ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Every book including this one is a collaborative effort. Without the support and encouragement of many people, it would have remained a dream.

I want to thank Ethel Parker for her editorial assistance while the manuscript was in its infancy. Sincere thanks to my literary agent, Janell Walden-Agyeman. Janell you believed. The expertise and the warm friendship of my editor, Barbara Quick, was invaluable. Much thanks, Barbara.

I wish to extend my heartfelt appreciation for the encouragement of two Marys. Mary Poplin, my professor at Claremont Graduate School who planted the seedshe knew a book like this was needed. And, my Conari Press executive editor, Mary Jane Ryan, who helped cultivate that seed to its fruition. Mary Jane gave this greenhorn writer not only an opportunity to write, but had the patience, insight, and TLC to guide me along the way. Mary Jane, thanks for helping me unveil the hidden spirit of this work.

I want to thank my family and close friends who have encouraged me from beginning to end. I especially thank my husband, Saul, who kept the house going, while I kept the computer going; my daughter, Donna Key, bless you for being you; my sister-in-law June Zuckerman, supporter extraordinaire, Dr. Dorris Woods, my friend and college colleague; Prissy McClendon, my sister; and my friends Peggy Patterson, Lynne Emile, Annette Shamey, Ariann Swinson, Almeta Washington, and Dr. Michelle Wittig, who were my main cheerleaders.

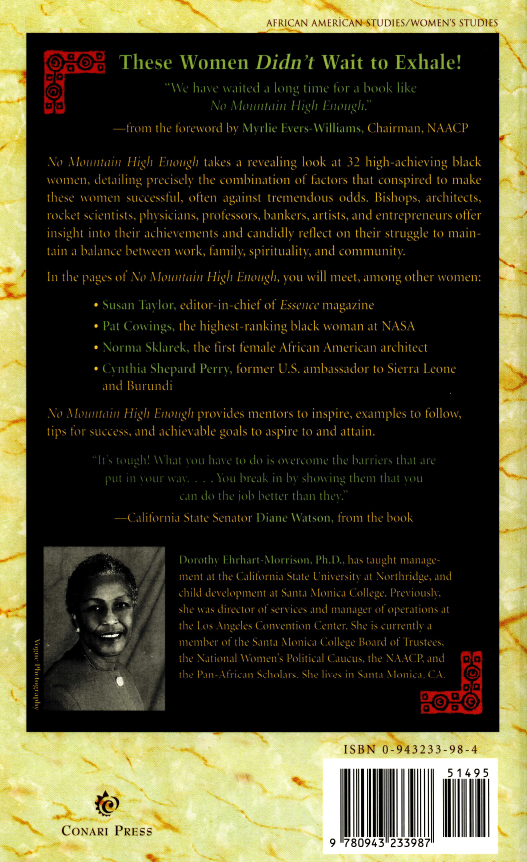

Most of all, I want to thank the thirty-two women who so graciously allowed me to enter their lives and stay awhile.

c onari Press, established in 1987, publishes books on topics ranging from spirituality and women's history to sexuality and personal growth. Our main goal is to publish quality books that will make a difference in people's livesboth how we feel about ourselves and how we relate to one another.

Our readers are our most important resource, and we value your input, suggestions, and ideas. We'd love to hear from youafter all, we are publishing books for you!

For a complete catalog or to get on our mailing list, please contact us at:

CONARI PRESS

2550 Ninth Street, Suite 101, Berkeley, California 94710

800-685-9595 Fax 510-649-7190 e-mail

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Angelou, M. Wouldn't Take Nothing For My Journey Now. New York: Random House, 1993.

Baurind, D. Socialization and Instrumental Competence in Young Children. In W. W. Hartup, ed. Research on Young Children. Washington D.C.,: National Association for the Education of Young Children, 1972.

Bethune, M.M. Address at Texas Southern University, June 1950. Paraphrased quote taken from Life and Times of Frederick Douglass. London: Collier-MacMillan LTD (1962): 508. Revised edition of 1892.

Coles, R. Children of Crisis: A Study of Courage and Fear. New York: Dell Publishing Co, 1968.

David, J., ed.. Growing Up Black. New York: Avon, 1992.

