Contents

Landmarks

Print Page List

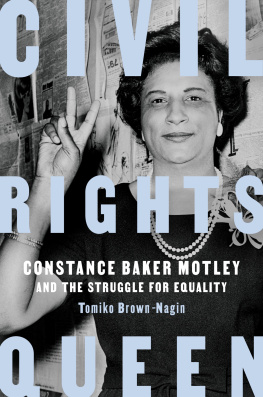

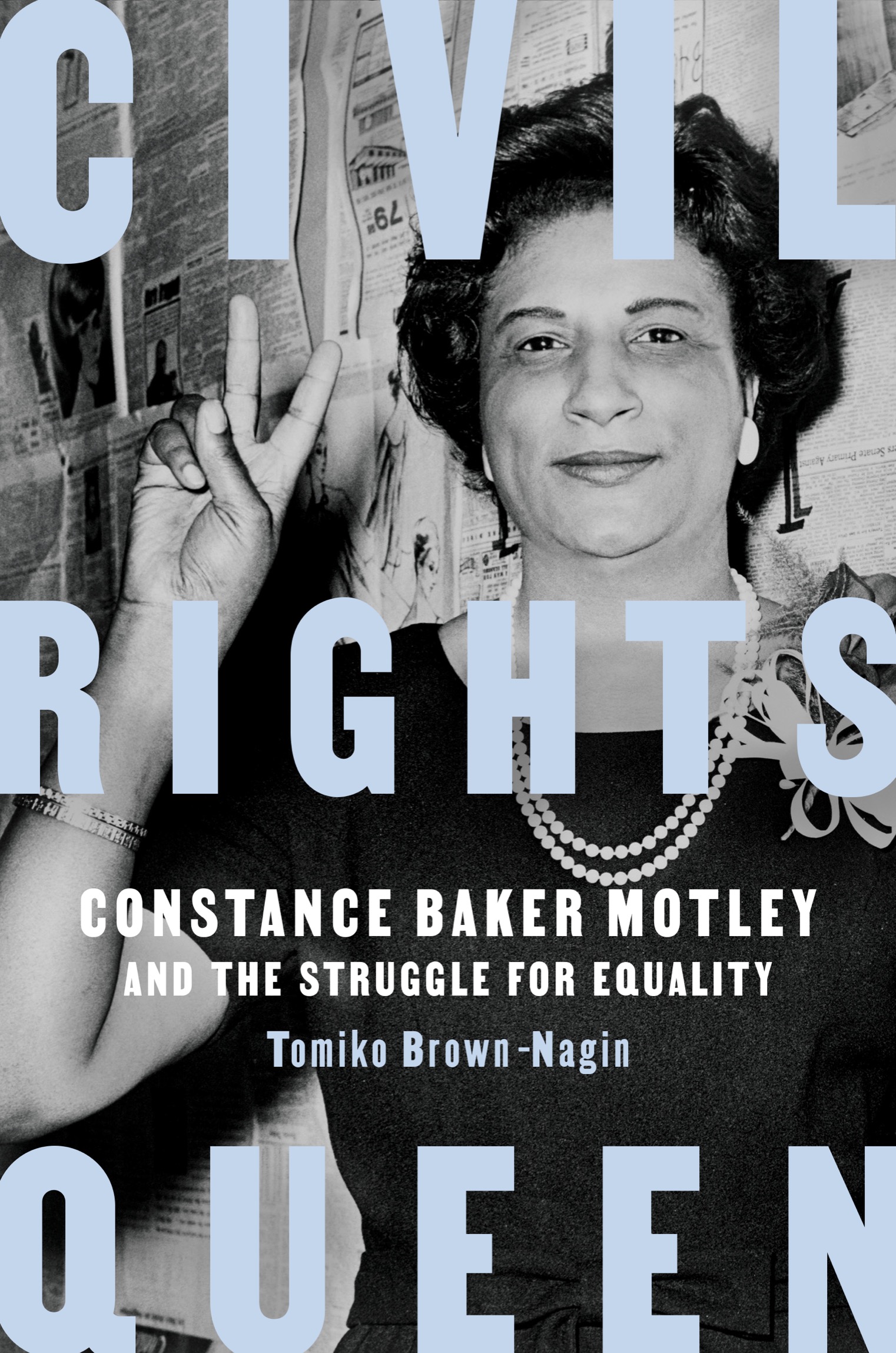

Compelling, candid, and highly revelatory. By examining in striking detail the remarkable life of Constance Baker Motleya formidable lawyer turned politician turned judgeTomiko Brown-Nagin makes a major contribution to several fields: race relations, womens studies, the study of the legal profession, and modern American history.

Randall Kennedy, Michael R. Klein Professor of Law, Harvard Law School

In Civil Rights Queen, award-winning historian Tomiko Brown-Nagin recognizes an unsung American heroine. Through an intimate, behind-the-scenes journey into what Motley did, where she came from, and how she got there, we learn the keys to Black womens successes in the twentieth century. A dazzling life story that inspires readers to discover the Constance Baker Motley in ourselves.

