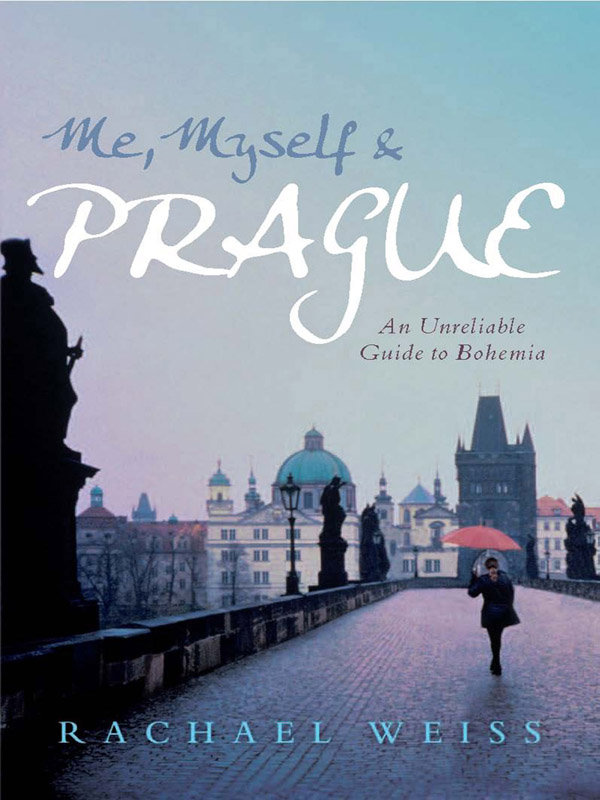

Rachael Weiss currently lives in Prague where she is technically the in-house writer for a hotel but, since the only thing she has to write is the website and occasional stiff letters to defaulting customers, in reality shes the odd-jobs girl. She supplements her income by writing horoscopes for a series of obscure suburban and specialist papers and thus feels justified in describing herself as a syndicated columnist. Rachaels greatest achievement to date is a fourth place in the New South Wales scrabble tournament. One day she hopes to master Czech scrabble. She is the author of Are We There Yet (Allen & Unwin 2005) and is currently working on her third book.

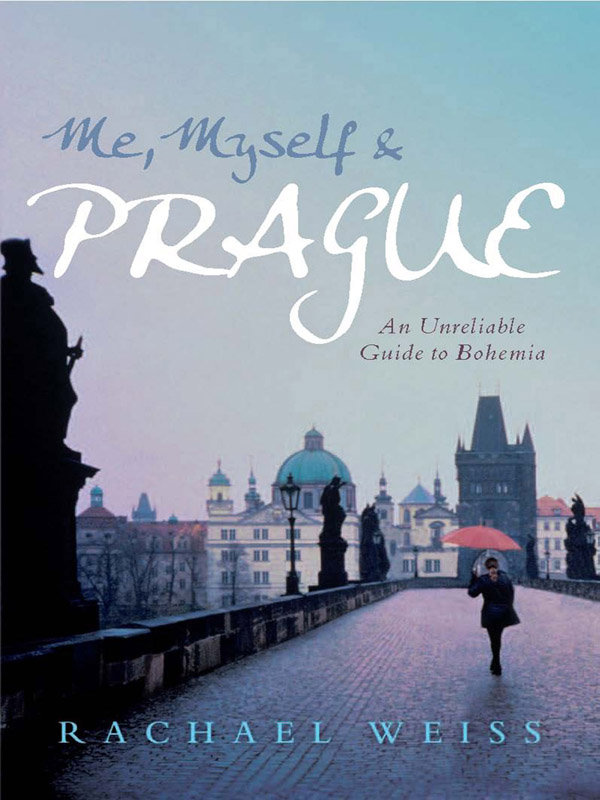

Me, Myself &

PRAGUE

An unreliable

guide to Bohemia

RACHAEL WEISS

First published in 2008

Copyright Rachael Weiss 2008

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Fax: (61 2) 9906 2218

Email: info@allenandunwin.com

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

Weiss, Rachael, 1964 .

Me, myself & Prague : an unreliable guide to bohemia.

ISBN 978 1 7411 4820 6 (pbk.)

1. Travel - Voyages and travels - Humor. 2. Prague

(Czech Republic) - Description and travel.

910.4

Typeset in Australia by Bookhouse, Sydney.

