Bibliographical Note

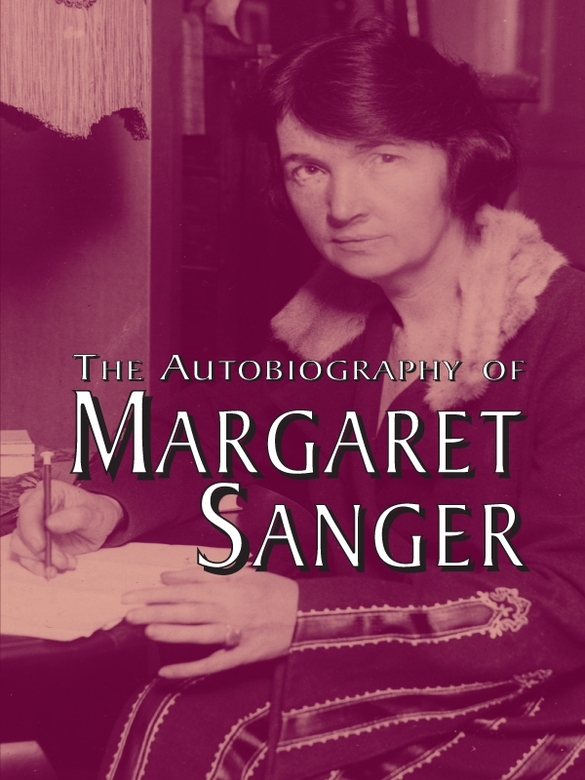

This Dover edition, first published in 1971 and republished in 2004, is an unabridged and unaltered republication of the work originally published by W. W. Norton & Company, New York, in 1938 under the title Margaret Sanger: An Autobiography.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

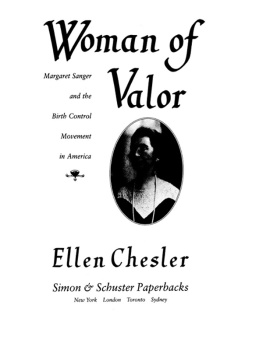

Sanger, Margaret, 18791966.

[Margaret Sanger, an autobiography]

The autobiography of Margaret Sanger / Margaret Sanger.

p. cm.

An unabridged and unaltered republication of the work originally published by W. W. Norton & Company, New York, in 1938 under the title Margaret Sanger: an autobiographyVerso t.p.

Includes index.

9780486120836

1. Margaret Sanger, 18791966. 2. Birth controlUnited StatesBiography. 3. Women social reformersUnited StatesBiography. 1. Title.

HQ784.S3S36 2004

363.96092dc22

2004041366

Manufactured in the United States of America Dover Publications, Inc., 31 East 2nd Street, Mineola, N.Y. 11501

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

My thanks are due especially to Rackham Holt for her discerning aid in organizing material and for her untiring and inspired advice during the preparation of this book; as well as to Walter S. Hayward whose able assistance has helped to make the task lighter.

In the course of preparing this narrative many books have been consulted. I trust their authors will agree with me that a bibliography in a personal history is cumbersome and accept a general but none the less grateful acknowledgment.

My admiration has always gone out to the person who can put himself in print and set down for historical purposes an exact record of his honest feelings and thoughts, even though they may seem to reflect upon many of his friends and helpers. I have not in this story hurt any one by intent. Because its thread has, of necessity, followed dramatic highlights, many people who played prominent parts have not been mentioned. These I have not forgotten, nor those numerous others who made smaller offerings. Some have pioneered in their special fields and localities; some have given generously and unfailingly of their financial help; some have volunteered in full measure their time and efforts as officers and Committee members; some have fought and labored by my side throughout the years; some have stepped in for only a brief but significant role. Although on the outskirts of the army, it is to these last as well as to those in the vanguard that the advance has been made. And particularly do I wish to thank those co-workers and members of the various staffs whose contributions can in no way be measured by their duties, and whose indefatigable, loyal devotion has been a bulwark of strength to me at all times.

It has been impossible to carry out my sincere desire to give personal and individual recognition and expression of gratitude to all. Neither a history of the birth control movement nor the part I have taken in it could be complete, however, did I not pay tribute to the integrity, valiance, courage, and clarity of vision of the men and women who, year after year, maintained their principles, and never swerved from them in a cause which belongs to all of us.

Chapter One

FROM WHICH I SPRING

Where shall I begin, please your Majesty? he asked. Begin at the beginning, the King said, very gravely, and go on till you come to the end: then stop.

LEWIS CARROLL

T HE streets of Corning, New York, where I was born, climb right up from the Chemung River, which cuts the town in two; the people who live there have floppy knees from going up and down. When I was a little girl the oaks and the pines met the stone walks at the top of the hill, and there in the woods my father built his house, hoping mothers congestion of the lungs would be helped if she could breathe the pure, balsam-laden air.

My mother, Anne Purcell, always had a cough, and when she braced herself against the wall the conversation, which was forever echoing from room to room, had to stop until she recovered. She was slender and straight as an arrow, with head well set on sloping shoulders, black, wavy hair, skin white and spotless, and with wide-apart eyes, gray-green, flecked with amber. Her family had been Irish as far back as she could trace; the strain of the Norman conquerors had run true throughout the generations, and may have accounted for her unfaltering courage.

Mothers sensitivity to beauty found some of its expression in flowers. We had no money with which to buy them, and she had no time to grow them, but the woods and fields were our garden. I can never remember sitting at a table not brightened with blossoms; from the first spring arbutus to the last goldenrod of autumn we had an abundance.

Although this was the Victorian Age, our home was almost free from Victorianism. Father himself had made our furniture. He had even cut and polished the slab of the big marble-topped table, as it was always called. Only in the spare room stood a piece bought at a storea varnished washstand. The things you made yourself were not considered quite good enough for guests. Sometimes fathers visitors were doctors, teachers, or perhaps the village priest, but mostly they were the artisans of the communitycabinet makers, masons, carpenters who admired his ideas as well as shared his passion for hunting. In between tramping the woods and talking they had helped to frame and roof the house, working after hours to do this.

Father, Michael Hennessy Higgins, born in Ireland, was a nonconformist through and through. All other men had beards or mustachesnot he. His bright red mane, worn much too long according to the family, swept back from his massive brow; he would not clip it short as most fathers did. Actually it suited his finely-modeled head. He was nearly six feet tall and hard-muscled; his keen blue eyes were set off by pinkish, freckled skin. Homily and humor rippled unceasingly from his generous mouth in a brogue which he never lost. The jokes with which he punctuated every story were picked up, retold, and scattered about. When I was little they were beyond me, but I could hear my elders laughing.

The scar on fathers forehead was his badge of war service. When Lincoln had called for volunteers against the rebellious South, he had taken his only possessions, a gold watch inherited from his grandfather and his own fathers legacy of three hundred dollars, and had run away from his home in Canada to enlist. But he had been told he was not old enough, and was obliged to wait impatiently a year and a half until, on his fifteenth birthday, he had joined the Twelfth New York Volunteer Cavalry as a drummer boy.

One of fathers adventures had been the capture of a Confederate captain on a fine mule, the latter being counted the more valuable acquisition to the regiment. We were brought up in the tradition that he had been one of three men selected by Sherman for bravery. That made us very proud of him. Better not start anything with father; he could beat anybody! But he himself had been appalled by the brutalities of war; never thereafter was he interested in fighting, unless perhaps his Irish sportsmanship cropped out when two well-matched dogs were set against each other.