T here is an eerie, sometimes pathetic, ofttimes beautiful urge that prevails in Black American lore, lyrics and literature. The impulse, simply put, is to tell the storyto tell ones own storyas one has known it, and lived it, and even died it.

From 1619, with the off-loading of nineteen Africans at Jamestown, Virginia, until this age of innocuous television series featuring Black characters, a large number of white writers have felt they were not only capable but called upon to write the Black persons story.

It is rather astounding that so many noninformed, or at best partially informed, yet otherwise learned personages have felt and still feel that although they themselves could not replicate the grunts, moans and groans of their Black contemporaries, they could certainly explain the utterances and even give descriptions, designs and desires of the utterers. Black Americans often have found themselves in disagreement with many who have cavalierly drawn their portraits.

Langston Hughes captured the protest in his poem Note on Commercial Theatre:

Youve taken my blues and gone

You sing em on Broadway

And you fixed em

So they dont sound like me.

Yes, you done taken my blues and gone.

You also took my spiritual and gone.

But someday somebodyll

Stand up and talk about me,

And write about me

Black and Beautiful

And sing about me,

And put on plays about me!

I reckon itll be

Me myself!

Yes, itll be me.

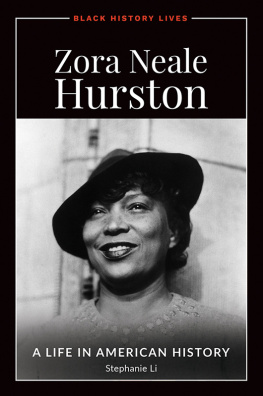

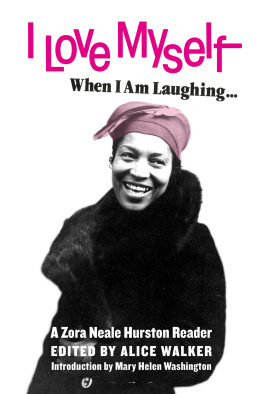

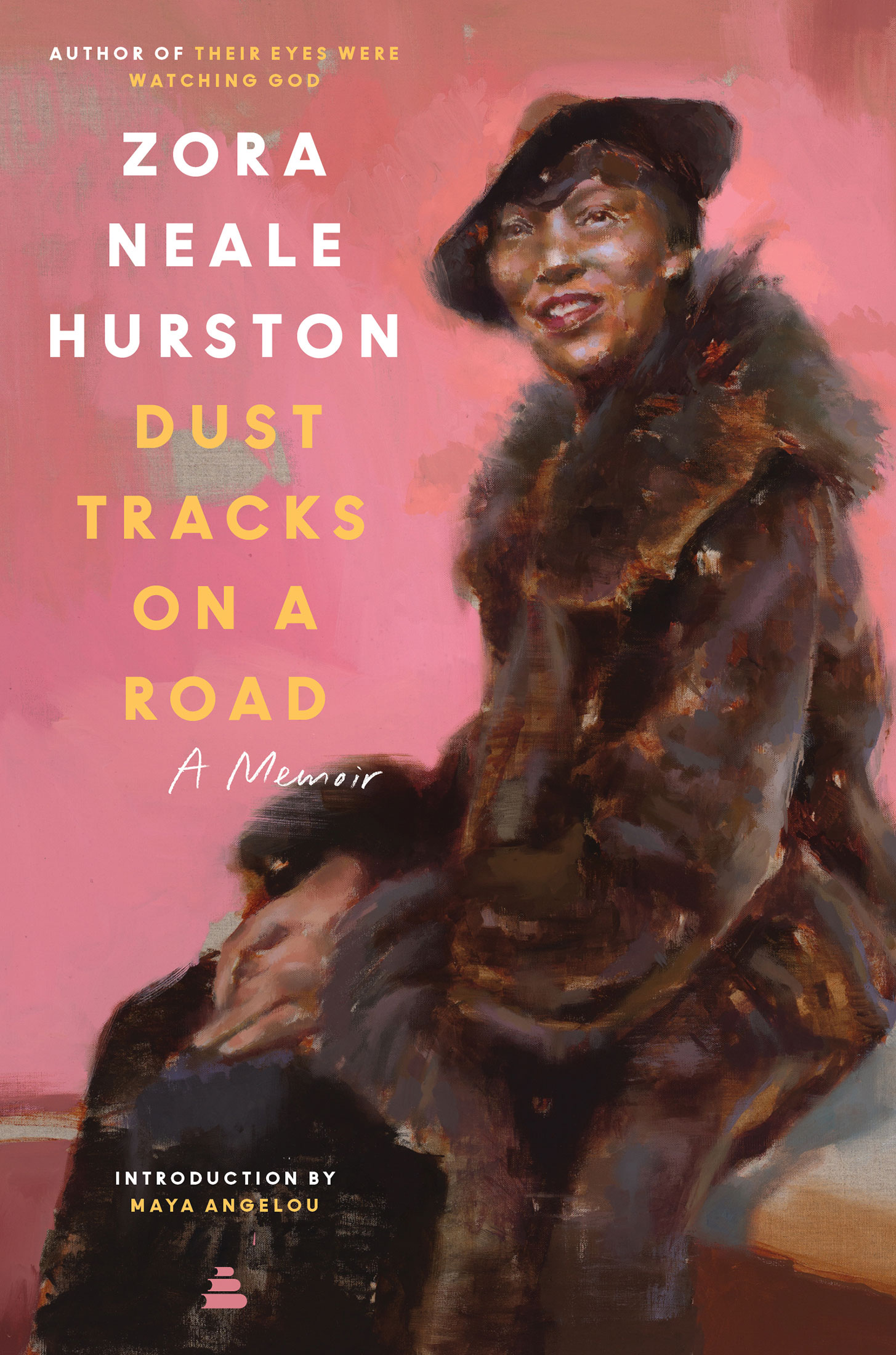

Zora Neale Hurston chose to write her own version of life in Dust Tracks on a Road . Through her imagery one soon learns that the author was born to roam, to listen and to tell a variety of stories. An active curiosity led her throughout the South, where she gathered up the feelings and sayings of her people as a fastidious farmer might gather eggs. When she began to write, she used all the sights she had seen, all the people she had encountered and the exploits she had survived. One reading of Hurston is enough to convince the reader that Hurston had dramatic adventures and was a quintessential survivor. According to her own account in Dust Tracks on a Road , a hog with a piglet and an interest in some food Hurston was eating taught the infant Hurston to walk. The sow came snorting toward her, and Zora, who had never taken a step, decided that the time had come to rectify her reluctance. She stood and not only walked but climbed into a chair beyond the sows inquisitive reach.

That lively pragmatism which revealed itself so early was to remain with Hurston most of her life. It prompted her to write and rewrite history. Her books and folktales vibrate with tragedy, humor and the real music of Black American speech. In a letter to a friend, she wrote that she wanted to show a Negro preacher who is neither funny nor an imitation puritan ramrod in his pants. Just the human being and poet he must be to succeed in a Negro pulpit. Thus, her first novel, Jonahs Gourd Vine . published in 1934, clearly told the story of John Hurston, her father, who could build houses, uproot trees, fight victoriously, love women and preach the color blue out of the sky.

Hurston was born in Eatonville, Florida, the only incorporated, all-Black town in America. Her father, with whom she rarely shared a peaceful hour, had been the towns alderman, three times its mayor, and had written many of the laws in the late 1800s, which are still observed in the 1990s.

In this autobiography Hurston describes herself as obstinate, intelligent and pugnacious. The story she tells of her life could never have been told believably by a non-Black American, and the details in even her own hands and words offer enough confusions, contusions and contradictions to confound the most sympathetic researcher.

Her mother, whom she seemed to have pitied but only glancingly loved, died when Hurston was nine years old. Her father remarried, and the antipathy between them was exacerbated by the presence and actions of a thick-skinned and malicious stepmother. Hurston found her first personal power at the expense of her fathers wife.

