Wakefield Press

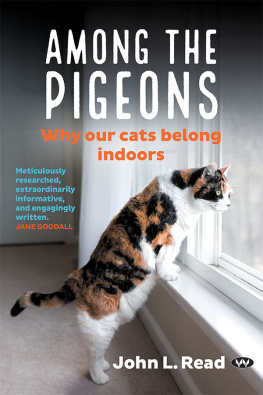

John Read is an ecologist and author, passionate about informed and pragmatic approaches to environmental and animal welfare issues. His ecological research has featured in over 120 scientific articles and he sits on a range of scientific advisory groups. He has also published three acclaimed books on topics as diverse as desert ecology, saving an indigenously owned tropical rainforest and cross-cultural attitudes to war. John lives on South Australias largest privately managed nature reserve with his wife, children and endangered malleefowl and marsupials.

www.johnlread.com

Wakefield Press

16 Rose Street

Mile End

South Australia 5031

www.wakefieldpress.com.au

First published 2019

This edition published 2020

Copyright John L. Read, 2019. All rights reserved. This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced without written permission. Enquiries should be addressed to the publisher.

Cover designed by Liz Nicholson, Wakefield Press

Edited by Julia Beaven, Wakefield Press

ISBN 978 1 74305 726 1

Set the cat among the pigeonsto cause trouble

Contents

No other animal in the history of man has experienced such vagaries of fortune as the cat.Eugenia Natoli

Connection with nature grants us automatic inclusion into a worldwide fraternity of diverse yet kindred spirits. The pitiful round eyes of orphaned orangutans in a clear-felled rainforest inspire universal empathy. Paradoxically, many an ornithologist entered their vocation through collecting rare bird eggs, while expert hunters often become the most astute and dedicated wardens.

But our views on cats often represent a striking aberration. More so than any other animal on the planet (with the possible exception of snakes and sharks) cats divide opinions. Any group of compassionate animal lovers is likely to harbour diametrically opposite views on the rights or impacts of free-ranging domestic cats. Let me demonstrate.

Outside, right now, an unknown cat meows at your door. What do you do? Offer it a bowl of milk or hurl your boot at it?

Presumably the extremists, anyone either predisposed to torture the cat or unconditionally invite it inside, would not have read this far into the book. But for the rest of us, this desperate cat represents a conundrum. Could it be the ultimate companion animal, both vulnerable and affectionate? Its not the cats fault it is hungry and unloved. This cat, or its mother or grandmother, was probably allowed to roam by an irresponsible owner.

Cats, particularly kittens, exemplify characteristics that endear vulnerable animals to caring humans. Their large eyes, baby-like crying and inherent vulnerability tug at our heartstrings. Kittens inspire many of us to take pity or show affection in ways a beady-eyed rodent or impassionate reptile do not. Anthropologist Peter McAllister has categorised the ability of cats to trigger parenting responses in humans as a form of brood parasitism, analogous to cuckoo chicks deceiving their hosts to feed them. Like it or not, we are instinctively programmed, and sometimes even hormonally hardwired, to care for cats.

But hang on. Back to that cat outside the door. Maybe its the infuriating culprit that uses your sandpit as a toilet, exposing your kids to insidious diseases that may come back to haunt them decades later. Or the raider of the bird nest your family had been carefully watching for a month until an empty nest and tatty feathers dashed your hopes. Or the stray tom that beat up your adored pet cat.

Some of us sympathise with the outspoken proponents of Trap-Neuter-Release (TNR), those who vehemently oppose euthanasia of any unowned cats. Others side with the more discreet, self-confessed practitioners of SSS; or Shoot, Shovel and Shut-up.

Intriguing and divisive, alluring yet despised, cats fire our emotions and can distort our perceptions. How cats have managed to walk this tightrope of human affection and disdain for so long remains a perplexing question for animal lovers and social commentators.

The most common and widespread pets in the world, domestic cats are among the first animals seen by infants and the primary pet of choice for many elderly. Cats are welcomed into our homes and farms and typically tolerated in our villages and cities. The number of pet cats continues to increase in all corners of the globe, exceeding dog ownership in many countries including the United States, United Kingdom and China. In concert with bourgeoning human populations, the number of pet cats sped past the 200 million mark in 2005 and shows little sign of abating. Pet cat numbers in the USA have tripled since 1970, with 15 million additional cats added each decade. From Manhattan high-rise apartments to remote villages in Papua New Guinea, more cats are invited into our lives than ever before. Cats are truly ubiquitous and remarkable, adaptable and fascinating. And their besotted owners surely rank among the most tolerant and obsessed of pet keepers.

