First published in the United States and the United Kingdom in 2015 by

Overlook Duckworth, Peter Mayer Publishers, Inc.

NEW YORK

141 Wooster Street

New York, NY 10012

www.overlookpress.com

For bulk and special sales please contact ,

or to write us at the above address.

LONDON

30 Calvin Street, London E1 6NW

T: 020 7490 7300

E:

www.ducknet.co.uk

For bulk and special sales please contact ,

or write to us at the above address.

2014 John Launer

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-4683-1158-7

M Y INTEREST in Sabina Spielrein began through pure serendipity. For many years I was on the staff at the Tavistock Clinic in London, a major centre for psychological treatment in the United Kingdom. One of my regular tasks there was to run a management training day for people who were about to become qualified psychiatrists and psychologists. We usually spent most of the day doing an exercise in which they had to act as the boards of two imaginary mental health institutions. Over the years I had fun inventing the names of these institutions. For some time I called one of them The Spielrein Institute. I chose the name as a joke at least, I thought it was a joke. I took it from a real historical figure called Sabina Spielrein. Like many people, all I knew about her was that she was a patient of Carl Jung and had become his mistress. I knew that Sigmund Freud was somehow connected with her, and thought maybe she had been his patient too. I also liked the sound of her name, which I assumed was probably Viennese.

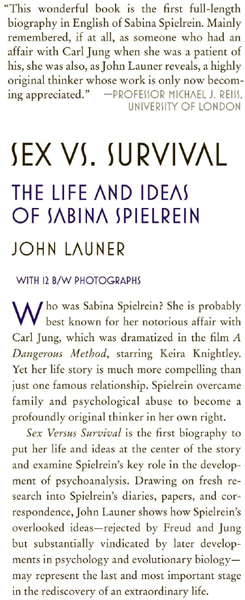

One day, I decided I should pay Sabina Spielrein the respect of finding out more about her. I read about her affair with Jung, and how Freud helped in a cover-up to protect him. Much had been written by Freudians attacking Jung over the whole business, by Jungians defending him, and by feminists wishing a plague on both their houses. It certainly seemed that Spielrein conducted herself with greater dignity and restraint than either of the men. Apart from reading about this episode, I discovered that Spielrein was a psychiatrist and psychoanalyst in her own right. I felt contrite at having used her name in a flippant way and decided to make amends by reading some of her professional articles. She wrote them in the first thirty years of the last century in German, French and Russian, though they were translated into English only in the 1990s. Her most significant paper was entitled Destruction as the Cause of Coming into Being. This was originally published in 1912 and was based on a lecture she had given the previous year in front of Freud and his circle in Vienna.

I can remember the moment I started to read the paper. I almost fell out of my chair with astonishment. I felt I was reading something written a century ahead of its time. It seemed that Sabina Spielrein had anticipated many of the biological and psychological ideas of our own age. These included the need for understanding the mind in terms of its evolution, and the role of the reproductive drive in human psychology. From a modern perspective, there were flaws in her argument. All the same, I was shocked to discover that her theory was completely rejected indeed mocked by those who heard it at the time. I found it incomprehensible that these ideas had disappeared into oblivion. I started to read her letters, diaries and other scholarly papers. These deepened my respect for her as an original thinker. In all the existing books and articles about her, I could find no account that did her full justice. A number of writers argued that she was underestimated as a thinker, but this was in the context of showing how Freud, Jung and others adapted some of her ideas. No one had ever re-examined her life and ideas as a whole, or properly challenged the way she was marginalised in the history of psychology. I closed down the imaginary Spielrein Institute and became interested in the real Sabina Spielrein. I started to collect materials about her, intending to write a book about her one day, perhaps in old age. The announcement of a Hollywood movie about her, A Dangerous Method, caught me by surprise. I pulled together a small self-published volume about her in time for the launch of the movie, hoping that it might gain some attention for her ideas rather than the imaginative scenes of her sex life that were the main attraction of the film. This led to a commission to write the present book.

I am pleased to have completed the book before reaching old age, but as a result I have had to do so while working full time. This would have been entirely impossible without the indulgence and love of my wife Rabbi Lee Wax and our children Ruth and David. I want to express my enormous gratitude to them. This acknowledgement must precede all those that follow.

Although I know some German and French and a minuscule amount of Russian, I have been dependent on prodigious amounts of translation into English carried out by dedicated friends who were able to do this better than I. These were Tom Carnwath, Jens Fll, Andrew Levy, Judith Prais, Annie Swanepoel and Neil Vickers. All of them offered helpful reflections on the material they translated and on earlier drafts of the book, especially Neil Vickers who was able to draw on his extensive knowledge of psychoanalytic history. I am immensely grateful for the many hours of work they put in simply through friendship.

At an early stage of my interest in Spielrein, two tolerant editors allowed me to summarise her story in print for a medical readership: Christopher Martyn at the Quarterly Journal of Medicine and Fiona Moss at the Postgraduate Medical Journal. Subsequently, Melvin Bornstein at Psychoanalytic Inquiry asked me to elaborate in print on Spielreins ideas about sex and sexuality and what these might mean from a modern perspective. These were important steps towards developing my understanding of Spielrein and her relevance to contemporary thought. After I wrote my original short book about Spielreins life and ideas, I was invited by Bernadette Wren and David Bell to give a presentation about her to a scientific meeting at the Tavistock Clinic. Subsequently Joan Raphael-Leff asked me to do the same to the academic faculty of the Anna Freud Clinic. The intelligent questions and challenges I faced at those events helped me to hone my ideas considerably. Arising out of the Tavistock meeting, I set up a small seminar group there, to explore the potential connections between evolutionary theory and psychotherapy of the kind that Spielrein pointed towards. The members of that seminar group are Jim Hopkins, Graham Music, Michael Reiss, Daniela Sieff, Annie Swanepoel and Bernadette Wren, with Sebastian Kraemer as a corresponding member. Our monthly meetings, email dialogues and exchanges of papers have played an important part in my attempt to evaluate Spielreins theories. The use of the outstanding library at the Tavistock Clinic has been a great boon, and I greatly appreciate the help I have had from its staff.

While I was writing my original version of the book, I corresponded with a number of evolutionists and psychoanalysts to check out my ideas, and received useful comments from them. Apart from those already mentioned, they include Gillian Bentley, Linda Brakel, Jim Chisholm, Helena Cronin, Martin Miller, Aine Murphy and Randolph Nesse. When the movie about Spielrein was released, Sarah Ebner at the London