Copyright 2012 by The Curators of the University of Missouri

University of Missouri Press, Columbia, Missouri 65201

Printed and bound in the United States of America

All rights reserved

5 4 3 2 1 16 15 14 13 12

Cataloging-in-Publication data available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-8262-1995-4

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.

Jacket design: Kathyrn Landis

Interior design and composition: Jennifer Cropp

Printing and binding: Thomson-Shore, Inc.

Typefaces: Geneva, Bebas Neue, Minion

(electronic ISBN: 978-0-8262-7294-2)

DEDICATED TO ALL OF THE WOMEN WHO HAVE TAKEN THEIR PLACES IN THE GREAT AMERICAN POLITICAL DRAMA

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

My thanks to all of the people who generously gave recollections to this work. You provided insight and detail into Mary Louise Smith's leadership that is not available elsewhere. A list of the people who were interviewed is in the bibliography.

The Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library generously contributed to the research through a research grant.

Mary Louise Smith's papers are housed at the Louise-Noun-Mary Louise Smith Iowa Women's Archives, University of Iowa. Curator Kren M. Mason has gone far beyond any reasonable expectations helping with every phase of this work, including reading and commenting on an early version of it. My thanks to her and her staff.

Archival materials also came from: Minnesota Historical Society Archives; Cornell University Archives; Arizona State University Archives; Western Historical Manuscript Collection at Columbia, Missouri; Ronald Reagan Presidential Library; and George H.W. Bush Presidential Library. I did not have the pleasure of visiting these research facilities, but I am grateful to the archivists and librarians who kindly responded to my requests.

My thanks to the volunteers and organizers of the North Coast Redwoods Writer's Conference in Crescent City, California, the South Coast Writers Conference in Gold Beach, Oregon, and the Flathead River Writers Conference in Whitefish, Montana.

My thanks to Louise Noun, Tom Morain, Joe Anderson, Hal Chase, and Richard, Lord Acton for reading an early draft of the first chapter. Later in the process, Judy Lonning, Jean Williams, Larry Anderson, Rich Eychaner, and Richard Thaxton read sections of this work. In addition, The Eureka (California) Writers Group also read parts of this work. If there was a Republican in the writers group, she or he did not reveal it. I thank them for their good will and perceptive comments. Gail Slaughter and Harry Lowther diligently read most of the manuscript. I thank everyone for their comments and suggestions.

I am grateful to the wonderful and patient staff at the University of Missouri Press. I appreciate your professionalism and your goodwill. John Brenner, Sara Davis, Dwight Browne, Beth Chandler, and Pippa Letsky made suggestions that resulted in a better work. Working with you has been a great pleasure.

Maggie Schenken and Bill Schenken, my children, have patiently listened to the story of this biography for most of their lives. They have been encouraging and enthusiastic over each development. Thank you, Maggie. Thank you, Bill.

And of course, my thanks to Mary Louise Smith for the hours she spent narrating her story.

