Also by Laurel Holliday

T HE C HILDREN OF C ONFLICT series:

Children in the Holocaust and World War II: Their Secret Diaries

Children of The Troubles: Our Lives in the Crossfire of Northern Ireland

Children of Israel, Children of Palestine: Our Own True Stories

A Washington Square Press Publication of

POCKET BOOKS, a division of Simon & Schuster Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 1999 by Laurel Holliday

Originally published in hardcover in 1999 by Pocket Books

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Pocket Books, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

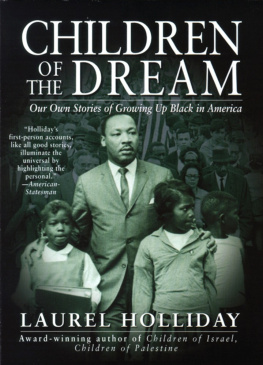

Children of the dream : our own stories of growing up Black in America / [compiled by] Laurel Holliday.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN: 0-671-00806-4

ISBN 978-1-4767-7534-0 (ebook)

1. Afro-AmericansSocial ConditionsAnecdotes. 2. United StatesRace relationsAnecdotes. 3. RacismUnited StatesHistory20th centuryAnecdotes. 4. Afro-AmericansBiographyAnecdotes. I. Holliday, Laurel, 1946EI85.86.C47 1999

973'.0496073'00922dc21

98-50209

CIP

First Washington Square Press trade paperback printing January 2000

WASHINGTON SQUARE PRESS and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster Inc.

Contents

Introduction

Now is the time to make justice a reality for all of Gods children.... I have a dream my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not he judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. I have a dream today!

D R . M ARTIN L UTHER K ING, J R .,

I Have a Dream,

delivered at the March on Washington for Civil Rights, August 28, 1963

I n this, the fourth volume in the international Children of Conflict series, African-Americans from across the United States invite us into their childhoods. Carrying on a long-standing black autobiographical tradition, the thirty-eight writers in this anthology recount the struggles, as well as the joys, of growing up in twentieth-century America, In poignant, personally revealing, and often highly entertaining true stories (nearly all of them published for the first time in this book), they tell us what it was like to grow up stigmatized by the color of their skin, yet often very proud of their heritage, their culture, and their community.

Exploring the roots of their racial awareness, they describe turning points in their youths that changed their lives forever; the shock of the first time a white child called them nigger, the agony of wanting to be friends with a white child but knowing that they werent good enough, the humiliation of being told that they were dirty because they didnt wash their hair every day and that they were ugly because their facial features and skin color were different from the majority.

In one of the stories, a writer describes a group of white adults chanting Two, four, six, eight, we dont want to integrate at her and her black classmates when they were just barely old enough to climb up the steps of their Brooklyn elementary school for the first time. Another writer depicts the utter humiliation and even physical torture he suffered at the hands of racist Los Angeles County sheriffs. Another tells us what it was like to live every day in fear of starvation because welfare did not provide enough food to sustain him and his sixteen brothers and sisters. And yet another describes the anger that rose in him in response to the blatant racism of his elementary school teacheran anger that, when full-blown, would eventually lead to his being incarcerated on death row in San Quentin Federal Penitentiary.

Some of the writers describe the difficulties not of being black and suffering at the hands of white racists, but of being found not black enough by their own peers. To be judged the wrong shade of black by other blacks, they say, or to be found uncool by those of ones own race for not being able to afford the right athletic shoes, is as excruciating, sometimes even more so, than to be bullied by insensitive whites.

Tenderly, yet precisely, these writers point out how blacks perpetuate prejudice by insisting on certain hairstyles and ways of speaking, for example, and by disrespecting those of different educational and economic experience from their own. Several of them describe the double bind of feeling trapped between two colors:

Why did they hate me for being a little different? Sounding educated and being interested in different things than they were didnt make me any less black, did it? It seemed that I was too black for the white people, yet not black enough for the black people.

(Charisse Nesbit)

The early blows to my psyche were not black or white. They were black and white. And I loathed them equally.

(Bernestine Singley)

Ranging in age from eleven to seventy-five and raised in twenty-two states, the writers in this volume provide a wide window on the experience of growing up black in the United States. Born about the same time as Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., one writers coming of age took place in Boston against the backdrop of the Great Depression. Another grew up in the 1950s and writes about her admiration for her father, a famous bootlegger in New Jersey who was proud of being able to support his family without working for white people. Three describe their efforts to integrate previously all-white schools in the 1960s: one in Brooklyn, one in Boston, and one in South Carolina. Three more describe the enormous effort and expense of trying to maintain their hair in a way that would be acceptable to the majority culture and their black peers. And several write about adolescent racial challenges that they are still in the midst of: one in Birmingham, Alabama, and three sisters living in a small town in Georgia.

Polls indicate that the lives of black children have not improved since Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., proclaimed his dream for children in 1963. At that time, one out of five black teens was living below the poverty level, and black teens had the lowest rate of suicide of any teenage racial group in the United States. Now, as we near the turn of the century, one black teen in two is living below the poverty line, and black teen suicide rates surpass those of all other racial groups.

In this book, in the context of the writers own personal experiences, we learn of the persistent racial inequities that black youth have been faced with over the course of this century. At a time in their lives when they might need to simply focus on the ordeal of growing up, they are forced to deal with racism.

But the writers also write about their resilience and how they learned to transmute such injustices into determination to achieve racial justice. As such, the writings here are a testament to the endurance of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.s dream, the courage of black youth and the role of creativity in the redemption of racism.

Even though this anthology spans eight decades and includes a wide range of black experiences from coast to coast, it is not a history book; nor is it a sociological account of African-American childhood and adolescence. What you will find here are the true, intimate, and finely crafted accounts of thirty-eight black peoples coming of age during what, if he had not been assassinated, would most likely have been the lifetime of Dr. King. Most of the writers tell me they have written their stories with a desire to extend racial understanding and to increase, in whatever way they can, racial justice and equality in this country. But they speak for themselves and of themselves; none would presume to speak for all African-Americans. And, similarly, there is no attempt on my part to have this book be representative of the full range of African-American cultures, lifestyles, and experiences in the twentieth century.

Next page