All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address Westview Press, 2465 Central Avenue, Suite 200, Boulder, Colorado 80301. Find us on the World Wide Web at www.westviewpress.com.

Westview Press books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the United States by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut St., Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 255-1514, or e-mail .

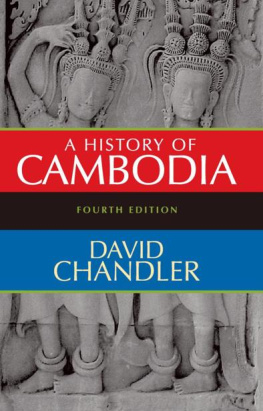

PREFACE TO THE FOURTH EDITION

Im grateful to Steve Catalano of Westview Press for encouraging me to prepare this edition of a book that was first published in 1983. Mr. Catalano is the latest in a series of talented and helpful editors at Westview who have worked with me on this book. Im also grateful to Kay Mareia, the project editor, and to Tom Lacey for his assiduous and helpful copyediting. Like the previous editions, this one is dedicated to my children.

The structure and the general approach of the book remain unchanged, but I have revised to reflect the valuable research that has been published since the 3rd edition appeared in 2000. I refer especially to the pioneering work of the Greater Angkor Project, Claude Jacques, Christophe Pottier, Ashley Thompson, and Michael Vickery. In the rest of the book I have tried to keep abreast of significant new scholarship. The closing pages, which deal with events since 2000, benefit from several visits to Cambodia and from discussions with many people including Erik Davis, Youk Chhang, Penny Edwards, Kate Frieson, Steve Heder, Don Jameson, John Marston, Un Kheang, and Kim Sedara.

After almost a half-century of being interested in Cambodia, I have contracted many other intellectual debts which its a pleasure to acknowledge. The deepest ones are to my wife, Susan, who first encouraged me to write this book, and to the late Paul Mus, who inspired my first two years of graduate study. Im grateful also to my former students Ben Kiernan and John Tully, and to a multitude of colleagues and friends, including Joyce Clark, Christopher Goscha, Anne Hansen, Alexander Hinton, Helen Jessup, Alexandra Kent, Charles Keyes, Judy Ledgerwood, Ian Mabbett, Milton Osborne, Saveros Pou, Lionel Vairon, John Weeks, and Hiram Woodward. The list could be much longer. As Paul Mus has tellingly written, People build themselves out of what is brought to them by friends.

In 2005 the third edition was ably translated into Khmer under the auspices of the Center for Khmer Studies. The interest that the translation aroused among Cambodians has been very gratifying to me, and I hope that some of the men and women who read the translation will become historians of Cambodia themselves.

Finally, these lines provide a sad but suitable occasion for me to mourn the recent loss of five amiable and talented compagnons de route: May Ebihara, Richard Melville, Ingrid Muan, Jacques Npote, and David Wyatt. I miss their friendship, their company, and their insights into Cambodias history and culture.

