Copyrighted Material

How Did I Do That?

A Life of Risk and Reward

Copyright 2021 by Bill Dutcher. All Rights Reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwisewithout prior written permission from the publisher, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review.

For information about this title or to order other books and/or electronic media, contact the publisher:

Wildcat Press, LLC

www.WildcatPress.partners

ISBNs:

978-1-7365826-0-2 (hardcover)

978-1-7365826-2-6 (Softcover)

978-1-7365826-1-9 (eBook)

Cover and Interior design: 1106 Design

To my lovely and loving granddaughters,

Hanna and Millie

INTRODUCTION

M y granddaughter Hanna was an aspiring ballerina at age three. Watching her practice at home one day, I saw her do a graceful pirouette, then exclaim in amazement: How did I do that?

Thats the same question I have asked myself, looking back, at age seventy-eight, on a life that has felt like a balancing act on a roller coaster. There are lots of books that prescribe a balanced life. This book shows what a balanced life looks like.

Like a mosaic, my book is composed of bits and pieces of memories dating back to the end of World War II. Each memory is associated with some heightened emotion, not just the thrill of victory and the agony of defeat experienced in sports and business, but also the love, laughter, joy, and pain shared with friends and family.

My mom once told me that when I was a baby, the Caney River flooded our hometown of Bartlesville, Oklahoma. When the high waters reached our home, she had to hand me off from our front porch to a man on a rowboat. This might have been an omen that I would lead an adventurous life.

From running my own neighborhood gang of Little Rascals to turning a journalism degree and a $500 investment into my own little oil-and-gas company, this book answers the question: How did I do that?

If life is a game, it is a game that can be won. As the famous television detective Monk would say when a case was solved: Heres what happened.

PART ONE

Glory days, well theyll pass you by

Glory days, in the wink of a young girls eye.

BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN

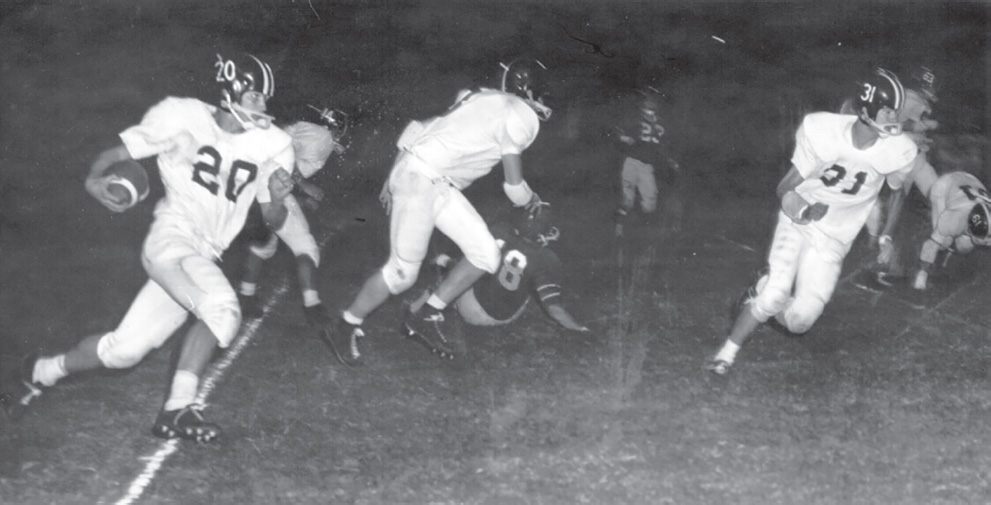

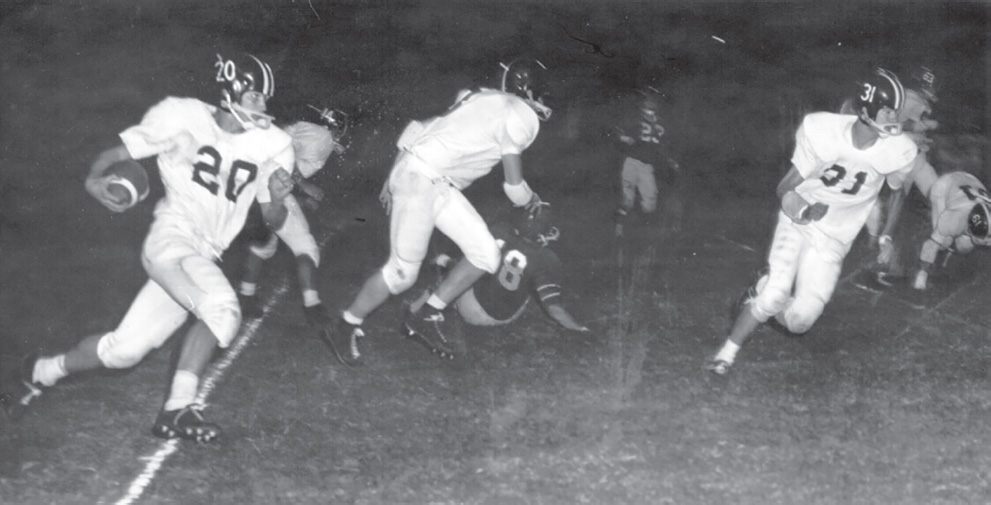

Mike Hewitt leads the way as I head for the end zone

CHAPTER ONE

A BARTLESVILLE

BOYHOOD

T he war is over! my dad called out to my mom as he bounded in the front door. I was playing with a toy truck in front of our living room fireplace. Dads news sounded important, and I made what must have been my earliest mental note. Assuming this was VJ Day, which marked the end of World War II on August 14, 1945, I was about two and a half years old. At that age, I liked to welcome Dad home by sitting on his good shoes, wrapping my arms around his calves, and holding on tight while he lugged me around the house for a while. He didnt seem to mind when I untied his shoelaces. He was probably ready to slip on his house shoes anyway.

My dad, Harris, my mom, Louise, and my brother, Del, older than me by three and a half years, made up my family. We lived in a small, white, one-story, two-bedroom, ranch-style home at 1515 Jennings, about a mile south of downtown Bartlesville, Oklahoma. My hometown had sprung up in January 1897 in what was then Indian Territory. Three months later, the Territorys first commercial oil well, the Nellie Johnstone No. 1, was drilled on the banks of the nearby Caney River, touching off an era of oil exploration and development in the area. Bartlesvilles population shot up from around seven hundred in 1900 to over six thousand in 1910, and the boom town eventually became the headquarters for two large oil companies, Phillips Petroleum Company and Cities Service.

