First printed for private distribution 2021

Kerr Publishing Pty Ltd

Melbourne, Victoria

ABN 64 124 219 638

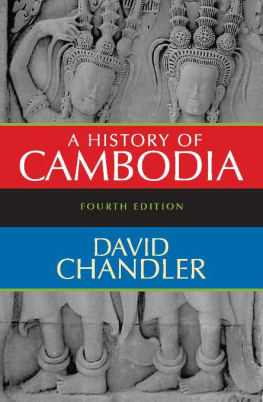

2021 David Chandler

This book is copyright. Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, or under Copyright Agency Ltd rules of recording, no part may be reproduced by any means. The moral right of the author has been asserted.

ISBN 978-1-875703-47-0 eBook

ISBN 978-1-875703-46-3 PoD (Print on Demand)

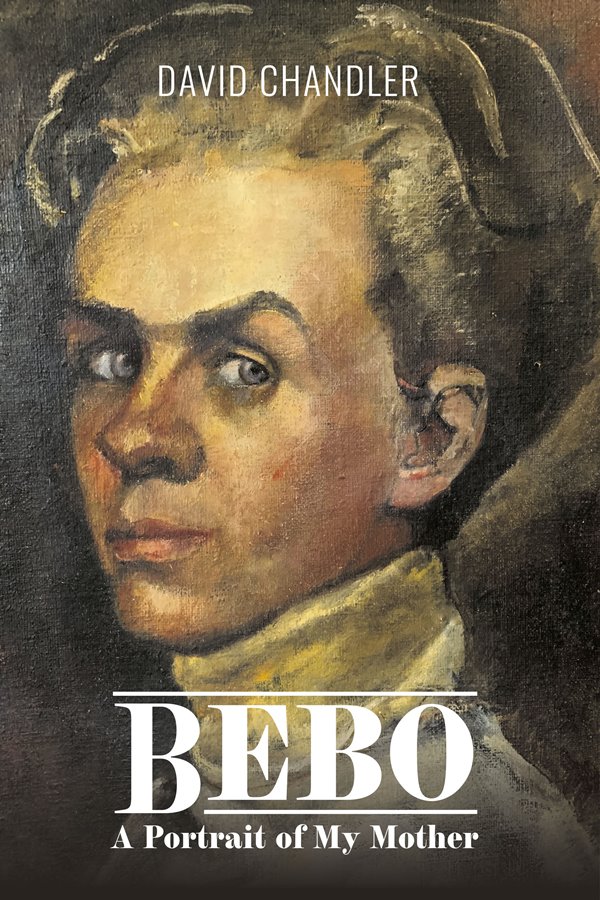

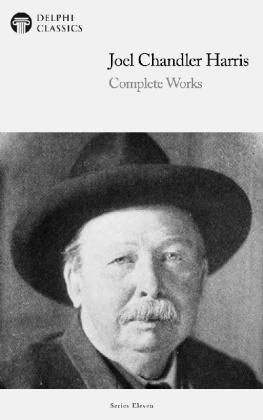

Cover photograph: Bebo, self portrait oil on canvas 1934

Cover and book design: Paul Taylder of Xigrafix Media and Design

National Library of Australia PrePublication Data Service:

Introduction

F amily names can often be confusing. My mother, christened May Margaret Gabrielle Chanler in 1897, added a d to her name when she married my father Porter Chandler in 1924. Hardly anyone who knew her called her Gabrielle, a name that she used only as a signature. Instead she was known throughout her life by her nickname, Bebo, derived from the Italian word bebolina meaning little pigeon, bestowed on her, it seems, by an Italian nursemaid in Rome when she was very young.

This book is about a person I loved, whose company I enjoyed and whom Ive been told I resemble in many ways. Ive written it because I was curious to learn more about a life that I felt was intrinsically interesting and partly concealed from view like the lives of many women of Bebos generation. Once I got started, I found that I had many helpful documents to work with. Finally, making sense of the sources and examining my mothers life in a narrative format appealed to me as a historian.

For several years there was a sense of urgency to the project because Id put off writing until I was seventy-six years old. Eleven years later, Im the only one left among Bebos descendants who can remember what she was like.

When I finished writing, I was eager for my wife, our children and Bebos younger descendants who never knew her to encounter her in these pages.

Inevitably, perhaps, this book will also tell the story of my parents thirty-four-year marriage and what they brought to it from their backgrounds, their childhoods and their parents. I need to stress that events in my fathers admirable, far more fully documented life crop up often in what follows but the focus for this project has kept me from writing the full-scale biography that he may well deserve.

Once my own memories kick in around 1938 what follows will be a narrative of my life up to Bebos death twenty years later. My three siblings also have roles to play in the memoir but I will try to keep Bebo on centerstage.

The principal documentary sources that I use are letters that Bebo wrote and received between 1908 and her death. Hundreds of them are housed in the New York Historical Society where my father deposited family papers in 1974. Several of the letters that she wrote to her mother before 1940 are in the Margaret Chanler collection in the Houghton Library at Harvard. My aunt Hester Pickman, Bebos older sister, presented me with a cache of Bebos letters in 1977 and more recently I located more than a hundred others among my fathers papers.

Many of the letters that people wrote to Bebo have been useful in what follows but I will be privileging the ones that she wrote herself. They have a lively, recognizable voice and a remarkably consistent point of view. She recognized this consistency in 1956 when she wrote to Hester: Re-reading my old letters has made me terribly self-conscious. I see myself (when we decide on the final disposal of family letters) saying to myself, I havent changed at all!

I regret that the letters she wrote to Porter when he was overseas in North Africa in 194243 were lost when the ship that was carrying among other things Porters footlocker in the summer of 1943 was torpedoed and sank. In his own letters from North Africa, which he collected in 1974, he remarks that Bebos letters to him were always enlightening and often pungent. They undoubtedly contained more information about the ebb and flow of her daily life than those she wrote at this time to Hester and her mother. They would certainly have enriched what follows.

Sadly, I saved only one of the letters that she wrote to me between 1947 when I went off to boarding school and 1958 when she died. These were the years of our greatest rapport and her letters were fun to read.

I also realize that the letters Ive used, even at their best, can only give snapshots of Bebo, the addresses where she was living and the days when they were written. Snapshots can be misleading sources for making sense of an entire life, for as Kathryn Hughes has perceptively written, Far from being the full picture of someones personality, letters provide an angled glance, as distorting as those fun house mirrors that you used to find at the end of piers. This is particularly true in what follows because I base so much of the book on Bebos letters to only three recipients: her husband, her mother and one of her sisters. Each of them required a different angled glance.

A second invaluable documentary source for my memoir consists of the medical records that were assembled in 1937 and again in 1953 when Bebo was a patient in what was originally known as the Bloomingdale Hospital in White Plains, NY. She was suffering on both occasions from what used to be called nervous breakdowns. She was a patient at the hospital for nine months in 1937 and for three months in 1953. I visited her in 1953 but her 1937 stay at the hospital, when I was only four, left a blank space in my childhood and in my knowledge of her life. This blank space was for many years a source of intellectual bafflement and concern for me. I simply didnt know what had happened in these hospitalizations, although my mother often said that the treatment shed received had been humane and helpful.

I requested a copy of Bebos medical records in 2010, and after they had been reviewed by staff at the Presbyterian Hospital (the successor to Bloomingdale) they were released to me a few months later. They contain many penetrating comments by psychiatrists about Bebo and her afflictions as well as several of her own characteristically frank, perceptive self-assessments. Bebos was an examined life, analyzed by herself and by several sympathetic, trained observers. Because Bebo was so vulnerable on both occasions the medical records were often saddening to read.