GO ASK YOUR FATHER

One Mans Obsession with Finding His OriginsThrough DNA Testing

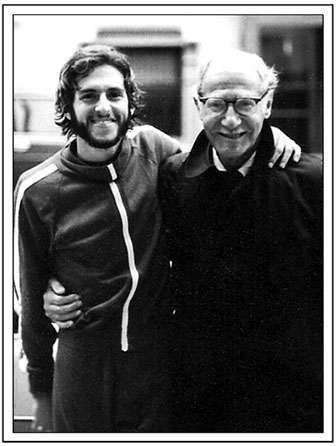

Lennard J. Davis

Also by Lennard J. Davis

MY SENSE OF SILENCE: MEMOIRS OF A CHILDHOODWITH DEAFNESS

THE SONNETS: A NOVEL

SHALL I SAY A KISS? THE COURTSHIP LETTERS OFA DEAF COUPLE, 19361938

OBSESSION: A HISTORY

Smashwords Edition

All rights reserved.

Copyright 2009, 2015 by Lennard J.Davis

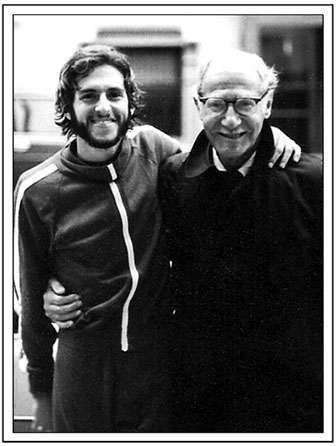

Photograph on page 164 by Henry J. Mueller.All other photographs courtesy of the author.

Previously published in paperback by

Bantam Dell

A Division of Random House, Inc.

To my wife, whose love helps me understandtruly who I am

Table of Contents

There was a man dining with us one day whohad had

far too much wine and shouted at mehalf-drunk and shoutingthat I was not rightly called my fathers son .

SOPHOCLES,

OEDIPUS TYRANNUS

Prologue: Little Oedipus

It is agrim Saturday morning in the Bronx in 1957. The wind whistlesoutside the windows of a dingy synagogue as I peer through thesmudged stained-glass window of the small room adjacent to the mainhall. Ive chosen to see the world through the cobalt-blue pane, myfavorite hue. Amethyst trees strain against the force of the royalblue wind while indigo birds wheel in the sky. Inside the shul, the men are chanting in theirlugubrious voices the Hebrew prayers, which undulate in minor keys,praising the power of Yahweh. The women, behind a curtain on theside of the room, sing their plaintive counterpoint.

Those ofus with living parents have been called into the small anteroom sothat those with dead parents can recite the Kaddish, the prayer for the departed, in unison. Therecently bereaved and those celebrating the anniversary of thedeath intone: Yeetgadal v yeetkadash shmey rabbah, followed by the Eastern European Ormain! for Amen. Nothing soundssadder than that prayer. I dont question the wisdom of thistradition, but I am thankful that my mother and father are aliveand padding around our onebedroom apartment a few blocks away. Ivecome on Saturday morning all by myself to attend the Sabbathservices. Ive just turned eight and am feeling quite worldly in myindependence, and very religious, sanctified, and holy. During thereading of the Torah, we young ones will be taken upstairs to theeven dingier Dickensian halls of the Talmud Torah school, where wewill be told Bible stories, allowed to play games such as Steal theKosher Bacon, and be given at last the Nestls chocolate bars thatI love and craveprobably the ultimate reason I like going toSabbath services.

Suddenly, a boy claps his hand on myshoulder. He is a year or two older. There is a strangely dementedlook in his eyes. For no apparent reason, except for the joy ofspreading information or perhaps of trumping a younger boy withastounding news, he quizzes sotto voce: Hey, know what yourparents did to get you born?

Sure, I say, not really knowing.What?

I...I...

He doesnt wait. He cant wait, really.Your father put his dick in your mother.

