Contents

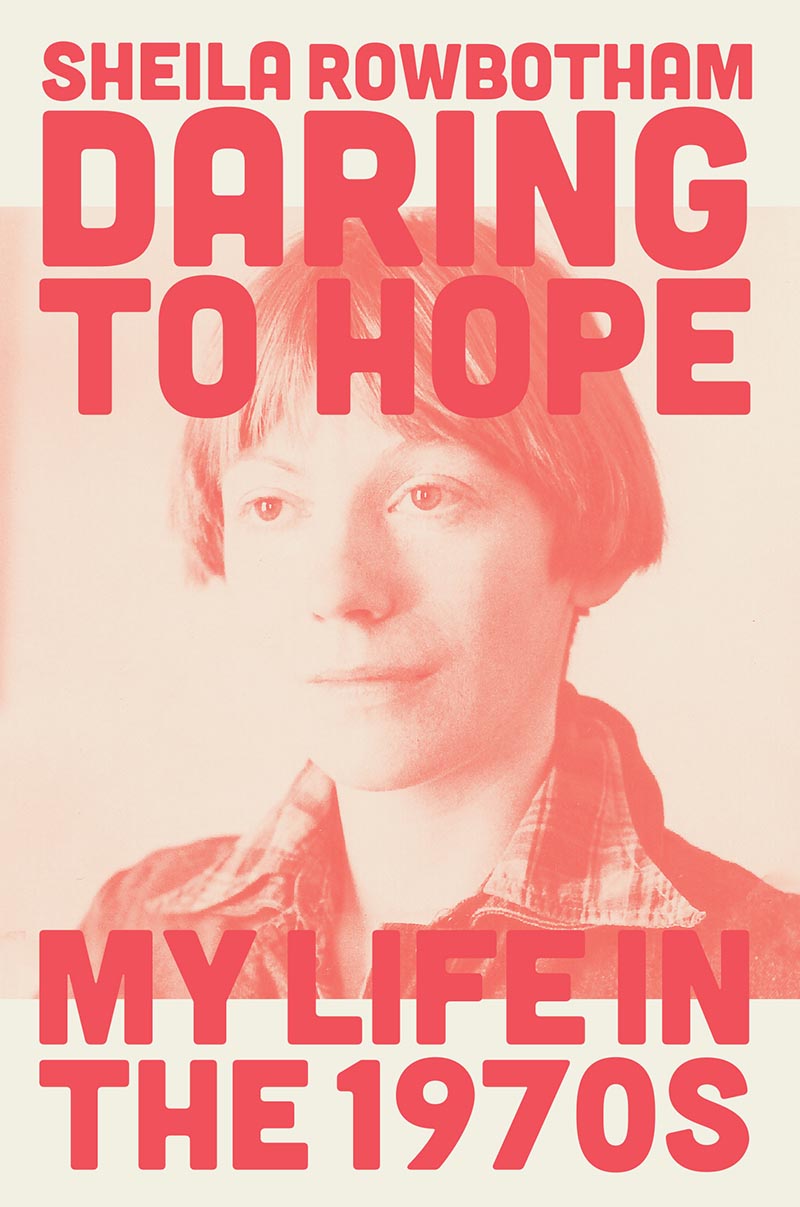

Daring to Hope

Daring to Hope

My Life in the 1970s

Sheila Rowbotham

First published by Verso 2021

Sheila Rowbotham 2021

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-389-2

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-391-5 (US EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-390-8 (UK EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Rowbotham, Sheila, author.

Title: Daring to hope : my life in the 1970s / Sheila Rowbotham.

Description: London ; New York : Verso, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Summary: In this powerful memoir, historian and feminist Sheila Rowbotham looks back at the womens liberation movement, left politics, and the vibrant, creative culture of a decade in which freedom and equality seemed a hairs breadth away. It is a riveting personal history of second-wave feminism from the front line Provided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021016503 (print) | LCCN 2021016504 (ebook) | ISBN 9781839763892 (hardback) | ISBN 9781839763915 (ebk)

Subjects: LCSH: Rowbotham, Sheila. | Feminists Great Britain Biography. | Feminism Great Britain History 20th century. | Second-wave feminism Great Britain.

Classification: LCC HQ1595.R69 A3 2021 (print) | LCC HQ1595.R69 (ebook) | DDC 305.42092 [B] dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021016503

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021016504

Typeset in Fournier by MJ & N Gavan, Truro, Cornwall

Printed in the UK by CPI Mackays

Contents

I am very grateful to the staff of the Womens Library at the London School of Economics, and most especially to Gillian Murphy, for sustained help in consulting my papers which are deposited there. While some of these are generally accessible, others have yet to be catalogued. I also looked at material in Marilyn Porters papers, Feminist Archive South in Special Collections at the University of Bristol, and I thank the staff there too for help and permission to quote from the material. Emilyn L. Brown, Archivist at the Schlesinger Library for the History of Women in America, Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Harvard University, kindly arranged for copies of my letters to Rosalyn Baxandall to be sent to me. I am indebted to her and to those who copied them. Ros Delmar gave me vital assistance on the contents of Red Rag, which is now online.

