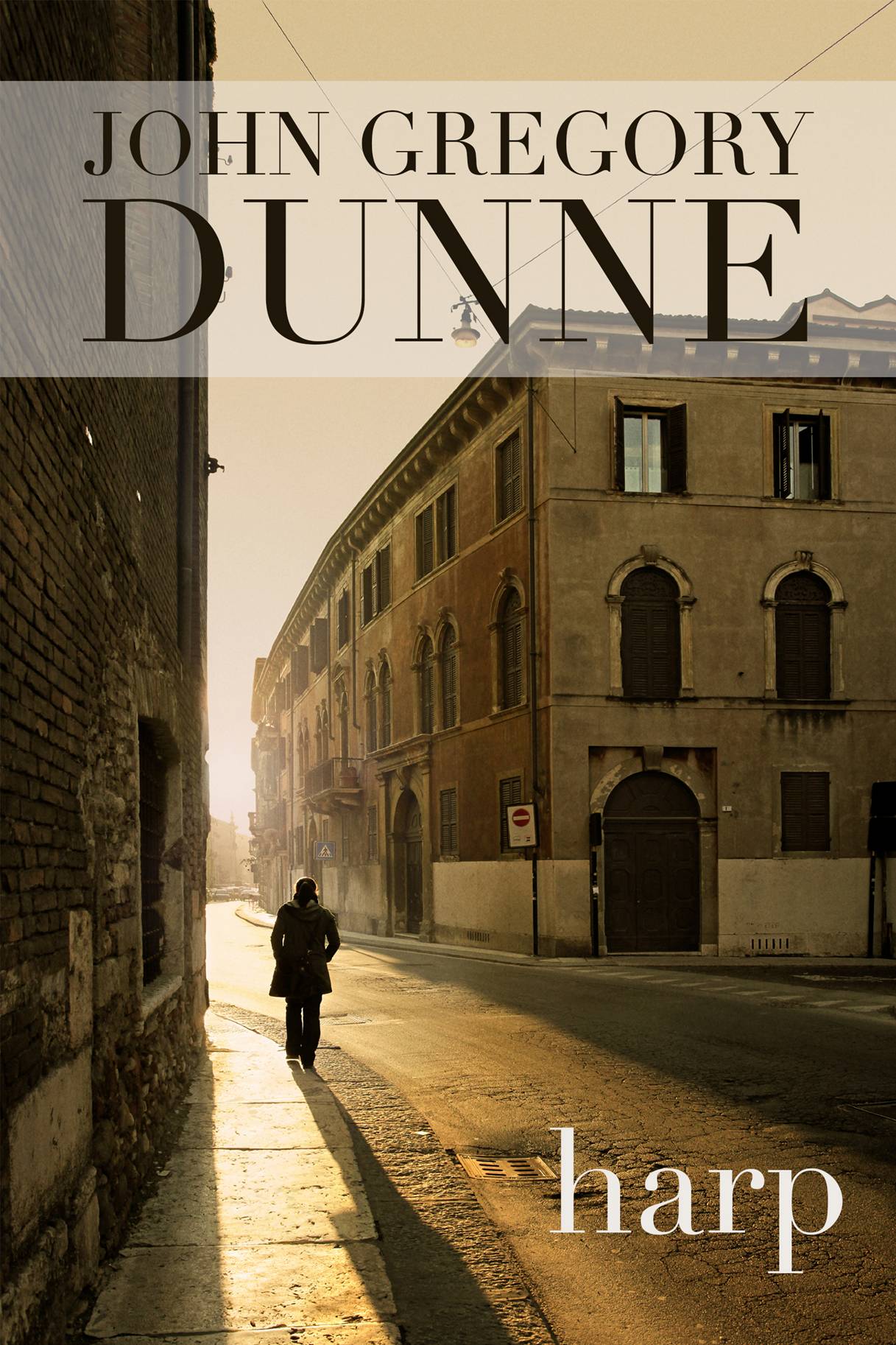

John

Gregory

Dunne

Harp

This book is for my friend Tony Richardson

It is for my friends Alan and Marilyn Bergman

And finally it is for dearest of the dear Laure Dunne

And her sons Harrison, Justin and Evan

Try to be one of the people on whom

nothing is lost.

