Maga. Only later in the essay does Akugizibwe reveal the tragedy propelling her obsession with self-defence. In The Pattern of Trees, the lone short story in this collection, Stacy Hardy explores the murder of women at the hands of men. By the time we meet Hardys protagonist, a forensic pathologist, shes already been murdered. She lies in a shallow grave, attempting to solve her own murder.

The other contributors in this collection explore subjects as varied as the ritual bathing of the body of the deceased and the ethics of killing small animals.

What consolation can literature offer in the face of such unending grief?

One of my favourite Raymond Carver stories, A Small, Good Thing, is a domestic tragedy that hinges on a breakdown in communication between a well-to-do woman named Ann and a baker who works 16 hours a day to earn a living. Ann orders a cake decorated with a spaceship under a sprinkling of stars for her sons birthday party but then doesnt turn up to pay and collect. That Monday, her soon-to-be-eight-year-old son, Scotty, is the victim of a hit-and-run while walking to school. The boy is rushed to hospital with what at first appear to be minor injuries shock, a mild concussion, some fluid in the lungs but later prove otherwise. He falls into a coma and days later, his last breath is puffed through his throat and exhaled gently through the clenched teeth.