The primeval in me leaped to life. Ha! This was the very corn I wanted to grind. Fight! Not having to put up with what she did to us through Papa!If I died, let me die with my hands soaked in her blood. I want her blood, and plenty of it. That is the way I went into the fight, and that is the way I fought it.

She scratched and clawed at me, but I felt nothing at all. In a few seconds, she gave up. I could see her face when she realized that I meant to kill her. She spat on my dress, then, and did what she could to cover up from my renewed fury. She had given up fighting except for trying to spit in my face, and I did not intend for her to get away.

This puzzling book was written during 1940 and 1941 but for the most part deals with the early part of the twentieth century. Hurston, who claimed to have been born in 1901, but whose records show her birth year was a decade earlier, most certainly lived through the race riots and other atrocities of her time. However, she does not mention even one unpleasant racial incident in Dust Tracks on a Road . The southern air around her most assuredly crackled with the flames of Ku Klux Klan raiders, but Ms. Hurston does not allude to any ugly incident.

Her silence over these well-known issues gives rise to many questions: Why did Hurston write Dust Tracks on a Road? Whose song was she singing? And to whose ears was she directing her melody? Is this book a tale or a series of tales meant to appease a white audience? Does Hurston mean to show herself as a sleeping princess who will awaken to grandeur with the slightest kiss from a white prince?

Hurston does imply that the nicest people she met in her youth were whites who showed her kindness. It was a white man, who, discovering her mother in labor, delivered Hurston into the world and afterward took a proprietary interest in her. Hurston recalls how the kindly crusty old man took the eight-year-old Black girl fishing and gave her advice that might have been William Shakespeares from the mouth of a Faulknerian Polonius.

He called me Snidlits, explaining that Zora was a hell of a name to give a child.

Snidlits, dont be a nigger, he would say to me over and over. Niggers then on. Truth is a letter from courage. I want you to grow guts as you go along. So dont you let me hear of you lying. Youll get long all right if you do like I tell you. Nothing cant lick you if you never get skeered.

That was a knowledge not given to many southern Black girlsor boys for that matter. In fact, few southerners of any race or sexual persuasion would have deduced that the old white man meant anything other than dont be Black, if you possibly can, for your greater good and the general wealth and welfare of everyone, be or at least act white.

Two white women whom Hurston describes as gracious and beautiful gave her candies, clothes and books to read. She says of them:

They had shiny hair, mostly brownish. One had a looping gold chain around her neck. The other one was dressed all over in black and white with a pretty finger ring on her left hand. But the thing that held my eyes were their fingers. They were long and thin, and very white, except up near the tips. There they were baby pink. I had never seen such hands. It was a fascinating discovery for me. I wondered how they felt.

First thing, the ladies gave me strange things, like stuffed dates and preserved ginger, and encouraged me to eat all that I wanted. Then they showed me their Japanese dolls and just talked.

Is it possible that Hurston, who had been bold and bodacious all her life, was carrying on the tradition she had begun with the writing of Spunk in 1925? That is, did she mean to excoriate some of her own people, whom she felt had ignored or ridiculed her? The New Yorker critic declared the work a warm, witty, imaginative, rich and winning book by one of our few genuine grade A folk writers.