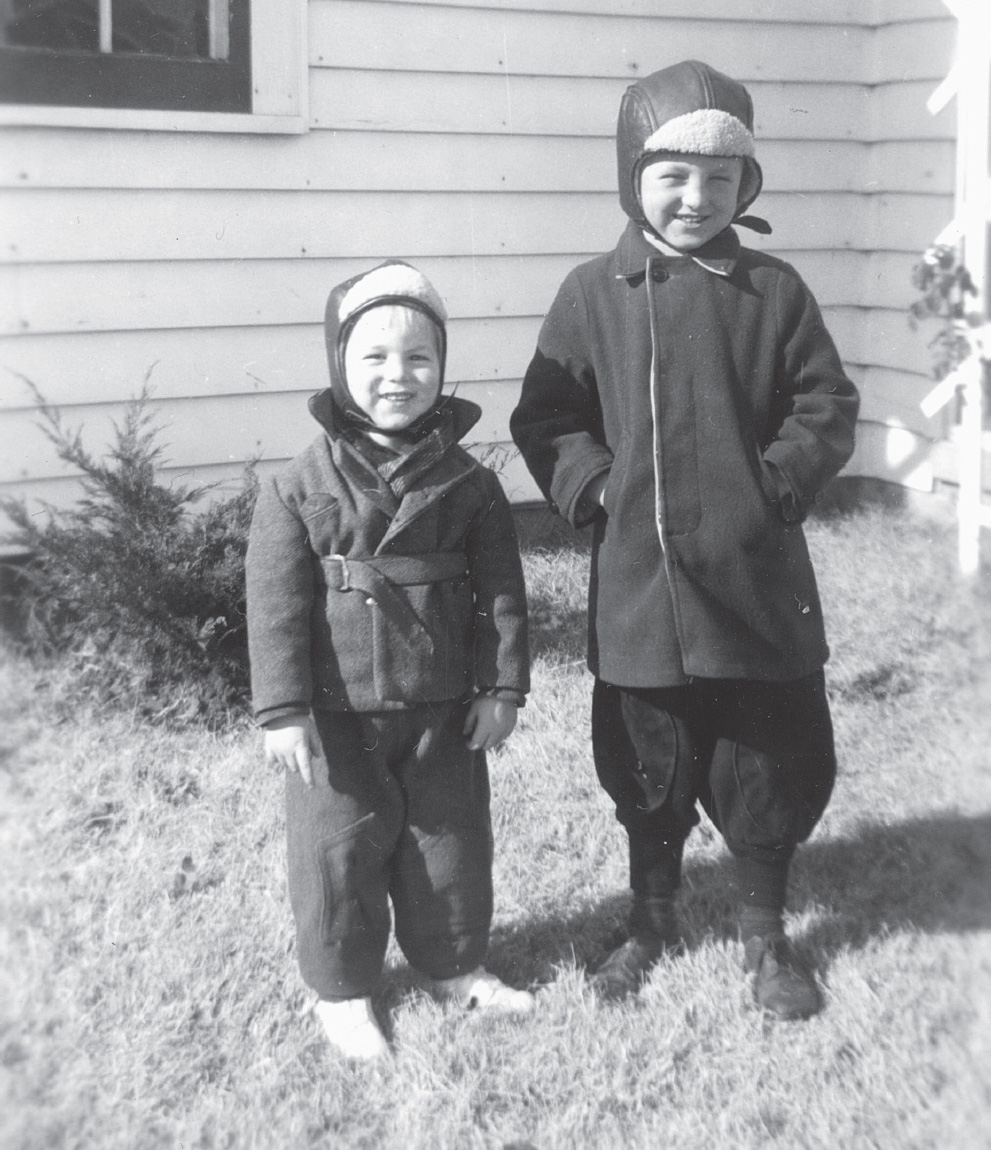

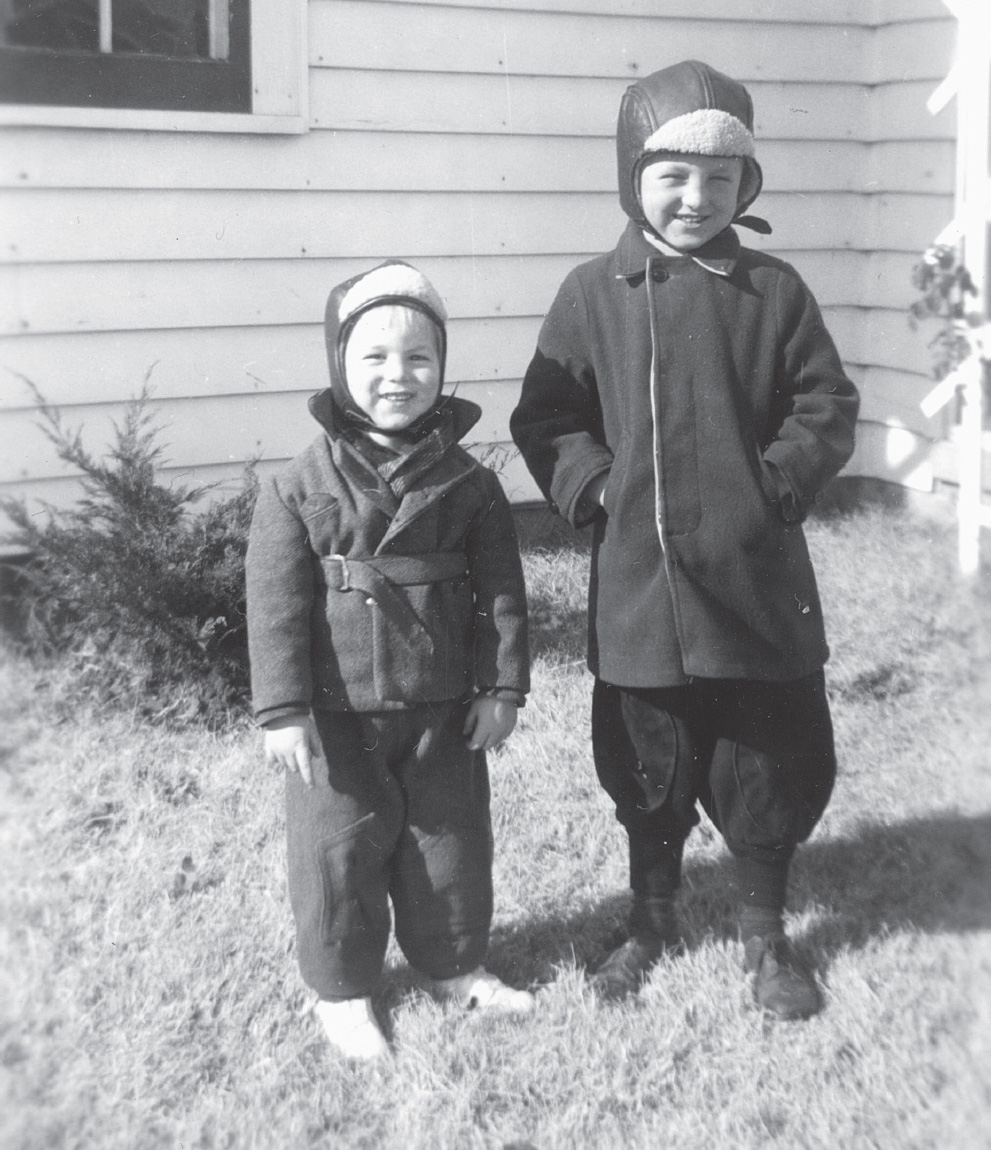

With big brother Del at home on Jennings Street

Dad was a chemist who worked in the research-and-development department at Phillips. He was also the first clarinetist in the Phillips company orchestra. Mom was an indifferent housewife and dedicated club woman. If Dad joined the Lions Club, she would join the Lion Tamers. When Dad was a Toastmaster, she was a Toastmistress. On Tuesdays, she would go to her Tuesday Club. Mom often mentioned she had worked as a legal secretary in Tulsa for a dollar a day during the Depression. But, in post-World War II Bartlesville, it was considered an admission of failure if a mans wife had to work outside the home.

My favorite early playmate was Dorothy Ann Bash, a girl my age who lived next door. She was a tomboy with long, black pigtails, always willing to go along with whatever mischief I could get us into. While I was a good boy who at times minded his mother, I often ignored her in search of adventure. Her default suggestion, Just go outside and play, was easy to comply with, and subject to a wide range of interpretation. Operating under the twin theories that what my parents didnt know would not hurt them, and that it is better to seek forgiveness than permission, I could always find something fun to do.

Mom often asked, Whats going on? If something was going on, she wanted to be part of it. I took her desire a step further. If nothing was going on, I wanted to make something happen.

