Copyright 2000, 2012 Sports Publishing Inc.

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Sports Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Sports Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Sports Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Sports Publishing is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.sportspubbooks.com

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file

ISBN: 978-1-61321-180-9

In memory of Dave Lidecka, one of the best sports editors around, and in thanks to Dennis Manoloff and my husband, Marc Halushka.

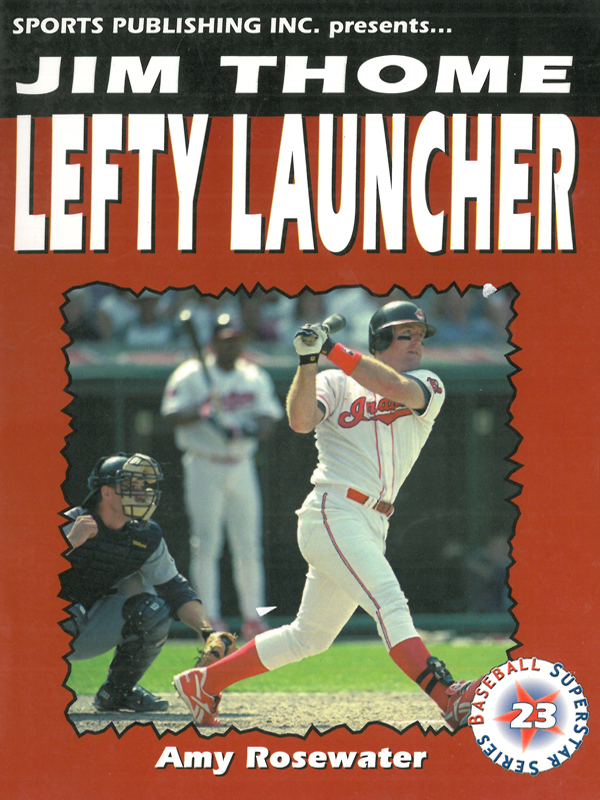

W hen Jim Thome turned 27, his Cleveland Indians teammates gave him a celebration he would never forget.

That night, August 27, 1997, the Indians played the Anaheim Angels. One by one, the Indians walked onto the field to their respective positions just as they always did. Jim, meanwhile, remained on the bench. A left-handed hitter, Jim sometimes would sit against left-handed pitchers.

As Jim looked out to the field from the dugout, he noticed something wasnt quite right. Everyone was at their usual positions: Omar Vizquel at shortstop, Matt Williams at third base and Sandy Alomar Jr. was crouched behind the plate. But they all looked a little bit different.