Melbourne, Australia

February 2007

David Chandler

1

INTRODUCTION

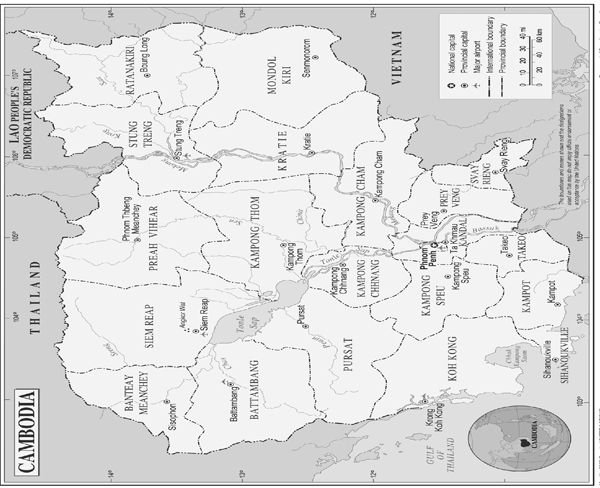

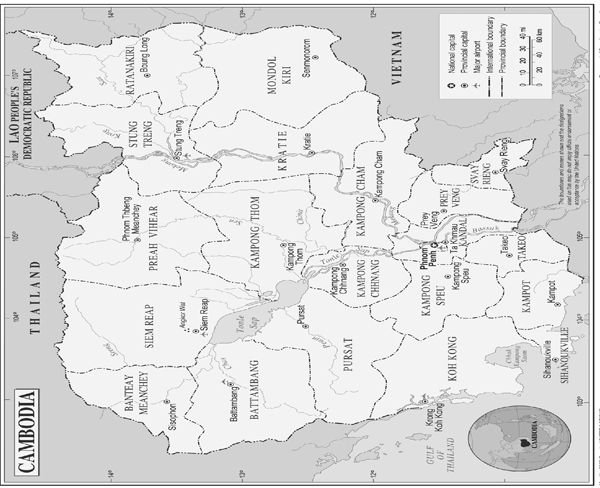

This book will examine roughly two thousand years of Cambodian history. through 5 carry the story up to the end of the eighteenth century; the remaining chapters deal with the period between 1794 and 2007.

One reason for writing the book has been to close a gap in the historiography of Southeast Asia. No lengthy history of Cambodia has appeared since the publication of Adhmard Leclres Histoire du Cambodge in 1914. through 7 has often been ignored even though it clearly forms a bridge between Angkor and the present.

The time has come, in other words, to reexamine primary sources, to synthesize other peoples scholarly work, and to place my own research, concerned mainly with the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, into the framework of a general history, with a nonspecialist audience, as well as undergraduates, in mind.

As it stands the book examines several themes. One of these has to do with the effects on Cambodian politics and society of the countrys location , has been crucial since the second half of the eighteenth century and has recently faded in importance. For over two hundred years, beginning in the 1780s, the presence of two powerful, antagonistic neighbors forced the contentious Cambodian elite either to prefer one or the other or to attempt to neutralize them by appealing to an outside power. Cambodian kings tried both alternatives in the nineteenth century. Later on, Norodom Sihanouk, Lon Nol, and Pol Pot all attempted the second; the regime of the State of Cambodia (SOC), formerly the Peoples Republic of Kampuchea, which lasted from 1979 until 1991, committed itself to the patronage of Vietnam. A UN protectorate (199193) neutralized the contending foreign patrons of Cambodia by removing it from Cold War rivalries. In the late 1990s Cambodia and Vietnam joined the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), and the Kingdom of Cambodia, established under that name in 1993, has so far avoided seeking a dominant foreign patron, although in recent years China has emerged as an increasingly important ally and benefactor of the regime.

Another theme, really a present-day one, has to do with the relationship of contemporary Cambodians to their past. The history of Angkor, after all, was deciphered, restored, and bequeathed to them by their French colonial masters. Why had so many Cambodians forgotten it, or remembered it primarily as myth? What did it mean to have the memories and the grandeur brought back to life, in times of dependence? What happened to the times between Angkor and the modern era? And in what ways are the post-Angkorean years, the colonial era, and what has happened since 1954 connected to these earlier periods? How are the revolutionary events of the 1970s to be remembered, taught, and internalized? There has even been pressure from the government to play down the teaching of Cambodian history as too controversial.

A third theme arises from the pervasiveness of patronage and hierarchies in Cambodian thinking, politics, and social relations. For most of Cambodian history, it seems, people in power were thought (by themselves and nearly everyone else) to be more meritorious than others. Older people were also ideologically privileged. Despite some alterations these arrangements remained unchanged between Cambodias so- The widespread acceptance of an often demeaning status quo meant that in Marxist terms Cambodians went through centuries of mystification. If this is so, and ones identity was so frequently related to subordination, what did political independence mean?

A Member of the Perseus Books Group

A Member of the Perseus Books Group