Our gang, a real-life version of Hollywoods Little Rascals, included Teddy and Johnny, each a year younger than Dorothy Ann and me. We had the run of the neighborhood, but usually played within an area defined by Dorothy Anns house on the south, a row of six houses running north along Jennings Street, up to Teddys house. The houses had small backyards and a large, undeveloped field that separated them from the Santa Fe Railroad track, which ran through the west side of town. On many nights as a boy, the last thing I heard before falling asleep was the sound of a whistle as a train pulled into town and approached the Bartlesville station.

The Iceman Cometh

Lacking many of the modern appliances we now take for granted, we kept our food in a wooden icebox. An ice man would deliver a block of ice from time to time, just like the milk man, to a side door on our driveway. (To this day, I still call a refrigerator an icebox.)

In my pre-kindergarten days, there was a form of money in Oklahoma called mills. A mill was a small paper coin, worth one-tenth of a penny. But the big money was in pop bottles. Most soda pop was sold in glass bottles, and you could get a two-cent refund for each bottle returned to a store. Two cents would buy a piece of bubble gum. A Milky Way candy bar cost a nickel. An enterprising kid could buy a candy bar for two empty pop bottles and ten mills.

There was a little mom-and-pop grocery store on Armstrong, near the railroad tracks, a couple of blocks from our house. Our gang liked to take empty pop bottles to this store and cash them in for bubble gum or candy. One day I noticed that the store owner stored the bottles in crates behind the store. Sneaking behind the store, I took a couple of pop bottles, brought them back through the front door, and cashed them in for four pennies. Then I bought two pieces of bubble gum and walked out, my crime undetected. Either the store owner didnt realize the source of the pop bottles, or he just laughed and let it pass.