CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1

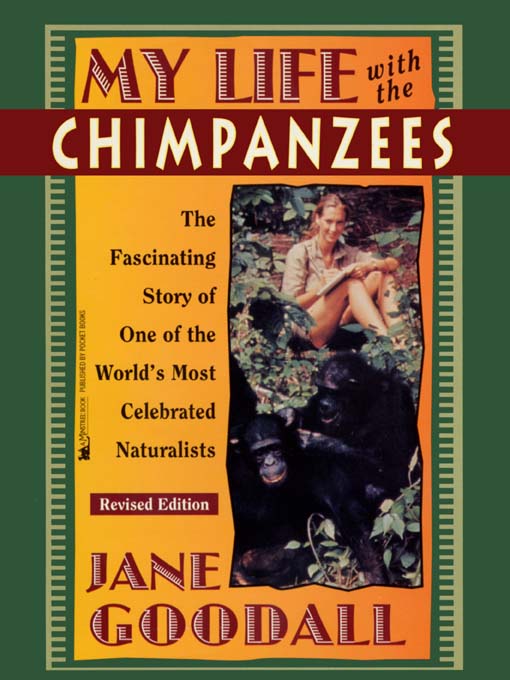

It was very stuffy and hot where I crouched, and the straw tickled my legs. There was hardly any light, either. But I could see the bird on her nest of straw. She was about five feet away from me, on the far side of the chicken house, and she had no idea I was there. If I moved I would spoil everything. So I stayed quite still. So did the chicken.

Presently, very slowly, she raised herself from the straw. She was facing away from me and bending forward. I saw a round white object gradually protruding from the feathers between her legs. It got bigger. Suddenly she gave a little wiggle andplop!it landed on the straw. I had actually watched the laying of an egg.

With loud, pleased clucks, the chicken shook her feathers, moved the egg with her beak, then proudly strutted her way out of the henhouse.

I tumbled out, stiff but excited, and ran all the way to the house. My mother was just about to call the police. She had been searching for me for hours. She had no idea that I had been crouched all that time in the henhouse.

This was my first serious observation of animal behavior. I was five years old. How lucky it was that I had an understanding mother! Instead of being angry because I had given her a scare, she wanted to know all about the wonderful thing I had just seen.

Even though I was so young at the time, I can still remember a lot about that experience. I remember being puzzled about eggs. Where on a chicken was there an opening big enough for an egg to come out? I dont know if I asked anyone. If I did, no one told me. I decided to find out for myself. I remember thinking as I watched a hen going into one of the henhouses, Ah, now Ill follow her and see what happens. And I remember how she rushed out, squawking in alarm, when I squeezed in after her. Obviously that was no good. I would have to get in first and wait until a hen decided to come in and lay her egg. That is why I was so long inside the henhouse. You have to be patient if you want to learn about animals.

When I grew up I became an ethologista long word that simply means a scientist who studies animal behavior. Most people, when they think of an animal, think of a creature with hair, such as a dog or cat, a rabbit or a mouse, a horse or a cow. In fact, the word animal includes all living creatures except for plants. Jellyfish and insects, frogs and lizards, fish and birds are all animals just as cats and dogs are. But cats and dogs and horses are mammals, a special kind of animal. Humans are mammals, too.

You probably know all that. Children today know a lot more about these sorts of things than most adults did when I was your age. I remember having a huge argument with one of my aunts when I tried to make her believe that a whale was a mammal, not a fish. She wouldnt believe me and I cried. I was so frustrated.

The first person to be known as an ethologist was an Austrian, Konrad Lorenz. He is often called the Father of Ethology. He has always loved animals of all kinds. In addition to the dogs he keeps as pets, he has lived with all kinds of wild animals in his home near Vienna. Most of these animals have been perfectly free to come and go as they please.

Konrad Lorenz is best known for his work with greylag geese. He began raising and studying them in 1935. He still sometimes observes them even now, though he is over eighty years old.

Konrad Lorenz found that adult male and female geese are very faithful to each other. They fall in love, marry, and stay together until one of them dies. Then the one who is left does not marry again. If its mother is still alive, it goes back to her.

Konrad Lorenz has been mother to many geesethose he raised from the time they left their eggs. When they became adult, these geese left him and flew off with wild geese. But if they lost their mates, they came back to Lorenz.

He found that baby geese, when they hatch from their eggs, learn to follow the first moving object they see. Usually this is the mother goose. But when Lorenz raised geese, they followed him, instead! Then he discovered that if he hatched mallard duck eggs, the ducklings refused to follow him. But if they were hatched by a domestic duck, they followed her at once. What did the domestic duck do that he, Lorenz, didnt? She quacked. And her quacking sounded just like the quacking of a mallard duck. Ah! thought Lorenz, that is the secret.

But scientists must always make tests. So, when the next lot of little ducklings hatched, Lorenz bent over them, quacked, and gradually moved away. They followed him! But it was very exhausting for him, taking his baby ducklings for a walk. If he stood up, towering high above them, or if he stopped quacking for more than a moment, they stopped following and began to cry loudly.

One day when Lorenz was walking the ducklings, something made him look up. Peering over the tall wall around the meadow were some of the village people. They were staring in horror at the professor who, as far as they could see, was quacking away to himself while creeping along the ground in a most peculiar way. The ducklings were completely hidden in the long grass! No wonder the local people began to think the professor was crazy!

Konrad Lorenz with his ducks. UPI/Bettmann Newsphotos.

Ethologists are interested in how animals live their lives and why they behave the way they do. They are always asking questions. Why does a dog go round and round in a circle before it lies on its bed? How does a male moth find his female even if she is miles away? And so on.

Some ethologists go on and on asking questions about one particular kind of animal. Karl von Frisch, a German, was fascinated by honey bees. How did a worker bee, returning to her hive after collecting honey, tell the other worker bees where to go? They could find her honey patch even if she, herself, didnt return. He found out that the returning bee performs a wonderful waggle dance that tells the others exactly where to go. She gives signals with her legs, her wings, and her tail. Then Frisch wanted to know whether she could see the beautiful colors of the flowers. How good was her sense of smell? The more answers he found, the more questions he asked.

Other ethologists are interested in a particular kind of behavior, such as the migration of birds. Or the different ways that juicy, nice-tasting insects mimic poisonous ones so they will not be eaten. Or the food-burying behavior of rats and mice. All ethologists ask questions. How? Why? What for?

Ethologists do their studying in different ways. Lorenz, as I said, took the animals he wanted to observe home with him. He had a very long-suffering wife!

Others, like Niko Tinbergen, another very famous early ethologist, do experiments out in the place where the animals live. Tinbergen is best known for his work with different kinds of sea gulls. He used to go out to the cliffs and rocky ledges where they breed. He spent a lot of time just watching them and writing down all the different things they did. But he also experimented. He learned some most extraordinary things. Some gulls, for example, become really excited if they see a giant egg. If Tinbergen placed such a monster near the nest of a herring gull or an oyster catcher, she would leave her own egg and desperately (and hopelessly) try to clamber onto the monstrous fake!