Contents

List of Figures

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

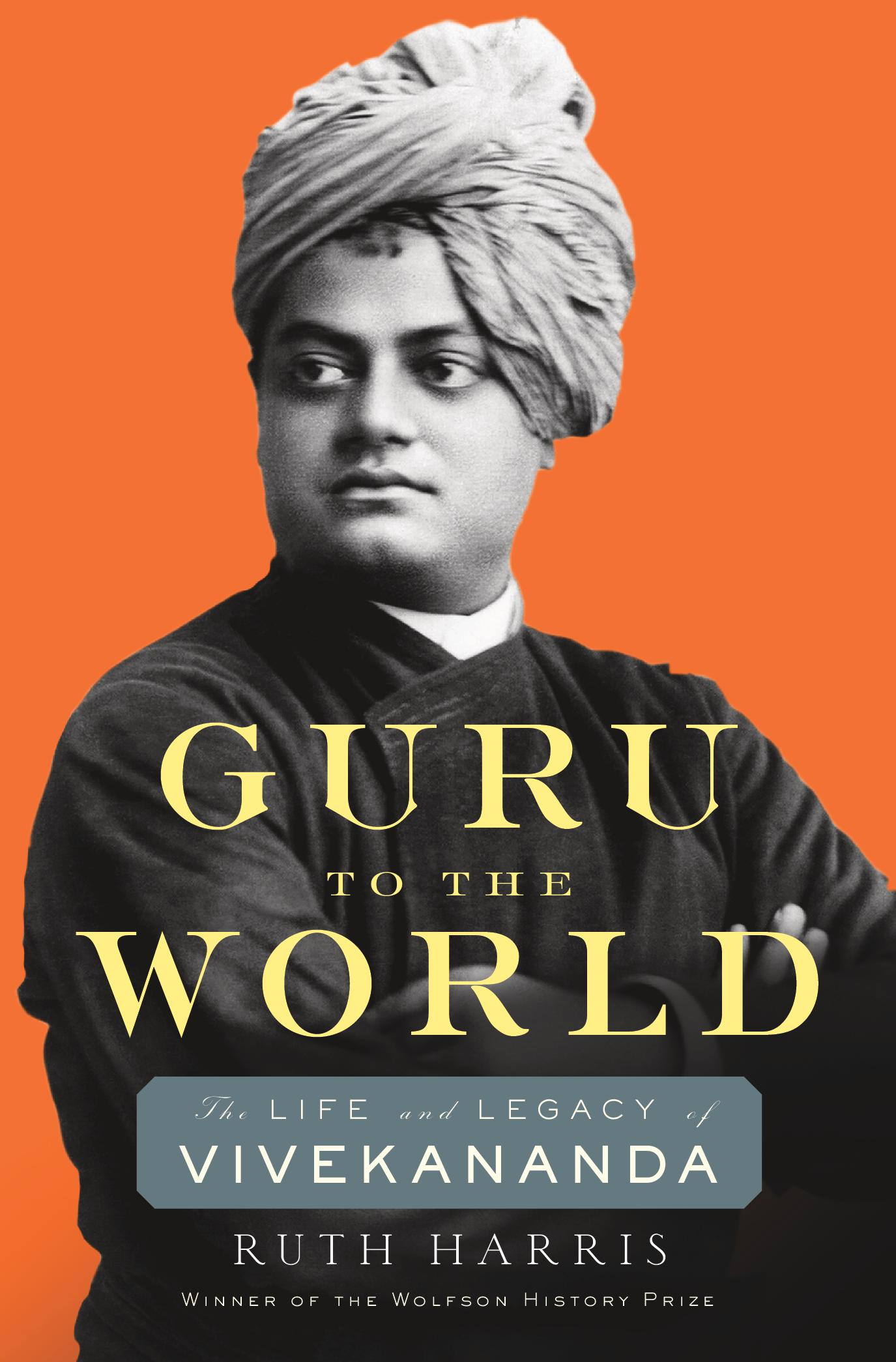

GURU

TO THE

WORLD

THE LIFE AND LEGACY OF

VIVEKANANDA

Ruth Harris

The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

2022

Copyright 2022 by Ruth Harris

All rights reserved

Cover image: Wikimedia Commons

Cover design: Marina Drukman

978-0-674-24747-5 (cloth)

978-0-674-28734-1 (EPUB)

978-0-674-28733-4 (PDF)

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Harris, Ruth, author.

Title: Guru to the world : the life and legacy of Vivekananda / Ruth Harris.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2022. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2022006018

Subjects: LCSH: Vivekananda, Swami, 18631902. | Vivekananda, Swami, 18631902Political and social views. | GurusIndiaHistory19th century. | Hindu philosophy. | Civilization, WesternHindu influences. | Hindu philosophersHistory19th century.

