California Dreaming: The LA Pop Music Scene and the 60s

Guides to Music

Andrew Hickey

Published by Andrew Hickey, 2018.

For Holly

Copyright Andrew Hickey 2015, all rights reserved.

The author has asserted his moral rights.

All song lyrics are copyright their respective owners, and are quoted for review purposes in accordance with fair dealing and fair use laws. No claim over them is asserted.

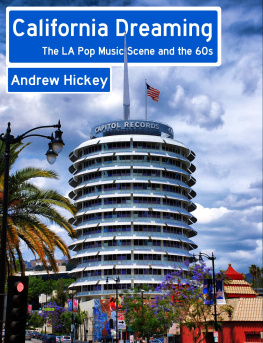

The cover image is based on a photo taken by Ryan Desiderio and licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License. Front cover design by Mapcase of Anaheim.

Moon Dawg

Nobody knows for sure who the Gamblers were the passage of time has added to the legend, and sources conflict as to who did what, but lets listen and try to hear who the players are at the start of our story.

It starts with the drums, of course.

Its a primal, rolling sound, one that has led many to say it must have come from the man who said let there be drums.

But while the legends that surround the session have everyone who is anyone there, to witness the pre-birth of a craze, it seems that Sandy Nelson was not the drummer. No, that sound is the sound of Rod Schaffer, a drummer who will pass out of our story very quickly, but who has as good a claim as any to have started it all. But hes playing in an imitation of the style of Nelson, who was the local boy made good.

Then the rhythm guitar enters, and from our lofty perspective more than fifty years in the future, were in familiar territory. This is surf music and, contra Hendrix, weve been hearing it again and again and again.

Except this is a year before surf music, before Dick Dale and His Del-Tones start playing music like this to surfers, gremmies and even the odd hodad, and before the sound of a reverbed Fender becomes synonymous with the waves.

This is, rather, the sound of Link Wray or Duane Eddy, as stripped down and reinvented by a gang of teenagers. Just hammer away at that single note as frantically as you can, dang-dang-dang-dang dang-dang-dang-dang. This is a young Elliot Ingber, who will go on to be a Mother before becoming Magic. Dang-dang-dang-dang dang-dang-dang-dang. Elliot has recorded this kind of thing before the Gamblers used to be called the Moon Dogs, and he had recorded Moon Dog with them but this is Moon Dawg

Then enter the bass just a low rumble here from Larry Taylor, no hint yet of the virtuoso who would play with everyone from the Monkees to Tom Waits, just holding the low end down, adding a bit of throb.

And then those staccato piano chords come in, and as they clang away we have to admit that here is where our stories start to conflict. Is this Howard Hirsch, the unknown keyboardist who played on the later Gamblers singles, or is it Bruce Johnston? Johnston was, after all, close friends with Sandy Nelson and Kim Fowley, both of whom are often credited here, but neither of whom had anything to do with it.

But despite that, my ears tell me its Johnston, and most of the sources I can find tend to agree. But maybe they, like me, are swayed by the incongruity of the man who wrote I Write the Songs hanging out with a bunch of reprobates like this, the kind of band whose B-side would be called LSD-25, in honour of a drug that the rest of rock music wouldnt start noticing for another seven years.

But no, its Johnston. Id recognise the sounds of the most clean-cut rock pianist this side of Neil Sedaka anywhere, doing his best Jerry Lee Lewis impression.

And if I had any doubts, theyd be swept away when those harmonies come in, with Johnstons voice to the front. Just a simple three-chord aah, block harmonies, following the rest of the track.

And forty seconds in we finally have the lead guitar, from Derry Weaver. This is the birth of surf guitar right here. Its not born fully-formed its a thin, wiry sound, without the reverb and distortion that would define the genre but the phrasing is all there. This is John the Baptist, paving the way for the Dick Dale that is to come. Derry Weaver was so lost to rock history that I have reference books good ones that say he never existed, but he was a real person, all right, a friend of Eddie Cochrane who Eddie had taught to play the blues.

And then the final element producer Nik Venet, howling at the moon.

This High Fidelity World Pacific Record, number X815, was only a hit in LA, but it didnt have to be a hit anywhere else. A year later, it was covered by a young garage band called the Beach Boys, who were produced by Venet (and who may have had some help on their cover from Weaver); their version is accidentally credited to Nik Venet rather than to Derry Weaver. And two years later, out in Cucamonga, in PAL Studios (the first independent recording studio on the West Coast), a cover version would be performed by the Hollywood Tornadoes. Their recording was engineered and produced by a young guitarist/producer/composer named Frank Zappa.

Everything this book is going to look at begins here, in this seemingly-unremarkable two minutes and sixteen seconds of vinyl and its B-side. The players we have assembled here will be, if not our principals, then the supporting artistes throughout this story, appearing again and again in various guises.

The surf music fad was only a short-lived one, and we will not be devoting much space to it in this book, but it was as important to the LA scene as the skiffle craze had been a few years earlier to Britain. It was primitive, but exciting, music that anyone could make. And soon anyone was. Well be looking at some of those who were in the next essay.

Heart and Soul

Jan Berry may not have been the most original musical force ever, but he definitely knew how to knock off someone elses sound successfully.

Hed been hanging around on the edge of the music business for years, first as a member of The Barons, a doo-wop group that got no further than playing a handful of high school hops, but which had featured Sandy Nelson on drums and Bruce Johnston on piano, and then from 1958 on as a duo with his schoolfriend Arnie Ginsberg.

Jan and Arnie had one massive hit, Jennie Lee, which had reached number three on the Cashbox chart. But the follow-up had only reached number eighty-one, the single after that hadnt charted at all, and Ginsberg had given up on the music business. Another former member of the Barons had just got out of the army, and so despite Dean Torrences manifest lack of singing ability, Jan and Arnie quickly became Jan and Dean.

But the new duo had an almost entirely parallel career trajectory to the old: a top ten hit with their first single, Baby Talk, and then a bunch of flops (with one fluke single just scraping the top forty).

They kept going for a few years, putting out singles with any label that would have them Dor, Ripple, Challenge with no success. These singles were nominally produced by two young men named Herb Alpert and Lou Adler, but Jan Berry was smart (he was studying at UCLA at the time, soon to transfer to the California College of Medicine to pursue a medical career in parallel with his musical one), and was watching and learning, as well as making sure that he got his fair share of the songwriting credit.

Theyd even managed to release an actual album, on Dor records, on the back of their one hit. The Jan & Dean Sound had a cover photo of the two crewcut teens wearing their best sweaters, and contained songs like White Tennis Sneakers and My Heart Sings. It didnt sell much, even by the small standards of the singles-dominated rock and roll market.

By April 1961 it had been almost two years since Baby Talk. Jan and Dean needed another hit. And so they got one by Jans favourite technique copying someone else.