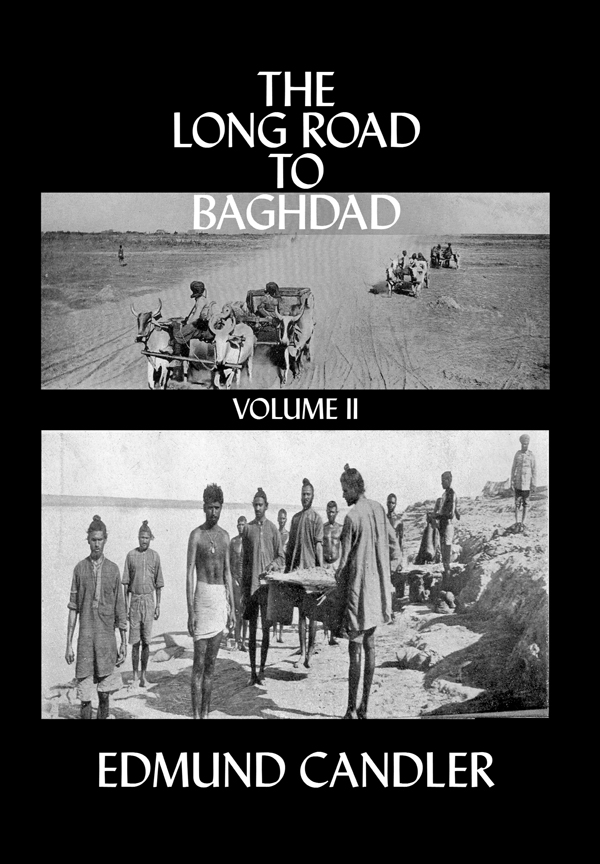

First published in 1919 by Cassell & Co.

This edition first published in 2009 by

Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada

by Routledge

270 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Cassell & Co 1919

Printed and bound in Great Britain

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 10: 0-7103-1150-8

ISBN 13: 978-0-7103-1150-4

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent. The publisher has made every effort to contact original copyright holders and would welcome correspondence from those they have been unable to trace.

Chapter XXV

The Advance

T HERE was nothing very memorable in the first days of the advance, but it was a relief to be breaking new ground. There was an exhilaration in moving on. We seemed to have spent interminable years cooped up at El Orah, Falahiyeh, and Arab Village. Each of these camps repeated the other so exactly that time came to be reckoned, not by locality so much as by phases of emotion, or absence of emotionthe anxiety and depression of the long months before the fall of Kut, the dead monotonous resignation of the hot weather afterwards, when the sun and flies contributed the physical element to our mental Avernus, and then the relief of being cool and comfortable again and the prospect of becoming something, or doing something, and ceasing to be an altogether derelict army.

Was it to be Baghdad or Kut? Nobody knew. Most of us thought Kut, though the Tigris was very broad, and the defences at Sannaiyat so indefinitely repeated in the rear of the position that unless we could turn the place by a crossing upstream the breaking through would cost more than it was worth. After all, the value of Kut now was more sentimental than strategical, and whatever shape our policy or strategy took, the immediate and ultimate objective was to contain, or kill, as many Turks as we could, or in current metaphor to pull our weight.

We were conscious during the lull before the advance that the two Army Corps on the Tigris, with a bare 18,000 Turkish rifles opposed to them, were not pulling their weight. The cold weather was advancing, and the rainy season, which, if severe, might be almost equivalent to immobilisation. There were signs of impatience at home, uneasiness in India. In the public eye Mesopotamia had become a sink, a backwater; our troops had lost moral, we were for ever marking time. But it is the proof of a strong commander not to be hustled by impatience or the mistrust that grows out of long inaction. Many a campaign has been lost by concession to the spirit of restlessness. But Maude chose his own time; nor did he communicate it. If Force D was not pulling its weight, it was because it was still in the training stage. Sinews were being developed. We had to create the staying-power that would carry us on after the first lap or two of the advance. This in the form of material and supplies; for the Army Commander had decided that no move should be made until we had accumulated a seven days reserve at Sinn.