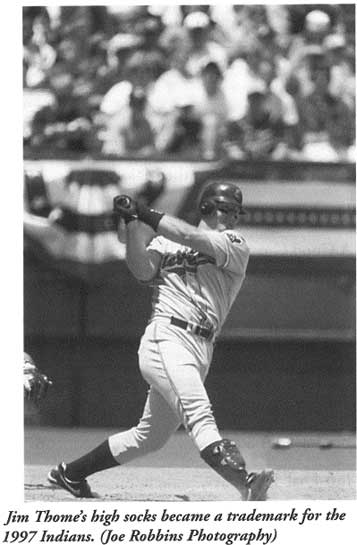

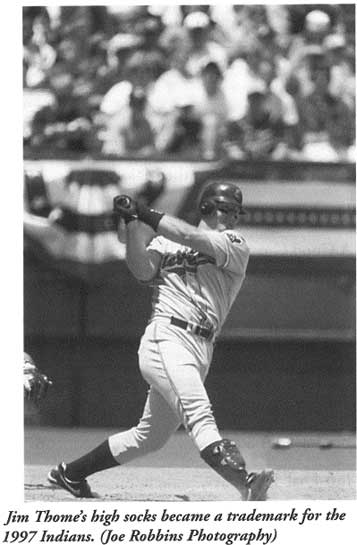

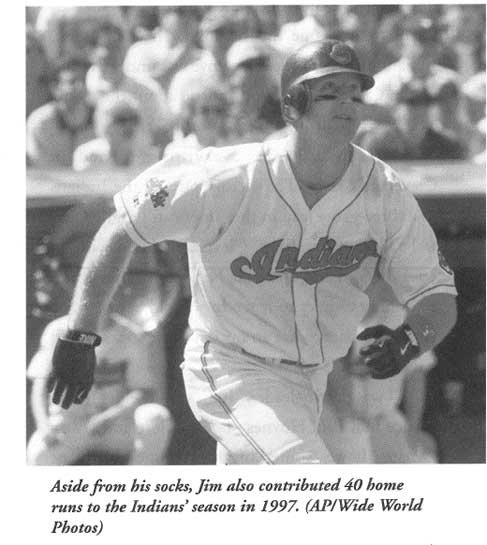

Virtually all of his teammates were dressed like him, with their red socks hiked up to the knees. On most days, Jim is the only member of the Indians who wears his socks knee-high in games. Jim began wearing them that way in the minors, as a tribute to old-time baseball and to his dad and grandfather, who also wore their socks high.

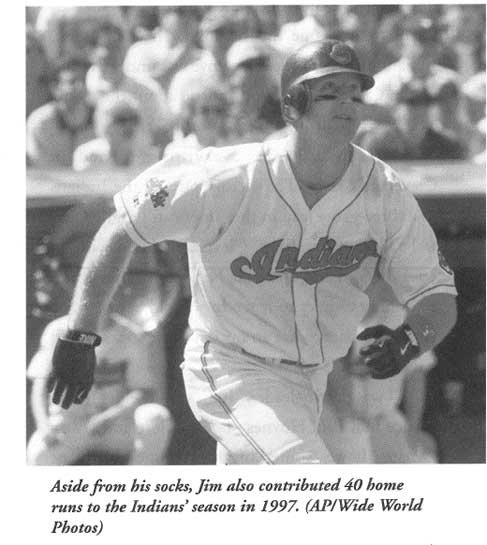

Now the tables had turned; his teammates were saluting him. Maybe those socks would help them hit 40 home runs, as Jim ultimately did that season.

They looked good, Jim said, smiling.

Jim approved of the way his teammates looked, but he liked the way they played even more. They hit like Jim that night, scoring 10 runs in the fourth inning against the Angels and winning, 10-4. Leading up to that game, the Indians had been in a funk. Indians manager Mike Hargrove was under fire and few in Cleveland were optimistic about the teams chances of returning to the World Series.

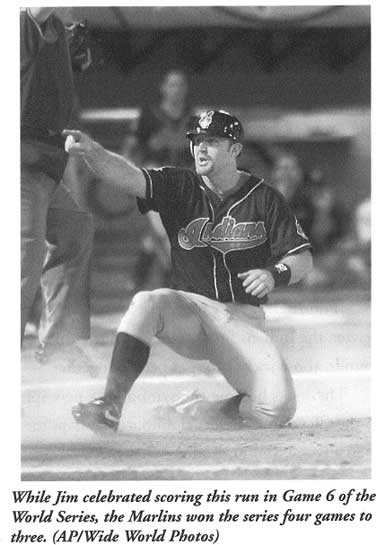

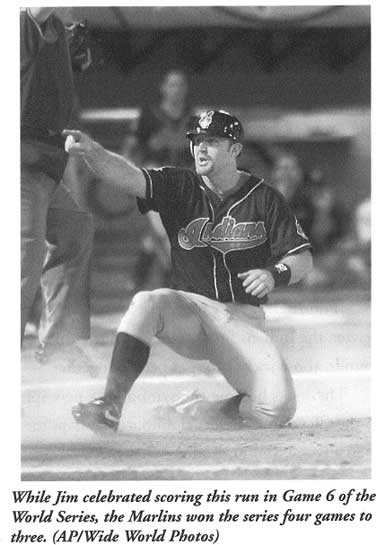

After that game, everything turned in Clevelands favor. The victory pushed the Indians to a three-game lead in the American League Central Division standings. Cleveland closed with an 18-14 record and upset the New York Yankees and Baltimore Orioles to reach the World Series.