Martha S. Jones, author of Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All

Brown-Nagin brings a storytellers art, meticulous research, and astute legal and psychological insights to the life and times of a central figure of the civil rights movement. Readers will never forget the woman whose outspoken, proud, and ferocious sense of justice changed her fortunes while she challenged Americas racial apartheid, gender barriers, and day-to-day obstacles to human thriving.

Martha Minow, 300th Anniversary University Professor, Harvard University

An immersive and eye-opening biography. Brilliantly balancing the details of Motleys professional and personal life with lucid legal analysis, this riveting account shines a well-deservedand long overduespotlight on a remarkable trailblazer.

Publishers Weekly (starred review)

Also by Tomiko Brown-Nagin

Courage to Dissent: Atlanta and the Long History of the Civil Rights Movement

Copyright 2022 by Tomiko Brown-Nagin

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Pantheon Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

Pantheon Books and colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

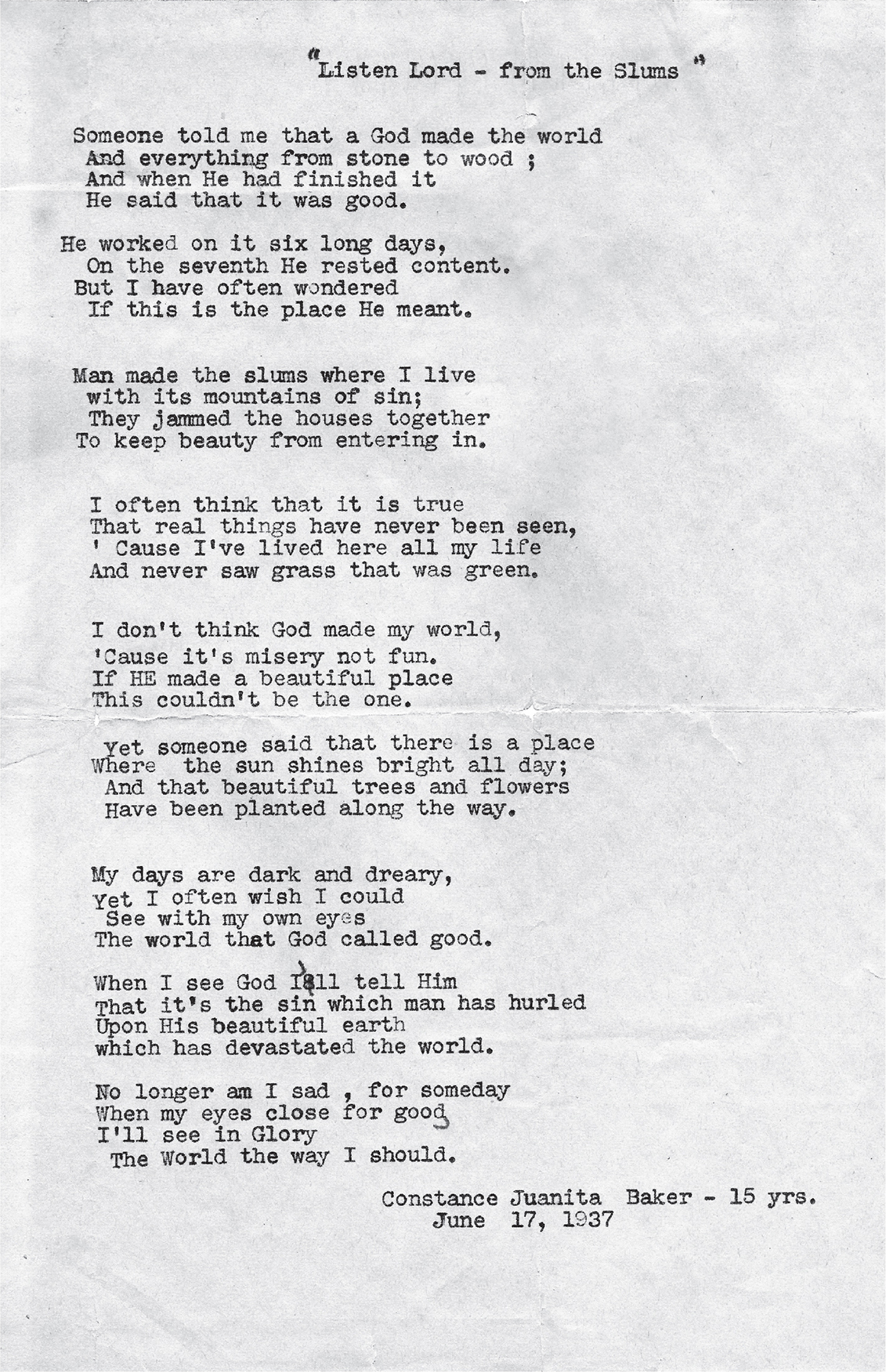

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the family of Constance Baker Motley for permission to reprint the poem Listen Lordfrom the Slums.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Name: Brown-Nagin, Tomiko, [date] author.