This is a little confusing since he doesntseem to have completed the sentence. Into my mother? I know what adick is, and the idea that my father put his dick into my mother isinstantly unappealing. I had used my dick for something calledpee-pee, and not much else. The idea of me, for example, puttingmy dick in Jill Schwartz, my upstairs neighbor, seemed not onlyrude but also unpleasant. And where would I put it into her? Thatraised other unseemly questions.

So Irespond categorically, My father did not put his dick into mymother. My father was British and so was my mother. They were veryproper and never even used dick. They used wee-wee to meand penis when theyhad to, both of which were the more polite words said by the bettersort of people. I was sure that if the president ever said anythingabout his dick, in the privacy of his own home, to his mother, hewould have used wee-wee, as Idid.

But the boy insists, now with glee. I canhear the old men and women chanting for their dead parents. Didthose revered and departed men and women condone the fact thatJewish mens dicks, rabbis dicks, were put into Jewish women,rabbis wives? I strongly doubt it. Jewish history and cultureseemed opposed to that idea. For one thing, it wouldnt have beenkosher, I feel sure.

I say with a clear finality, My fathernever put his dick into my mother to have me.

The boy laughs. Youll see. Youlllearn.

I dont want to believe this. The boy iswrong. The azure wind blowing through the amethyst trees knows thathe is wrong. The world glimpsed through my cobalt-colored stainedglass knows he is wrong. My teachers at public school would back meup.

As the prayer for the dead ends, we areushered back into the main hall. The deceased have been mourned;parenthood has been uplifted; all is well. Now it is time to singmore prayers in anticipation of the chocolate bar awaiting usupstairs.

But that problem did my father put his dickinto my mother to have me?would, strangely enough, resurface manyyears later, not in the way the boy meant but in a much moreprofound way. Eventually I did of course learn about sex, about thebirds and the bees, but, like Oedipus, I still had much more tolearn about myself and the truth of my origins.

ONE

A Phone Call and Its Consequences

It was June 2, 1981, and I was in myapartment on Morningside Drive in New York City working on a newbook. A professor in the Columbia University Department of English,married, with a oneyear-old son, I had a life that seemed prettysteady. At that particular moment, however, I was grieving. Myfather, Morris Davis, had died a week earlier, just before hiseighty-third birthday, after a long, slow decline caused byprostate cancer.

Born in 1949, I was the son of Morris andEva, and I had grown up in the Bronx with my brother, Gerald. Asidefrom the fact that my parents were both deaf and we spoke signlanguage at home, ours was a typical, ordinary family. I felt surethat I understood the basic contours of my life as well as anyoneelse did.

But this was a difficult time. I was stillfeeling the strangeness of being an orphan. My mother had died tenyears before, having been hit by a truck while crossing the streetwhen I was twenty-two years old. And now my father, too, was dead,a mere two days after slipping into a coma.

The phone rang, taking me away from my work.It was a call from my uncle Abie, my fathers younger brother. Webegan talking about dividing up some of my fathers possessions. Aswe were discussing these details, I remembered that a month or twoearlier Abie had taken me aside at my fathers hospital bed andsaid in an unwelcome, confidential tone, Ive got a secret, but Icant say what it is until your father dies.

At the time I had shrugged off Abiessepulchral whisper in my ear as yet another of the odd and annoyingthings that had come out of his mouth over the years. Abie wassomeone my father and mother had held in low esteem. Whenever theytalked about him, they presented him as an example of what not tobe like: he was always late and always impulsive, and he did thingsthat I was told not to do. These were rather ordinary things that,I learned later in life, many people didthings such as read inbed, read on the toilet, and hang around the house in his pajamasall morning. But there was a particular urgency in the way I wasencouraged not to do such things. My father, Morris, was a precise,orderly man of British birth who prided himself on punctuality andcontrol. He was a man who went to sleep when his head hit thepillow, emptied his bowels on schedule and without the aid ofprinted matter, arrived on time, and got up in the morning dressedfor action. Abie was his opposite, his less superego-drivencounterpart. In addition, having lost one wife when he was youngerand divorced another in later years, Abie had dated a constantlychanging stream of women even into his seventiesin sharp contrastto my fathers lifelong history of steady and devoted monogamy. Inour family, Abie was what one should not be. Not exactly a rebel,but someone without a cause.