Who knew what an impact those socks would have?

I was the ringleader, Indians outfielder David Justice told Paul Hoynes of The (Cleveland) Plain Dealer, It was something for Thomes birthday. Something for the team, something to show a little unity.

A one-day spoof turned into a season-long battle cry The next game, Hargrove and the coaching staff wore their socks high. When the Indians returned home for a three-game series against the Chicago Cubs, the grounds crew sported knee-high socks, too.

The fans also got into the act. Some wore buttons saying Socks Up and Get Knee High in Cleveland. It seemed everyone wanted to be like Jim.

I dont know why it took so long, said Kevin Seitzer, the Indians first baseman. But as silly as it sounds, those socks brought people together.

The socks became the symbol of a new spirit in the Cleveland Indians clubhouse. Perhaps more than anyone, Jim noticed the change.

To be honest, Jim said, I dont think we can say that all season long weve been having fun around here. But recently, its been different. Were having fun.

Jim never imagined he would be the teams fashion trend-setter. Nor did he expect his socks to be a reason why the team got out of its season-long funk and into the World Series.

It didnt matter to Jim that the team might have intended, at least initially, to poke a little fun at his socks. As long as the team was winning, Jim wouldnt care if they wore socks on their heads. In Jims mind, winning was the bottom line. After all, the Indians paid him to hit home runs and lead the team to championships, not for his good looks.

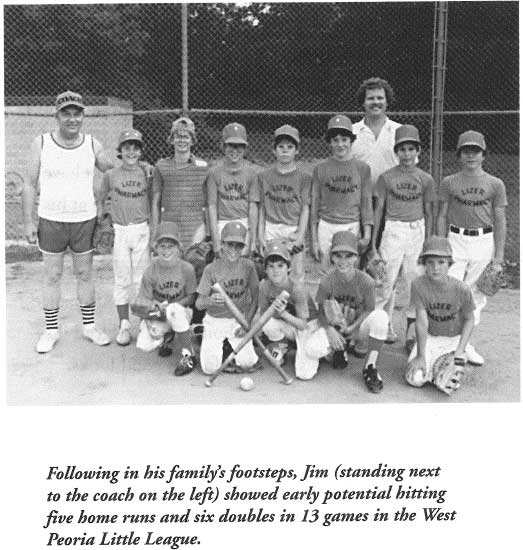

G rowing up in the heart of the Midwest in Peoria, Illinois, Jim was raised on sports. And baseball was at the base of his family tree. His father played fast-pitch softball. His grandfather played in the Three-I League, a minor league that had teams in Iowa, Indiana and Illinois. His aunt, Carolyn Thome Hart, is in the National Softball Hall of Fame.

Jims fondest memories were the trips he made with his dad to see the Chicago Cubs play in Wrigley Field. Peoria is a couple of hours southwest of Chicago, so driving to see the Cubs was always a special treat for Jim. He would see the Cubs play and dream of being a major-leaguer.

The youngest in a family of five children (twin sister, Jenny, is two minutes older than Jim), Jim grew up watching brothers Chuck and Randy excel in basketball and baseball. Jim didnt want to be as good as themhe wanted to be better. At the dinner table Jim would ask his mom how much milk his brothers drank when they were his age. Shed tell him, and hed respond by drinking even more. He wanted to be bigger and stronger.

Still, no one seemed to believe in Jim except himself.

I remember when he was little he said hed make it to the major leagues, said Jims mom, Joyce. He said, Im going to make it. Im not going to work.

He told us that forever, said Jims dad, Chuck. But it was all wishing and hoping.

Even though Jim was a standout player in high school, no major league teams drafted him. Undrafted but not undetermined, Jim continued to play baseball, hoping his dream would come true.

Jim decided to play at Illinois Central Junior College for a year so he could go through the draft again in 1989. No one paid much attention to him until he played in a junior college game in Chicago.