Burtyrki Books 2020, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

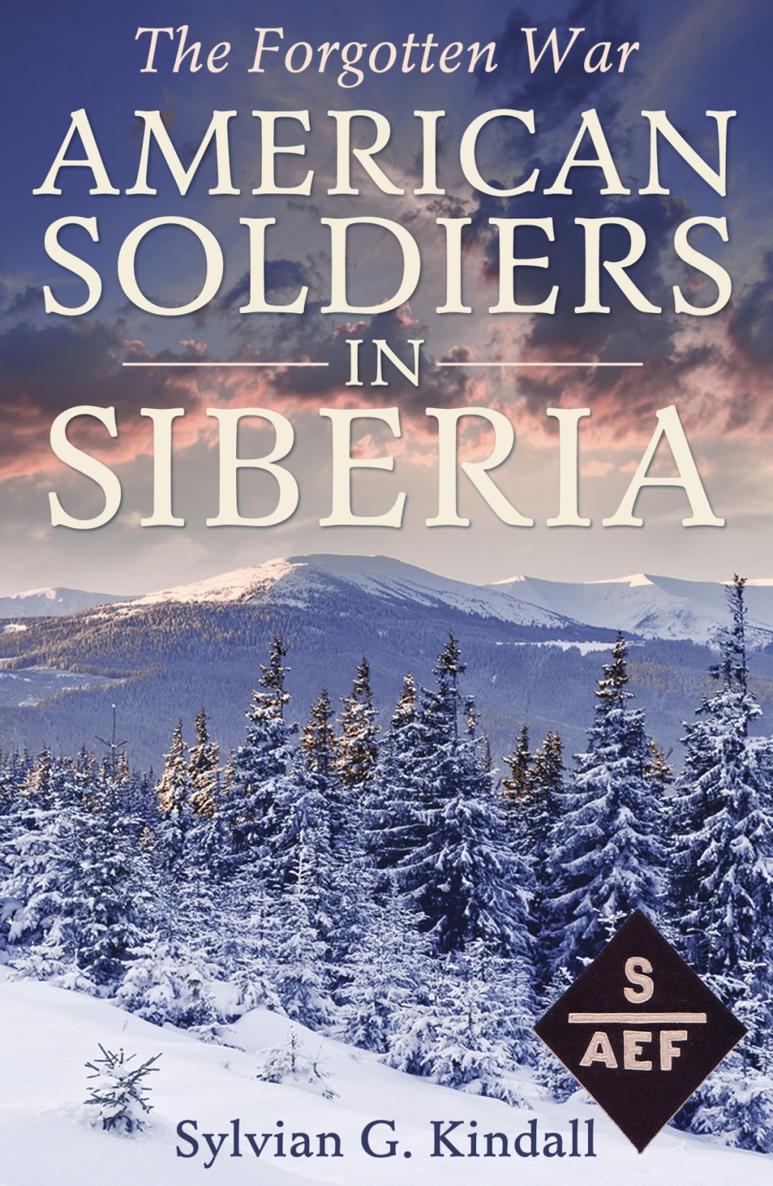

AMERICAN SOLDIERS IN SIBERIA

The Forgotten War

Sylvian G. Kindall

American Soldiers in Siberia was originally published by Richard R. Smith, New York, in 1945.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS

REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER

DEDICATION

* * *

DEDICATED

TO

THE FIGHTING FORCES IN THE PACIFIC

by one whose only distinction is that he happened to be the first American to qualify for the award of the Purple Heart for a wound received in a fight with the Japanese.

Sylvian G. Kindall

FOREWORD

American Soldiers in Siberia , by U.S. Army officer Sylvian G. Kindall recounts his experiences as a member of the American Expeditionary Force Siberia from 1918 to 1920. AEF Siberia was involved in the Russian Civil War in Vladivostok, Russian Empire, at the end of World War I following the October Revolution. The futility and unpreparedness of the mission is apparent throughout the book, as is the authors intense disdain for the Japanese troops, who were witnessed in repeated acts of violence against an unarmed citizenry.

President Woodrow Wilsons claimed objectives for sending troops to Siberia were both diplomatic and military. One major reason was to rescue the 40,000 men of the Czechoslovak Legions, who were being harassed by Bolshevik forces as they attempted to make their way along the Trans-Siberian Railroad to Vladivostok, and it was hoped, eventually to the Western Front. Another major reason was to protect the large quantities of military supplies and railroad rolling stock that the United States had sent to the Russian Far East in support of the prior Russian governments war efforts on the Eastern Front. Another stated reason was the need to steady any efforts at self-government or self defense in which the Russians themselves may be willing to accept assistance. At the time, Bolshevik forces controlled only small pockets in Siberia and Wilson wanted to ensure that neither Cossack marauders nor the Japanese military would take advantage of the unstable political environment along the strategically important railroad line located in this resource-rich region.