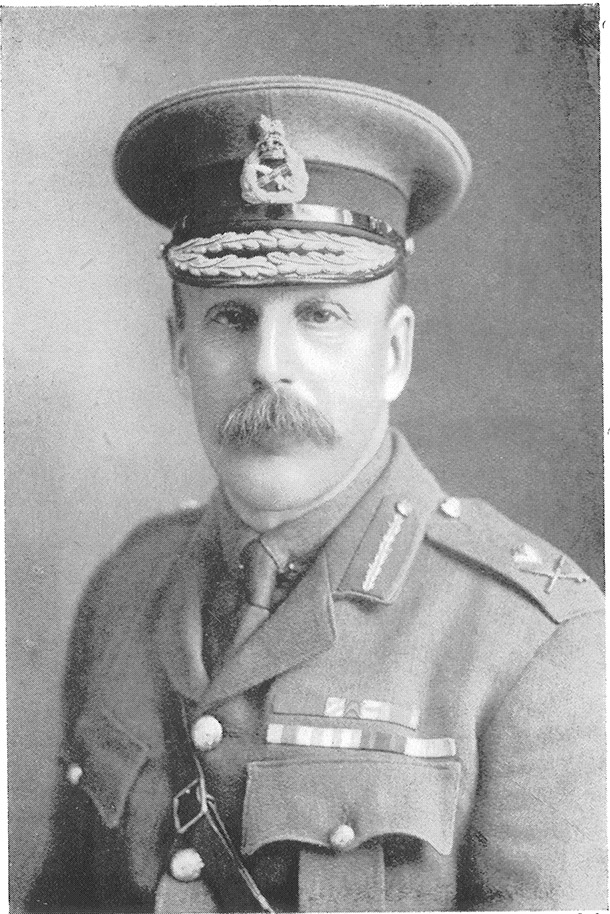

For the moment an organiser was needed more than a strategist or tactician; Maude was all three. In this connection I may quote a Staff Officer whose opinion carries weight everywhere in the Army. There are three things necessary for carrying on a campaign, he said. You want the fighting man whose genius is strategy and tactics; and you want the man who understands everything about Staff work; but these may be wasted without the brain for organisation and the interior economy of the army. I dont think I had ever struck a man who combined two of these qualities, certainly not three, until I met Maude.

Ones first impression of the Army Commander was modesty, repose, confidence, strength. One gradually realised the thoroughness and single-mindedness of the man, the far vision, the minute application to detail. He was a master of detail. He had his eye all the while on the ultimate end and on everything that concerned the immediate means to itsupply, transport, operations, intelligence, the psychological factors. In every branch of Staff work he was the inspirer and director. The reconstruction of the fighting machine, the breaking up of the Turks force on the Tigris, called for qualities which when found in combination amount to genius. In the dark days we prayed for a great man; and he was on the spot. General Maude might have been born for the task. His whole life was a preparation for it. The large vision was a gift; the discipline, method and single-mindedness were the outcome of the training his character had imposed on himself. I have heard his quiet strength compared to a flood, but it was a flood canalised. He had the concentration that is the first essential of greatness. He was not to be diverted by side issues. His one thought was to crush the Turk.

When we occupied Sinn on May 20th, after the Turks had evacuated it, our forward posts at Magasis, The Pentagon, and Imam Ali Mansur on the right bank were eleven miles upstream of the Sannaiyat position on the left, where the Turkish lines intercepted navigation on the river. Consequently, to supply our troops in the Sinn area a light narrow gauge (2 ft. 6 in.) railway was built from the advance base at Sheikh Saad to a point within the Sinn position lying between the Dujaila and Sinn Aftar Redoubts. This line was afterwards carried on to Imam Ali Mansur, though it was not opened for traffic until we were securely established on the Hai. It was then pushed on to Atab. A glance at the skeleton map will suggest what would have been gained in mobility and in the saving of transport if we could have established river communication up to Magasis. Sinn railway station was only three and a half miles from the river; Magasis Fort was on the river bank; yet freight was discharged from steamers at Sheikh Saad, twenty miles distant by rail. This entailed the upkeep of thousands of horses, mules, carts and Ford vans. It doubled our land transport in a country where there was no grazing, no local purchase to depend on, no fuel, and where everything, even the water for the blockhouses on the line of communications, had to be carried up from Sheikh Saad. For this makeshift single line did not suffice to feed the troops at Sinn, much less to deliver the seven days supplies which had to be accumulated there before the army could advance with any certainty of being fed.