- Henry James

When Irish eyes are smiling

Sure its like a morn in spring.

In the lilt of Irish laughter

You can hear the angels sing...

- Old Irish Lie

I was not given to personal reflection, had always looked unkindly, in fact, on introspection. Then in the seventh year of the Reagan kakistocracy, the medical dyes shooting through my arterial freeways were forced to make a detour around a major obstruction:

PART ONE

I

There is no good that can come from a telephone call at 4:30 in the morning. The best you can hope for is a wrong number, a drunken friend, a hang-up. I looked at the luminous bright blue figures on the digital clock radio and I hoped it was a dream and I hoped the ringing would stop and when it didnt I ran over the possibilities as I reached, still drugged with sleep, for the receivermy daughter, on a school camping trip to Yosemite (sweet Jesus! the thought nearly stayed my hand), my aunt, the last family survivor of her generation, vital, exasperating, still a force, but after all eighty-three years old. Not Stephen, never Stephen, Stephen in the white sailor suit, Stephen with hair the color of sunlight, Stephen the baby of the family, Stephen my brother, Stephen the husband and father, Stephen the graphics designer, Stephen who had the gift of laughter, Stephen, at forty-three, dead of his own hand, a suicide.

It is an imposition on the reader to write that paragraph, but there are those of us for whom words have no meaning until they are down on paper. Clarity only comes when pen is in hand, or at the typewriter or the word processor, clarity about what we feel and what we think, how we love and how we mourn; the words on the page constitute the benediction, the declaration, the confession of the emotionally inarticulate. I do not wish to eulogize Stephen; he was far too private, and even the wish would embarrass him. Nor will I try to understand him; it is hubris of an almost obscene dimension to pretend that one person can ever truly understand another.

I only wish to remember him. I sit in an office surrounded by fragments of his life and mine, old photographs taken in houses I no longer remember, crumbling newspaper clippings of graduations and engagements and weddings, scribbled notes with references to people only dimly recalled, pictures of aunts and uncles and second cousins of another generation, mass cards printed for the funerals of each of our parents, snapshots of old girlfriends of his and a former fianc of mine, a proposal for a graphics design corporation that Stephen planned to start and I invest in, Christmas cards from Stephen and Laure with first one son and then a second and then a third. Each memento is a shard of memory, a tile in a mosaic that reveals all and tells nothing. There is Stephen in a playpen and there I am in what appears to be a Royal Canadian Mountie costume: was it Stephen who called me Sheriff? It had the touch of his irony.

Our father was a surgeon, our mother a housewife; my fathers parents died before I was born, and I can never remember their given names, nor my paternal grandmothers maiden name; they had no role in our lives. There were six children in our family, and we divided into the Four Oldest and the Two Youngest; Stephen and I were the youngest, thrown together by the divisions of age, and we became as close as tree and bark. Our family was Irish and Catholic on both sides, and we carried a full cargo of ethnic and religious freight as it shifted in the long passage between immigration and deracination. There were times in my life when I, unlike Stephen, tried to disavow the Irish and the Catholic, an effort that was always a source of amusement to him. Stephen had perfect pitch for pretension, especially mine, and a cold eye for the warts and wens of social nuance. Until I went away to college, we shared a room at home, and for a period in New York until I got married we shared an apartment.