Printed in Australia by McPhersons Printing Group, Maryborough.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For my father

Zdenk Weiss

and my grandparents

Karel Weiss and Bohumila Weissov

Contents

A t thirty-nine I took stock of my life. I am the eldest of three, with one sister and one brother. My sister is a fitness instructor, has her own dental practice and is the mother of two perfect children. My brother is a lawyer, a partner in his firm, and the father of three perfect children. Both are energetic and rich; they are a source of pride and joy to my parents. I, too, was once a source of pride and joy to my parents. I was six.

The school principal had just told my parents that tests revealed I was a gifted child. It seemed like a good thing at the time. They boasted of it to all their friends. They gazed on me with satisfied eyes; theyd known all along I was someone special and now tests, scientists, people who knew these things, had proved it. My whole world looked down on me and said, Now our friends have no choice but to believe itwe got the best baby. Shortly after this event my parents divorced, bitterly.

My brother and sister, not gifted, managed to live through the turmoil and come out the other end moderately normal. I, gifted, did not. School, university and life seemed too much for me to comprehend, to the disappointment of my parents. They still told all their friends I was giftedeveryone hung on to that one with increasing obstinacybut my giftedness never manifested itself again. Subsequent primary and high school tests relegated me to the B stream, my mothers lips pursing at each fresh new evidence of the teachers blindness and incompetence. My giftedness came for one test when I was six, then left. Such is life.

Adulthood saw no improvement. Boyfriend after useless, bottle-wielding, unemployed boyfriend came and went, the average length of each relationship about six and a half months, unless he was married, in which case the affair dragged on for years. And I seemed unable to grasp the nature of working life. I got a lucky break straight after university where, by the simple method of choosing English as a majorsince the one thing I do seem to be fitted for is reading and English required nothing more of me than thatId managed to pass. I was hired by a company of management consultants, but corporate life shredded me.

All around me thin women in spiky suits and beefy, rowing-blue men celebrated their successes in topless bars and roared and flourished. I gazed helplessly at company reports and market analyses and thought: Surely this is all a crock? A giant con? These people seemed to have invented a raft of meaningless jargon and strung it together to sound important. But I was the only one who thought so. Everyone else seemed endlessly enthusiastic. The company gave me less and less work until I fell on my own sword and resigned.

After that I had several stabs at corporate life, since that seemed to be what a white, educated, middle-class woman was supposed to do, but I failed every time. My God, those people are toughthey ate me alive. At every defeat I blamed myself: What was wrong with me? Why couldnt I make a career? In my heart of hearts I really wanted to be a writer, but I felt that that was a frivolous, self-indulgent desire, so I suppressed it, never thinking that this might be what was wrong.

My parents were less concerned about my career and more concerned about my inability to fulfil the other tasks of the white, educated, middle-class womangetting married and having childrenalthough they each had different ways of expressing their dissatisfaction. My mother referred to me almost exclusively as Poor Rachael and sighed a lot, but my father was more proactive, chivvying me to get on with it: A woman is a hunter, darling.

My relationship with my parents had settled into this state of affectionate despair after many years of difficulty. Six years after my parents had divorced, we children had been taken away from our father for good. It was a long and ghastly separation process, but by the time I was twelve it was completewe no longer saw Dad on the weekends. It wasnt until I was twenty-eight (possibly in preparation for turning thirty, although I cant remember now) that I had gone looking for him. When Dad and I finally met up again it had been awkward at firstwhat do you say to a father you barely recognise? The most difficult part had been the first few months when we were ever so polite to each other. We were both relieved when, almost a year after we became re-acquainted, we had our first fight and our relationship began to feel more normal. I still enjoy the times we get snippy with each otherthey seem more precious to me even than the love.

My relationship with my mother, however, swung the other way. We developed a friendly, but distant, relationship. She did not take well to my reconnection with my father. I think she feared she would lose me and up to a point she was right. As I saw more of him, I saw less of her. I guess I figured shed had my sole attention from when I was twelve to twenty-eight, so now it was his turn. I saw my father and my stepmother every Friday night, making up for lost time.

So this, then, was my situation at thirty-nine: I didnt have a career or goals or partner or dependents, or even white goods, but I had a few close friends and two loving, if disappointed, parents. The sum of my life seemed to me to be a pretty small thing; a life lived mostly in fear of doing what I wanted and trying to be good in the eyes of others. And then, out of the blue, a miracle happened. A publishing company put out a small book Id written about two single women on a road trip. For the first time in my life an organisation devoted to profit thought I might be of use to them. More, they thought I might be of use to them as a writer. The words Seize the Day kept coming to me.

Next page