Title: Civil rights queen: Constance Baker Motley and the struggle for equality / Tomiko Brown-Nagin.

Description: New York: Pantheon Books, 2022. Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021022495 (print). LCCN 2021022496 (ebook). ISBN 9781524747183 (hardcover). ISBN 9781524747190 (ebook).

Subjects: LCSH: Motley, Constance Baker, 19212005. JudgesNew York (State)Biography. African American judgesNew York (State)Biography. Women judgesNew York (State)Biography. LawyersNew York (State)Biography. Civil rights workersNew York (State)Biography. Civil rightsUnited States. Equality before the lawUnited States.

Classification: LCC KF373.M64 B76 2022 (print) | LCC KF373.M64 (ebook) | DDC 347.747/0234 [B]dc23

LC record available at lccn.loc.gov/2021022495

LC ebook record available at lccn.loc.gov/2021022496

Ebook ISBN9781524747190

www.pantheonbooks.com

Cover photograph: Constance Baker Motley, February 6, 1964. World Telegram & Sun photo by Walter Albertin, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Cover design by Emily Mahon

a_prh_6.0_138967718_c0_r0

In loving memory of my mother,

Lillie Williams Brown

Contents

Introduction

Sam Terry was killed in cold blood. On February 27, 1949, a Sunday afternoon in rural Manchester, Georgia, about sixty-five miles south of Atlanta, white officers shot Terry a veteran of World War II, a member of the Greatest Generation, and a thirty-seven-year-old Black manthree times in the back, once in the side.

Terry had been arrested for a minor infraction that had nothing whatsoever to do with him. Two officers hauled him from his home and locked him in a jail cell. While he was detained, they unloaded their weapons on him, claiming he had resisted arrest and tried to break away from his cell. Terry died of his wounds two days later. In the aftermath, the local sheriff disclaimed all responsibility. His men had done nothing wrong, he said: no evidence was found that Terry had been mistreated by the arresting officersthe same men who shot and killed him.

Terrys widow, Minnie Kate, flatly contradicted the sheriff. Sam had not resisted arrest, his wife asserted; suffering from the mumps, he had been in no condition to attack anyone, much less officers of the law. But Sam had protestedverballywhen the officers had manhandled Minnie Kate and briefly placed her under arrest on trumped-up charges. Angered by Sams defense of his wife, the officers yelled, Shut up, you black son-of-a-bitch or well kill you. Once they arrived at the jail, the officers shoved Sam into a cell, followed him in, slammed the door, and immediately after fired several shots at him. Minnie Kate, standing just outside the cell door, witnessed the events unfold; what she had seen and heard was an entirely unjustified shooting a barbaric murder. What was more, Minnie Kate said, while Sam bled profusely from the gunshot wounds in his intestines, the officers had insisted that she had better not holler, or she would get the same thing.

News accounts and an attending doctor confirmed critical elements of Minnie Kate Terrys version of events. The Atlanta Constitution established that the doors of the cell had been locked when officers repeatedly shot Sam Terry. And the doctor who treated the veteran after the incident said that he had been shot four times. But Minnie Kate had no recourse in the state of Georgia, which at that time was governed by Herman Talmadge, a vicious racist. So she reached out to the national NAACP and its lawyers. Along with her allies, Minnie Kate urge[d] the lawyers to take action to see that this injustice is brought to the limelight and the guilty ones are punished. Murders of Black men are spreading throughout the Southland. She was not wrong. A reign of terror that began around 1880 continued through the mid-twentieth century: during this time, white mobs across the South, aided and abetted by law enforcement, murdered hundreds of African Americans, and often targeted Black veterans.

Terrys death came to the attention of Thurgood Marshall, the chief counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund (LDF, or Inc. Fund), and his legal assistant, Constance Baker Motley, then just three years out of law school. Springing into action, Motley wrote to Tom C. Clark, Attorney General of the United States, and requested a federal investigation. Marshall followed up with a letter to the Department of Justice, seeking the help of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Nothing happened.

In 1950more than a year after Minnie Kate Terry had buried her husbandMotley once again followed up with federal officials, to no avail. The Department of Justice closed the case, saying that the evidence was insufficient to support a prosecution. This failure to thoroughly investigate, much less prosecute, fit a pattern. Despite its wartime condemnation of the racism and violence of the Nazi regime, the U.S. government virtually ignored the wave of anti-Black terrorismthe all-too-frequent beatings, shootings, and lynchings of African Americansthat occurred in the postwar South. Veterans, who led a growing resistance to anti-Black oppression, were routinely victimized and in dire need of representation. Constance Baker Motley, then in her twenties, became one of the most prominent and tireless advocates for African Americans during this turbulent era.