Ellison, R. from Gross, S.L. & Hardy, J.E., eds., Images of the Negro in American Literature, 21. Chicago & London: University of Chicago Press, 1966.

____. Black Families in White America Andrew Billingley. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1968, 3.

Greenfield, E. Bubbles. Washington, D.C.: Drum and Spear, 1972.

____. Rosa Parks. New York: Crowell, 1973.

____. Nathaniel Talking. New York: Black Butterfly, 1989.

Johnson, C.S. Shadow of the Plantation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1934.

Johnson, J. E. The Negro Problem. New York: H. W. Wilson, 1921. An article by William Seneca Sutton in University of Texas Bulletin, No. 221:24. March 1, 1912.

Lerner, G., ed. Black Women in White America: A Documentary History New York: Vintage Books, NY.

____. Langston Hughes' poem, Mother to Son. In Jim Crow and Jane Crow by Pauli Murray, 593.

Little, L. Children of Long Ago. New York: Philomel Books, 1988.

Mitchell, E. P., ed. Those Preaching Women vol.1. Valleyforge: Judson Press, 1985.

____. Those Preaching Women vol. 2. Valleyforge: Judson Press, 1985.

____. To Preach or Not to Preach. Valleyforge: Judson Press, 1991.

Owen, D., New Yorker magazine article, January 30, 1995.

Pauli, H. Her Name Was Sojourner Truth. New York: Appleton, Century-Crofts, 1962.

Ratcliffe, D. Women EntrepreneursNetworking & Potato Pie. Los Angeles: Corita Communications, Inc, 1987.

Taylor, S. L. In the Spirit: The Inspirational Writings of Susan L. Taylor. New York: Amistad, 1993

____. In the Living. New York: Anchor Books, 1995.

Wood, P. H. Black Majority. New York: W. W. Norton and Company, Inc., 1974.

Wright, M. in Black Women in White America: A Documentary History. Gerda Lerner, ed. New York: Vintage Books.

CHAPTER 1

THE BLACK FAMILY

My father insisted that his children learn a skill and spendtime on a job, but we could choose [which] jobBecause my father was in the auto repair business, those were the skills I was [first] taught. My brothers and I used [our mechanics'] skills and knowledge to earn money, frequently earning a dollar or so to jump-start cars and charge batteries for our neighbors JENNIFER LAWSON

J ENNIFER LAWSON exudes both energy and competence. Executive I vice president for national programming and promotions at Public Broadcasting Services, she was responsible for selecting, distributing, and promoting a full schedule of television programsfrom Sesame Street to the MacNeil-Lehrer News Hourfor the 340 member stations across the country. Like every other woman profiled in this book, Jennifer Lawson is an African American.

Lawson is the granddaughter, on her father's side, of slaves. Both parents were born in the South, her father in Bullock County, an agricultural region of Alabama, and her mother in Louisville, Kentucky. Her parents met and married in Birmingham, Alabama, where Jennifer was born. Lawson's mother attended Alabama State University, after which she taught school. As a young man, Lawson's father worked as a coal miner, and then as a steelworker in the Birmingham mills. He was later the proprietor of an auto repair business and a respected member of the community.

Jennifer Lawson credits her parents for setting her on the path that led her from Birmingham to Tuskegee Institute, where she was awarded a full academic scholarship, to her active involvement in the civil rights movement, her work as a field representative for the National Council of Negro Women, to Tanzania in East Africa, where she lived for two years, to Columbia University, where she earned her master's degree in fine arts, and finally to the corporate offices of PBS. I had a dose relationship with my parents, and each in his or her own way was a positive influence in my life. My mother was a real caring and compassionate person, Lawson recalled. My obligation to care for and be aware of the feelings and pain of others came from my mother. [She also passed on to me] her love for books and the acquisition of knowledge.

My father, on the other hand, encouraged me to do whatever interested me. He was a very creative person, an inventor. His only requirement was that I tackle my goals seriously. If I wanted to be a ballet dancer, I had to be willing to study and rehearse long hours. He helped me to understand the amount of work and hardship that is necessary for success. He taught me mechanical skills along with my brothers, including how to rewire electrical motors and generators. Because of her father's encouragement, Lawson developed self-confidenceand the unspoken awareness that gender, for her, would be no barrier to success.

Next page