Foreword by Greg Maddux

Back in 1987, I was one of the youngest players in the majors and getting knocked around pretty good my first time through the National League.

It was an exciting and challenging year. I was a 21-year-old kid hoping to prove to myself and everyone else that I could pitch at the major league level. At the same time, I was trying to fit in with my teammates and develop routines that would improve my chances of staying in the big leagues and having a successful career.

Despite going just 614 in 1987, I felt I had made positive strides in these areas.

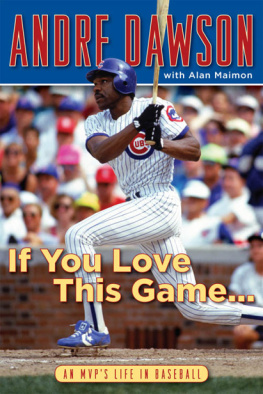

Andre Dawson played a big role in my learning process.

Hawk was a man of few words, so it wasnt anything he said that made an impression on me. It was everything he did.

I spent a lot of time simply observing Andre, who was in his first year with the Cubs that season. I watched how he got ready for games. I watched how he worked out after games. I watched how he handled the media. And until we both signed with other teams after the 1992 season, I never stopped doing those things.

As a young player, you pick guys you want to model your career after. Even though I was a pitcher and he was an outfielder, Hawk became one of those guys for me.

Before I ever met Andre, I respected him. The steps he took to get to the Cubs in 1987 were incredible. Rather than staying with an Expos team that took his services for granted, he accepted a pay cut to play in Chicago. By doing so, he stood up for his principles and to owners who had colluded to keep free agents from signing with other teams.

He then went out and established himself as the best player in the National League that season, winning the 1987 MVP Award.

It was an unusual way to do it, but I hope I conveyed my admiration for Andre in a July 1987 game when I hit a Padres player with a pitch in retaliation for Andre getting beaned earlier in the game. It turned my stomach to see Andre lying on the ground with blood streaming down his face.

Coming into that game, I was 57 and really could have used a victory. We had a three-run lead when I drilled Benito Santiago in the back during the fourth inning. I was ejected before pitching enough innings to qualify for the win. But that was okay. It was one of those times when doing the right thing took precedence over personal gain. I saw the situation as an opportunity to gain Andres and the teams trust.

Despite not saying a whole lot, Andre was very much a team leader. He let his preparation, play, and work ethic do the talking.

Heres what I saw nearly every day during the baseball season for six years:

Before games, Andre would take care of his ailing knees, stretch, take outfield and batting practice, and then have his knees worked on again. Hed play the game, and when it was over, hed take care of his knees again, work out, and then finally, hed talk to the media.

That last part really impressed me. After very long days, he made time for reporters. But by tending to his body first, he sent a message to me that its more important to prepare for tomorrow than it is to talk about what you did today.

There were times when I could see Andre was really hurting, but he still maintained his routine every day.

Andre took pride in his performance and wanted his teammates to do the same. He was almost like a silent coach on the field and in the clubhouse. He wanted guys to do things the right way. And if they were smart, all they needed to do was follow his lead.

We had a lot of fun in the Cubs clubhouse during those years. Away from the cameras, guys messed around with each other and pulled pranks. I was a prankster. Andre wasnt. But that didnt keep him from having a good laugh at some of my antics. He was a serious guy, but he also had a sense of humor.

Early in my career, I learned a lot from my Cubs teammates and coaches. Rick Sutcliffe taught me never to try to embarrass a hitter because that would only give him added incentive to want to hit off me. My pitching coach, Dick Pole, instructed me on the finer points of pitching, including all the mental stuff. Goose Gossage helped me learn not to let emotions get the better of me.

Those were lessons I took out to the mound that helped me become a successful pitcher.

Andres influence on me was different.

Simply put, every day I was around him, he showed me how to play and prepare for the game. And he did that without ever speaking a word.

There were a few times late in my career when I didnt feel motivated to get my work in. Whenever that happened, Id think, Hell, if Hawk did it, I can, too.

Andre and I left the Cubs on the same day in December 1992. I signed with Atlanta, where I spent the next 11 seasons. Andre signed with Boston, where he gave American League pitchers a small taste of what he had been doing for years in the National League. Like Andre, I played most of my career for teams other than the Cubs. But the seasons I played with Andre were ones that helped shape my career.

Hawk was a great player and teammate and very deserving of his place in the Hall of Fame.

7. Among the Best

Following the 1981 season, I finished second to Mike Schmidt of the Phillies in the National League MVP vote and took home a second Gold Glove. During the strike-shortened season, I hit .302 with 24 home runs and 64 RBIs. I learned the Elias Sports Bureau had crunched some numbers and ranked me as the top offensive outfielder in the National League. That was all well and good. I was honored to be recognized for my accomplishments, but at the end of the day, baseball is a team sport. And it nagged at me that I wasnt able to contribute timely hits when we needed them in the 81 playoffs.

As far as I was concerned, the window of opportunity was still wide open for the Expos. The core of the team was still in place. It was just a matter of staying healthy, playing up to our potential, and luring a key free agent or two to cross the border. Our team batting average in 1981 was just .246, so we definitely could have used another hitter.

Making that happen was easier said than done.

The Expos had been trying for years to lure a marquee player. Prior to my rookie season in 1977, Reggie Jackson, a free agent at the time, came to Montreal to discuss signing with the Expos. Reggie hadnt yet achieved Mr. October status then but was considered one of the best power hitters and biggest personalities in the game. The local newspapers ran splashy headlines announcing his visit.

Im not sure Reggie ever had any intention of signing with the Expos, but that didnt stop the organization from rolling out the red carpet and doing everything it could to woo him. And by everything, I mean they offered him a heap of money, something in the neighborhood of $700,000 a year. That was a lot back then even after you factored in the Canadian taxes that the Expos and Blue Jays players had to pay. To put in perspective what Reggie would have earned in Montreal, the three players who ended up playing the outfield for the Expos in 1977Ellis Valentine, Warren Cromartie, and memade $85,000 combined .

Not surprisingly, Reggie signed with the Yankees, where he earned even more money than that and also got the chance to play in the national spotlight. Montreal, after all, wasnt New York City.

Hopeful the team could come away with a big free-agent prize for the 1982 season, I lobbied Expos president and general manager John McHale to bring in an offensive star. The names I suggested were former Expo Ellis Valentine, who had been shipped to the Mets the previous season, and Dave Parker, a former National League MVP who had enjoyed many good years in Pittsburgh. I guess the price for Parker was too high. That was unfortunate because when he landed in Cincinnati a few years later, he put together some of the best seasons of his career. McHale ruled out bringing back Ellis and told the press that he thought I had a soft spot for guys who have been in trouble. There were rumors at the time that Ellis had a drug problem. If that was the case, I felt he could benefit from being back in familiar surroundings with his old friends in Montreal.

Next page