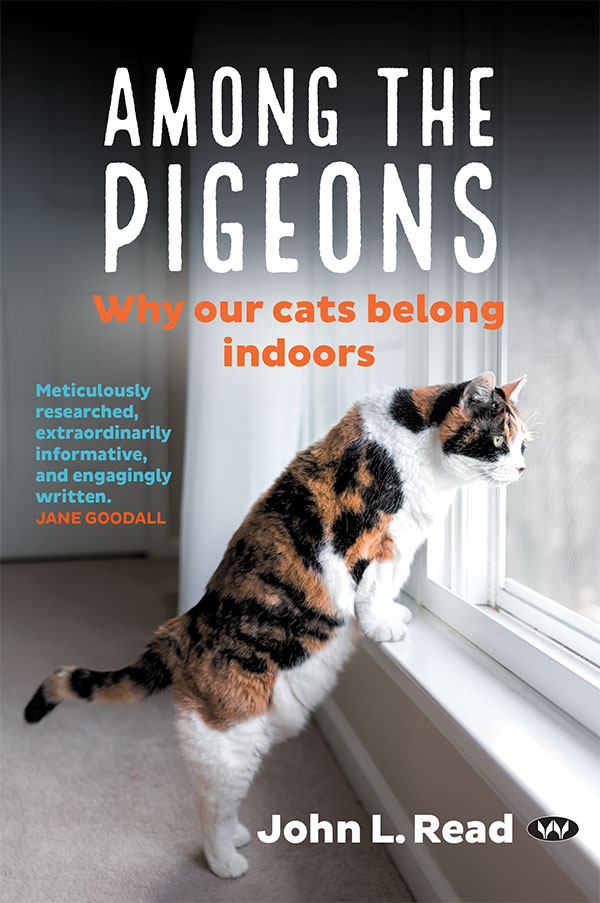

The domestic cat has been living in close association with humans for at least 3500 years and maybe twice as long, since their domestication from the African wildcat. Ironically, despite their somewhat misleading common name, domestic cats have only ever been partially domesticated. The plethora of specialised dog breeds, from Great Danes to lapdogs, is testament to the ability of dog owners and breeders to segregate and determine the mating options of their pets. By contrast, the vast majority of pet cats belong to a homogenous cosmopolitan gene pool. Litters are typically sired by multiple toms, sought out by oestrous females, not their owners. Even when deliberately kept indoors and typically reluctant to venture outside, a queen cat on heat becomes single-minded and elusive. Their determined reluctance to acquiesce to the desires of their would-be masters epitomises the characteristics that make cats both intriguing and frustrating.

Georges Cuvier was the pioneering biologist who first recognised that extinction occurred and hence paved the way for the Theory of Evolution. Ironically, Cuvier flatly refused to believe species could change through time. His evidence was that cats had been intransigent; there was no significant difference between fossils of several thousand years ago and recent cat skeletons. Marion C. Garretty summed up Cuviers belief when she observed: Humans remade dogs to suit their own ends. Cats are exactly the same as they were 10,000 years ago.

The Egyptians, who first domesticated cats from their wild northern African ancestors, held them in such high esteem their deaths were mourned like beloved family members, complete with embalming and burial in mass cemeteries. In what must surely rank as the most bizarre mineral deposits ever commercially mined, a staggering 19 tons of mummified cat bones, calculated to have originated from 80,000 pet cats, was shipped from Beni Hasan on the banks of the Nile to England in the late 19th century to make fertiliser. However, despite their obvious abundance and widespread appeal, domestic cats were very rarely seen in Europe until 300 AD. But once there the cat was, quite literally, out of the bag. The medieval king of Wales, Hywel Dda (the Good), was so enamoured by cats he passed the first animal welfare law in the world by making it illegal to harm a cat. To this day, cats are afforded more free licence than any other pet. Australias peak animal welfare organisation, the RSPCA, acknowledge that Cats are some 30 years behind dogs in terms of legislation and some 300 years behind in terms of pedigree breeding.