INTRODUCTION

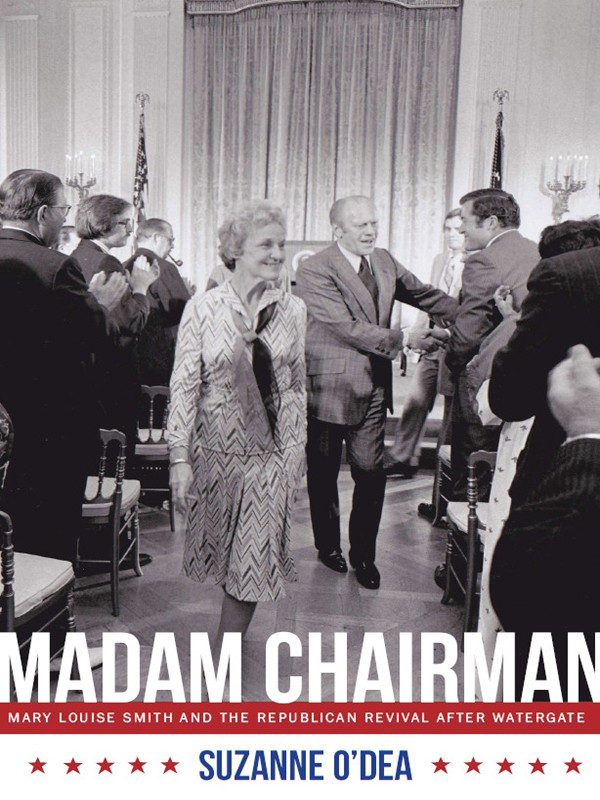

Thousands of delegates to the 1976 Republican National Convention greeted friends and milled around the floor of the Kemper Arena, Kansas City, Missouri. Representatives of President Gerald Ford's camp and of Ronald Reagan's camp vied for the delegates that would give their candidate the winning margin in the quest for the presidential nomination. Reporters searched for a new angle on the story. It was the party's first convention since Richard Nixon resigned from the presidency in disgraceand for the first time in the nation's history, a woman had organized a major party's quadrennial presidential nominating convention.

Organizing the convention had begun more than eighteen months earlier. It was a Herculean task complicated by Reagan's challenge to Ford for the party's nomination. Accusations that convention organizers had not treated the two campaigns equally plagued party chairman Mary Louise Smith and her staff for months and would continue until a nominee was chosen. In addition, new campaign finance laws restricted funding sources for the convention and implemented new restrictions on convention organizers, causing them to worry about unwittingly making illegal decisions. With all the planning finally over, convention officials had gathered on the stage, ready to begin four days of speeches, pageantry, and politics.

The woman who had navigated through this political maelstrom, Mary Louise Smith, stood at the podium with a gavel in her hand. For almost two years she had served her party as its chairman. For most of that time her critics had consoled themselves with the hopes that she would soon be gone. But there she stood. She had survived by developing programs and strategies to keep the party aliveto keep it from declining into a minor party, a third party. She had succeeded. The convention delegates, the candidates, and the press on the floor below her testified to it. They had not traveled to Kansas City for a funeral; they had come to choose their nominee for president.

Smith loved conventions. The people, the ceremony, the political celebrities, the receptions, and the excitement invigorated her. She had attended the 1964

Mary Louise Smith reveled in the art and science of putting together a get-out-the-vote effort, of creating new approaches to old conundrums, of working with the people who made their ways to the great American pastime of running the nation. No political race was too local or too small-time for her. And neither was she intimidated by running the national party organization. She was a politician, all the way through.

When Smith first entered politics, she had no issue, no goal, not even a candidate. A friend had invited her to a meeting of the local Republican women's group. There, in small-town rural Iowa, Smith discovered organizational politics, the work of phone calls, door-to-door canvassing, speaking at ladies' luncheons, and selling Republican-themed jewelry to fund it all. Even though such ground-level elementary work may not seem a good preparation for national leadership, one could argue that it provided the political education a national party leader needed in 1974.

When the demands of the national party chairmanship required more technical expertise than she had, Smith recruited the best people she could find and gave them the freedom to experiment, knowing that experiments regularly include failure. The group of creative, innovative political risk-takers she assembled won some and lost some, but they knew that, regardless of the immediate outcome, Smith would provide them with the cover from criticism they needed to continue exploring options. By taking the heat (as more than one of her staffers noted), she gained their trust and their loyalty, of a quality that could still be appreciated almost twenty years after she left the chairmanship.

The RNC staff numbered about 150 men and women. At the core of her leadership team were five men: Gary Engebretson, Joe Gaylord, Eddie Mahe, Jr., Rodney Smith, and Richard Thaxton. In the following pages, they tell the stories of the late-night sessions, the risk-filled programs, and the courage Smith displayed as she led the party. These men repeatedly pointed to Smith's leadership as the source for the party's successes in 1975 and 1976. Perhaps the key success of that period was that the party did not devolve into a minor, third party. The men listed aboveas well as othersmaintain that it was Smith's work to rebuild the party that provided the foundation upon which her successor built and which Ronald Reagan used to win the presidency in 1980.

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.