Classification: LCC BL1280.292.V58 H37 2022 | DDC 294.5/55092 dc23/eng20220525

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022006018

For Iain

Contents

Authors always like to construct retrospective accounts of why they chose their subjects and how they crafted their historical questions. Although such stories are generally too smooth to be truly believable, they reassure readers (and sometimes the author) that the book has direction and, hopefully, true purpose. In the past, I have felt that I had a clear and consistent understanding of my reasons for choosing a topic, and what themes and ideas I wanted to explore. But in the case of Guru to the World, I found that my relationship to both the work and its principal subjects shifted constantly and remained fluid till the end.

Perhaps I am simply more clear-eyed in accepting now that I have no straightforward tale to tell about the genesis of this book. This project surprised and dismayed both friends and colleagues who found it difficult to understand why I had chosen to leave behind three decades of work in French and European history to plunge into a study of Indian religion and the Atlantic world.

There are strands of continuity. I have always been fascinated by the fin de sicle and topics where science, religion, and healing mingle with politics and the lives of individuals. But I have never practiced meditation with any seriousness and have had no luck with yoga as a form of physical strengthening or spiritual advance. However, I did have very close American friends who had long abandoned conventional Jewish or Christian beliefs for yoga, mindfulness, and Hindu- and Buddhist-inspired ideas and practices, spiritual notions that were matched by a preoccupation with wellness and optimum health. I began to wonder how and why these womennearly always womencame to such ideas and what they meant in their lives. Their interest was all the more surprising given that only a few had ever been to India. This realization led to the question of how and why Westerners, and particularly Americans, could become interested in Eastern spirituality without having any deep matching interest in the East itself.

The intellectual / professional inspirations were not only more specific but also more far-reaching. Years ago, I wrote about the miracles and apparitions at Lourdes and investigated the religious experience of Bernadette Soubirous, whose visions of the Virgin occurred in 1857. After this study, I examined the life and work of Nobel Prizewinning intellectual Romain Rolland. Few realize that he spent a decade writing about both Ramakrishna and Vivekananda before introducing Gandhi to the French-speaking world. In reading Rollands study of Ramakrishna, I was struck by the parallels between the Indian mystic and Soubirous, the French saint. Not only was the moment of their first visions almost simultaneous; both Bernadette and Ramakrishna were illiterate, of poor background, and regarded as expressing some authentic, even primordial, truth about the divine beyond the grasp of the better educated. Moreover, their seemingly untainted religious experience inspired religious renewal in places where the local population felt downtrodden and immiserated. Both, too, were taken up by a cultivated audience.

Such links should not be overdrawn, but when I noticed the coincidences, they became crucial in prompting me to engage with global and transnational history, to look at parallel and virtually simultaneous happenings in new ways. My vantage point in Oxfordwhich has so many students from both India and Americawas a wonderful meeting ground for these two global cultures. Of course, my association with the United States was simple because of my American origins, even though I left my country long ago; encountering the depth and range of Indian scholarship was far less familiar and exhilarating. The realization of the often hidden impact of India on the West was enticing precisely because Eastern spirituality, yoga, and meditation became part of global culture at the very moment when Christian missionizing and Western imperialism were at their height.

After I encountered Vivekananda, the secondary question emerged of how a man who is a household name for millions of Indians around the world could be virtually unknown in the West, despite his enormous impact. I became even more aware of this discrepancy when speaking with Indian colleagues and friends who knew immense amounts about Spinoza, Mill, and Darwin while their associates in the West knew little of Indians, except perhaps Gandhi and Nehru, but certainly not Vivekananda.

My concerns at the beginning of this project lay mostly in exploring the reception of Indian ideas among alternative Western spiritual seekers. I soon realized, however, that this approach would once again prioritize the Western arena. For me, nothing was more humbling than my novice attempts at understanding Indian metaphysical thinking and historiography. I can only say that my colleagueshistorians of India in Europe and America and especially Indian colleagueswere astonishingly generous, tolerant, and helpful in steering me through the brambles and pitfalls while urging me onward.

Since then, I have begun to share my thoughts, and the process has been both warm and welcoming as well as bracing and questioning. Vivekananda has become highly controversial as a historical figure with a major contemporary political and religious presence in Indian politics. He remains an important figure in the inner lives of friends and colleagues who have both confirmed and challenged my conclusions when I have lectured or given papers. Responses from both sides have, I feel, strengthened my arguments, but I am aware that some readers will find my account too celebratory, and others will find it too critical.

Nonetheless, it has been a rare honorand the most invigorating intellectual experience of my lifeto have written a book that I hope will engage peoples emotions, intellects, and political sensibilities. All I can say is that I have striven to bring some balance to our historical understanding of global Vedanta and the extraordinary people who engaged in a rare, difficult, and sometimes confusing attempt to build bridges across cultural divides.

Indic languages include some letters with no equivalents in English. I have avoided the use of diacritics in this book because the general reader in India or anywhere else in the world is rarely helped by them and the scholarly expert will not require them. In addition, many place names and geographical landmarks, as well as orthographic conventions, have changed in the last few decades. Names of cities and towns, as anyone familiar with South Asia knows, continue to change. I have done my very best to standardize orthography and usage, and to make it as easy as possible for readers to locate the people and places in reference books and library catalogs.