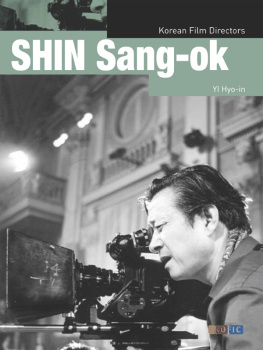

Korean Film Directors

The Korean Film Directors series is one of Korean Film Councils projects to furnish an international audience with insight and analysis into the works of Koreas most representative film directors.

The series aims to expand upon the existing body of knowledge on Korean film, educate the general public of the history of Korean film and Korean film directors, and draw attention to the significance of works that represent Korean film. Critics who share their insight in the series are leaders in their respective specialties. Each volume includes critical commentary on films, an extensive interview with the director, and a comprehensive filmography for reference.

SHIN Sang-ok

Written by YI Hyo-in

Translated by Colin A. Mouat

SHIN Sang-ok

Written by YI Hyo-in

Copyright 2008 by Korean Film Council

All Rights Reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without the written permission of the publisher.

Korean Film Council

206-46 Cheongnyangni-dong, Dongdaemun-gu, Seoul 130-010, Korea

Phone (82-2) 958-7596

Fax (82-2) 958-7590

http://www.kofic.or.kr/english

email:

Published by Seoul Selection

B1 Korean Publishers Association Bldg., 105-2 Sagan-dong, Jongno-gu, Seoul 110-190, Korea

Phone (82-2) 734-9567

Fax (82-2) 734-9562

http://www.seoulselection.com

email:

Preface

When I was young, at a time when we might learn the names of novelists or poets but never that of a film director, the first name I learned may have been that of SHIN Sang-ok. After that, I learned the name of KIM Hyo-cheon (who had the same first name as my older brother), and then I think I came to recognize HA Kil-jong and LEE Chang-ho as directors. And then, after some time, the names of countless Korean and foreign directors came into my head, yet even then SHIN Sang-ok was somehow unfamiliar. The reason for this was that, at the time when I was busily learning the names of directors, SHIN was in North Korea. Political taboos were so rife at the time that I recall lowering my voice a little and looking around me whenever I talked about SHIN Sang-ok with my friends in film. In that way, he came to stay with me as an even more mythical figure. Actually, there was nowhere to see his films at that time, so virtually the only images of him that remained with me were certain scenes from his film Eunuch, which I saw when I was a child, and a few scenes from Red Muffler.

Around the time when I was studying Korean film history and beginning to work as a film critic, I always tended to avoid facing up to the inscrutable figure of SHIN Sang-ok. It may have been because I couldnt re-watch most of the films he had made, and because I wasnt sure how I should look at him following his escape from North Korea. However, at some point I was assessing films made by SHINs teachers and students, and I had the opportunity to see the films he had made in North Korea and just a small portion of the films he had made before being kidnapped. In the process, I think I became able to put forth a provisional assessment on him.

But now, as I put out this book, I have come to think that I should modify the assessment that I made. Not only have I gained a new sense on his cinematic and historical views, but I have also come to the conclusion that it may be possible to view many aspects of Korean film history in a new light or reinterpret them through a study of SHIN Sang-ok. In addition, I tried to avoid viewing SHIN as one director who made certain cinematic texts, since it appeared as though he had made his films while surrounded by a system he had constructed himself. But this does not mean that I want to say that it is not possible to find any personal originality or authorial characteristics, let alone that this book represents some grand discovery or the recounting of something shrouded in secrecy. I have done my utmost to dissolve such feelings and judgments within the words of the book, and I have also come to the conclusion that I should do further research in the future.

This book is made up of the following parts: SHIN Sang-ok, Another History, which falls under the area of a discussion of the director; SHIN Sang-ok and the SHIN Sang-ok System, wherein I attempt to examine SHINs cinematic and social activities from various angles; excerpted portions of interviews conducted by the film researcher LEE Gi-rim for the magazine Cine 21; a personal biography and chronological record of his works; and a list of synopses. As SHIN is no longer with us, no new interview was possible, and after examining several interviews I decided to print LEE Gi-rims, since it seemed the most appropriate for this book. I extend my thanks to her. Also, though I was unable to include it separately, I extend my thanks to EBS producer AHN Tae-geun, who graciously allowed me consult interviews that he had conducted.

July 2008

YI Hyo-in

On the Director

On the Director: Part I

SHIN Sang-ok, Another History

Master

SHIN Sang-ok directed 74 films during the 52 years from his debut with 1952s The Evil Night to his final film, 2004s unreleased A Winter Story. This includes films that he made in North Korea and the United States. This number of works cannot be called very large when viewed against the period of his activity. In comparison with prolific directors like IM Kwon-taek, KIM Soo-yong, or Japans Kinoshita Keisuke, he could be said to have made relatively few films. But the period in which his major works were produced was generally restricted to the 1960s. Also, he is not represented by one sole work, as YU Hyun-mok is with Aimless Bullet (1961) or KIM Ki-young is with The Housemaid (1960). This may be because his major works, while outstanding, do not have that certain clear something that crosses cinema and art history, and it may be because of his tendency toward diverse works that combined films of diverse genres.

KIM Su-nam writes: In 1975, the Japanese film magazine Kinema Junbo selected and printed a list of major foreign directors representing world cinema for its supplementary edition (December, Vol. 21), and SHIN was the only Korean director included on this list of world directors. The cinematic author was introduced in the journal as a director of the social school who frankly portrayed the reality of Korea within various political constraints. It appears that perhaps he was called a social school director in consideration of the revocation of the registration for his film company Shin Films. But if he is referred to as a director from the social school, this ends up offering a somewhat narrow selection or imprecise designation, as he not only made films in various different genres, he also made films with a strong scent of collaboration with national policy.

KIM Su-nam, perhaps finding it difficult to define a director who made films with such diverse inclinations as SHIN Sang-ok with a single word, referred to him as a master of mise-en-scne. It is certainly undeniable that SHINs films had particularly beautiful mise-en-scne in comparison with other Korean films of the time. In his Deaf Samryong-i, the image of Samryong and his masters wife crossing the village where the river flows is reminiscent of Eastern painting, and in the scene of the whole village, captured in a long shot, as Samryong fetches the villages doctor of Korean medicine, the characters movements are comic yet dynamically linked, allowing the audience to be drawn into the urgency of their emotions. An obvious analysis would be that SHIN Sang-ok was familiar with the composition of mise-en-scne because of his history as an art major, but one cannot help noting that he also had his own outstanding sense for connecting the narrative and image. However, in explaining SHIN Sang-ok the director, it would be difficult to reach a consensus on treating mise-en-scne as the most important element. To explain his films, it is also necessary to explain various other elements.