The last time I saw him, two or three months before he died, he reminded me that when we were children he would often do my crying for me. Our father was a quick man with a strap to enforce discipline; it was a matter of pride with me not to cry. Indeed I would start to giggle when I returned to our room, and Stephen, fearful that my father would give me another taste of the leather, would keen loudly to avert that possibility. We both had a tendency to stammer, and whenever we met, all too rarely the last fifteen years of his life, we would discuss stratagems to avoid the minefields of speech. I used to say howdy because I would stumble on hello, and he would say wee because he would falter on little, and when we compared tactics we would dissolve in laughter, a laughter that only another stammerer could ever understand. From childhood on, Stephen could make me laugh. I remember a golden-haired four-year-old, in a perfect fury at being banished from a family dinner for my sisters violin teacher when there was no room at the table, poking his towhead into the dining room and saying the dirtiest thing he could imagine: Hey, kids, enema tube.

We spoke often on the telephone when my wife and I moved to California, and saw each other whenever we were in the East. He was best man at my wedding and I at his; he was my daughters godfather and I godfather to his eldest son. That wise woman my mother would often tell me that Stephen played life on the dark keys, but I never heard the melody. I did not know that for years there were intermittent bouts of melancholy, dark downward spirals. Once in a while we talked about depression, but in the way one talked about fevers now safely passed, viruses isolated and inoculated against. I called them the jits, head colds of the psyche. We even devised a cure: bed rest, Heath bars and Oreo cookies. The following Christmas Stephens present to me was a perfectly printed five-color photograph of a glass of milk and a stack of Oreos. I was impatient with the emotional extortion of much of what passed for depression. I thought it a bid for attention, a demand for a close-up on the soundstage of life. I had a routine on this sort of theatrics, and the last time I saw Stephen I did my performance and he threw me lines from the wings, and we laughedoh, God, how we laughed. It was not in Stephens nature to do a star turn, to give his melancholy billing. What I saw in Stephen was always the same thing: someone I was always truly happy to see. Sometimes when we were alone we would speculate on which one of the six children would die first. Never Stephen, never I; we always settled on one of the others. And then the telephone rang at 4:30 in the morning. He had gone into his garage and with infinite care taped the doors and windows shut. Then he got into his car, started the engine and asphyxiated himself.

There are things to do when there is a sudden death, and the first thing I did, I did badly. I called one of my two older brothers, a motion picture and television producer, who had come upon bad times of his own, an almost terminal crisis of confidence. He was living in a small cottage in a rural Oregon community, trying to piece his life back together. It took some time to reach himhe had no direct telephoneand when I told him what had happened, there was a cry of such bleakness that I can remember it still. He pulled himself together and said he had been contemplating suicide himself, perhaps even at the exact same moment as Stephen; it was as if the nature of Stephens death had foreclosed an option. It was then I added quite unnecessarily that there was no need for him to go back to the funeralhe had not really known Stephen all that well, I said, Stephen being ten years younger and in any event I could not afford to pay his way east. I blame neither the stress of the situation nor my reaction to it for saying something he quite rightly thought wanton and insensitive. We had not, in fact, got along in years, which was more to the point. The reasons for what at times was a quite active, and often quite poisonous, mutual dislike I think are best attributed to, if I may paraphrase Alexander Pope, that long disease, life. Our war was not so much cold as gelid; in seasons of dtente we were correct. He had gone to Oregon in search of an epiphany, and from there I was the occasional recipient of long, artful letters, full of character evaluation and private secrets and revisionist family history; blame was sprinkled like holy water; the archbishop of this schismatic church was careful to douse himself as well as his congregation of family. I had the uneasy feeling that there was an audience for this exchange of letters to which I was not privy, with the result that my answers became at best perfunctory. Some weeks after Stephen died, my wife read his next letter but I refused; it appeared more or less a compendium of my shortcomings in most of the moral arenas, beginning with my telephone call that terrible morning. I threw it into the fire, unread; fair enough, but instead of letting it go at that, I was impelled to announce I had done so in a brief communique to Oregon, I who had claimed to Stephen, that last time we saw each other, that I had little interest in the theater of my own life, and none whatsoever in the theater of anyone elses; these are the small self-deceptions by which we are defined. Fuck you, came back the immediate and spontaneous reply; my note, he said, had been much discussed at his support group, which at least confirmed my suspicion that ours had not been a private correspondence.