I thank Leo Hollis for all the hard work he put into editing the manuscript and for his many helpful comments. Thanks also to all the workers at Verso who assisted in its production and to my wonderful copy editor Tim Clark. Paul Atkinson, Lola Dickinson, Nigel Fountain, Riley Linebaugh and Stefanie Pixner read the first draft and sent valuable feedback. Faith Evans, my agent, played a crucial role in encouraging me to persist and has given me unstinting help with the manuscript. My loving comrade Mike Richardson listened to countless stories and lived amid much tumult as I tussled with the writing. He also played a vital part in assembling the photographs.

I consulted the following to check details: Sally Alexander, Franoise Barret-Ducrocq, Phineas Baxandall, Yvonne Beecham, Joanna Bock, Caroline Bond, Stella Dadzie, Rosalind Delmar, Sue Finch, Linda Gordon, Bruce Green, Catherine Hall, Hermione Harris, Roberta Hunter-Henderson, Temma Kaplan, Helena Kennedy, Radha Kumar, Alex May, Sue OSullivan, Ursula Owen, John Pipal, David Phillips, Hugo Radice, Janet Re, Jo Robinson, Dione Rowbotham, Marsha Rowe, Ann Scott, Lynne Segal, Sue Sharpe, Laureen Shaw, Barbara Taylor, Carole Turbin, Lisa Vine and Hilary Wainwright.

I thank Juliet Ash for sending me correspondence with David Widgery, and Carole Turbin for returning my letters to her. I am also grateful to Gillian Slovo for permission to quote from the letters of Ruth First, to Harriet Ward for those of Dora Russell, to Phineas Baxandall for those of Ros Baxandall, and to the other correspondents I could trace whose letters are also cited from my archive at the Womens Library, LSE.

For permission to reproduce images I am grateful to Paul Atkinson, Phineas Baxandall, Chandan (Sally) Fraser, Bruce Green, Jo Nesbitt, James Swinson, Humphry Trevelyan, Jaap van Ginneken and Lisa Vine, also to Tony Wickert for his shot of me laughing at the 1970 Womens Liberation Conference and to Julian Richman, who made the still from Liberation Films A Womans Place.

Every effort has been made to find all copyright holders. The author and publisher will be glad to recognise any holders of copyright who have not been included above.

In 1970 I was twenty-six and working on my first book. I was a socialist and part of the emerging British womens liberation movement, supporting gay liberation, revolt in the trade unions and resistance to racism. Demands for economic and social resources and claims for recognition and respect were being asserted by many groups who had been either sidelined or outcast. The term liberation extended democracy beyond voting; it meant opposing all forms of inequality and hierarchy. It carried too a fragile vision of what else might be a fusion of collective and individual freedom.

My socialism had been greatly influenced by two historians, Dorothy and Edward Thompson, whom I had met when I was nineteen. After the Soviet suppression of the uprising in Hungary in 1956 they had been involved in the New Left, an international network of groups that broke with the Communist parties. Among the many books and papers in their home I found old copies of the socialist humanist journal The New Reasoner. I was drawn to its ethos of cooperative creative potential, and squirrelled away Edwards phrases in my head: Enduring militancy is built not upon negative anxieties, but

We hopeful younger leftists, having not experienced travail or defeats, were inclined to seize upon this more beyond. The seventies saw a great surge of rebellion and dissent that spanned politics, culture and personal life. By 1979 these idealistic hopes were beleaguered, yet still resilient.

Subsequent defeats were to occlude the radical impetus of the seventies and to caricature its aims and intentions as wild, wacky and wrong. In retrieving what I remember from the time and disentangling the threads of my own thoughts and feelings, my intention is not to nudge towards nostalgia for the past. Without idealizing what those of us on the left and the womens movement did, I simply want to reassert the depth and scope of what we attempted, in the hope that future generations will be able to uncover these strands and go beyond them.

A conundrum in writing history is how to convey what tends be taken for granted because it is not mentioned. Yet what is implicit is vital for comprehending how things come about. Thus it is important not only to uncover what happened, but to look at how circumstances were inwardly perceived and regarded. In writing a personal testimony I have tried to express how it seemed at the time, using the terms and ideas current in the seventies. I have drawn on what I and others said or wrote during the decade and have correlated my own memories with letters as well as printed evidence.