At the same time, and for similar reasons, about 5,000 American soldiers were sent to Arkhangelsk (Archangel), Russia by President Wilson as part of the separate Polar Bear Expedition.

The American Expeditionary Force Siberia was commanded by Major-General William S. Graves and eventually totaled 7,950 officers and enlisted men. AEF Siberia included the U.S. Armys 27 th and 31 st Infantry Regiments, plus large numbers of volunteers from the 13 th , 62 nd Infantry Regiments and 12 th Infantry Regiments of the 8 th Division, Graves former division command.

Armament included M1918 Browning Automatic Rifles (BAR) and Auto-5 shotguns/trench clearers, M1903 Springfield rifles and M1911 .45 caliber pistols, depending on their duties.

Although General Graves did not arrive in Siberia until September 4, 1918, the first 3,000 American troops disembarked in Vladivostok between August 15 and August 21, 1918. They were quickly assigned guard duty along segments of the railway between Vladivostok and Nikolsk-Ussuriski in the north.

Unlike his Allied counterparts, General Graves believed their mission in Siberia was to provide protection for American-supplied property and to help the Czechoslovak Legions evacuate Russia, and that it did not include fighting against the Bolsheviks. Repeatedly calling for restraint, Graves often clashed with commanders of British, French and Japanese forces, who also had troops in the region and who wanted him to take a more active part in the military intervention in Siberia.

The experience in Siberia for the soldiers was miserable. Problems with fuel, ammunition, supplies and food were widespread. Horses accustomed to temperate climates were unable to function in sub-zero Russia. Water-cooled machine guns froze and became useless.

The last American soldiers left Siberia on April 1, 1920. During their 19 months in Siberia, 189 soldiers of the American Expeditionary Force Siberia died from a variety of natural and battle-related causes. In comparison, the smaller American North Russia Expeditionary Force experienced 235 deaths during their 9 months of fighting near Arkhangelsk.

Chapter One INTRODUCTION

In Siberia the ten thousand soldiers serving in the American Expeditionary Force learned what Japanese treachery was like. This was more than twenty years before the sneak attack upon Pearl Harbor. In Siberia, too, these American soldiers often were the unhappy witnesses to outrageous brutality practiced by the Japanese soldiers upon the then helpless Russian peasants. The short fact is that in Siberia the typical combatant Japanese in his treatment of the Russians was the same gloating, sadistic, bloodthirsty brute that Americans have found him in the Pacific War. But, it seems, the experiences of American soldiers with Japanese treachery and bestiality in Siberia seldom have been heard about in the United States. This is mainly true, no doubt, because the Siberian expedition itself has always been something of a mysterythe army that the United States forgot to bring home, as it has been called. The quip is almost correct, for the Siberian force never returned as a body to the continental United States. The 31 st Infantry sailed down from Vladivostok to the Philippine Islands, and there remained. The 27 th Infantry likewise went to the Philippines, but later found a permanent home in Hawaii. The only other American groups in Siberia were a few service units. These were brought down to Manila and broken up, their personnel eventually drifting back to the United States or elsewhere as casuals.

But destiny has determined that the return from Siberia was not the end of experiences with the Japanese for either the 31 st or the 27 th Infantry. Fateful December 7,1941, found the first of these two regiments still on duty in the Philippines. All in haste it prepared to meet the brown hordes that soon were pouring ashore, transport-load after transport-load, along the beaches of Luzon. Later, it withdrew with the larger part of MacArthurs army into the high, jungle-grown mountains of Bataan Peninsula overlooking Manila Bay. All know the heartbreaking story that then followedweeks of heroic fighting against hopeless odds from the battered foxholes of Bataan, sickness, starvation, empty cartridge belts, and, then, despair and bitter surrender and the long death march down from the mountains to the prison camps outside Manila.

Similarly, on the Seventh of December the 27 th Infantry was at its own island station, Hawaii, and on the morning of that day from the porches of its barracks heard the beginning of the new war dropping down from the skies onto the area of Pearl Harbor, in the near distance. Some months later this regiment moved from its island home, and in steaming jungle places somewhere in the South Pacific it met with again and hunted down the same buck-toothed, yellow-bellied, stump-legged, slant-eyed, idiotic-grinning, wind-sucking, belly-grunting, skunk-stinking animal that, years before, it had learned to despise in Siberia. And now, as these lines are written, press dispatches mention the return of this regiment to the Philippines with the gallant forces of MacArthurs, from which place it was that both this regiment and the 31 st Infantry had sailed in 1918 upon the Siberian adventure.